Ask a curator: What's Yiwarra Kuju?

A Q&A with John Carty, anthropologist and co-curator of our new exhibition, Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route.

John is currently Research Associate at the Research School of Humanities and the Arts, Australian National University. He was kind enough to talk to us about Yiwarra Kuju, providing us with some fascinating insights into an already fascinating exhibition.

Q: What is this exhibition about?

John: At first glance, you’d assume the exhibition is about the Canning Stock Route, an 1800 kilometre droving track that ran through the heart of Western Australia and was created to provide another avenue for bringing cattle from the north to the south of the state.

But the stock route, the way it was made, and its impact on desert waters and people, has had a complicated legacy for desert people to this day.

As surveyor, Canning’s job was to find water at regular intervals – a days walk apart – to bore wells for the cattle to drink from. To do this, he needed Aboriginal guides. Some were willing helpers, but several of these guides were used against their will.

The manner in which the water was located and secured for white colonial commerce cast a shadow longer and wider than the route itself. It is one that people express in their art today. While none of the artists in this exhibition were alive in 1906 when Canning first went through, most of them grew up in the desert watching these strange white men and their cattle passing through their Country.

Yiwarra Kuju tries to show that Aboriginal beliefs and values are not as mysterious or far removed from the average punter as they are often portrayed. We want to move people beyond the notion that Aboriginal Country is just landscape. And to give them an intimate understanding of Country – of the waterholes that people paint, as ‘home’, as a part of themselves.

Yiwarra Kuju means ‘one road’ in the Martu language. We’ve used ‘one road’ to bind the art, people and story of the Western Desert together. We use the Canning Stock Route as the meeting point, as the cross-cultural scaffolding on which to develop an understanding of Aboriginal Country, and the shared history that happened within it.

Q: What can visitors expect when they enter?

John: A visually stunning, and technologically pioneering exhibition. It is not what you would expect of a fine art show, and it’s probably not what people would expect of a museum show either.

We make paintings the visual stars, but not at the expense of story. The two go together, they need each other. If anything, it is a museum show wrapped in a fine art show. And it is driven at every point by the voices of the Aboriginal artists and professionals involved in the project.

Q: What do you hope visitors take away from the exhibition?

John: Visitors, regardless of their levels of understanding of Australian History, Aboriginal art or Aboriginal Culture, can expect to be surprised, entertained by the playful and interactive qualities of the show, but also, we hope, a little challenged.

It’s a great entry point for tourists, or people visiting Australia, as it provides an introduction to Aboriginal Culture, Aboriginal Art and Australian History all in one.

It’s also wonderful show for kids, and families, because we’ve created some pioneering technology (basically a 10 meter long IPAD touch-screen which allows kids to explore their interests, or just play, in their own way), which captivates younger audiences in ways that basic social histories rarely do.

It's an exhibition for people who think they know nothing about Aboriginal art. Unlike so many exhibitions in fine art galleries, it invites you in and gives you a range of different ways of learning how to see and read these paintings.

That said, it is also an exhibition for people who think they know a lot about Aboriginal art, and particularly desert art. Yiwarra Kuju, because we took the importance of Country so seriously in curating the show, challenges a lot of the tired platitudes and preconceptions that govern the display of Aboriginal art at the moment.

Q: What are some of the highlights in your opinion?

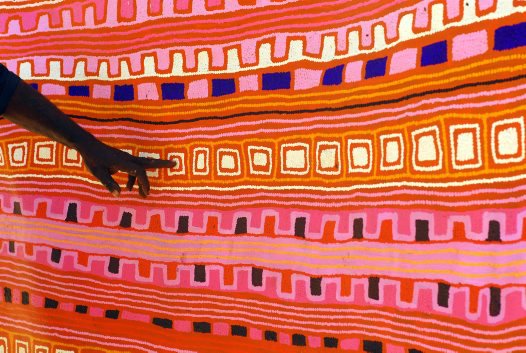

John: Obviously the touch screen technology I mentioned before is a huge highlight of the exhibition, but my personal highlight is probably Patrick Tjungurrayi’s big pink painting, Canning Stock Route Country.

It might not be the best painting in the show, everyone has their tastes, but for me it is without doubt the most interesting work of art. During the research for the Canning Stock Route project, Patrick accompanied this painting, as he was painting it, with a series of oral histories that illuminate his Country and artistry in revelatory ways.

The top line of white squares is actually the Canning Stock Route, the bottom line is the Dreaming. As he unfolded this line out into the painting, he also unpacked his memory as we were driving through the desert rolling and unrolling it each day and painting it at different sites along the Canning Stock Route during the project.

Most people don't paint these great dreaming narratives over vast distances. Most people don't document multiple historical events in one painting and most people don't feel authorised to paint this much. However, everyone paints combinations of this kind of content when they paint their Country, because the dreaming is inseparable from the land, from family, from history and the currents of your own life.

© Tim Acker, FORM

Q: How did this exhibition come to be?

John: It began with a series of workshops run through the FORM Canning Stock Route project, the principal expression of which was the enormous Return to Country trip we undertook in 2007.

On this trip we sought to invert the processes of history by bringing all the artists and storytellers who had left that Country back to the Canning Stock Route to tell their stories. We travelled along the Route for a month or so, visiting sites, and recording Aboriginal oral histories of that Country. And at various places we would stop for a few days and the artists for that Country would paint.

As this process unfolded, we realised that people were painting far more than just a history of the stock route from an Aboriginal perspective, they were offering a radically different perspective on history itself.

So when we translated and transcribed all the stories, and connected them to the paintings that had been produced, it was clear we weren’t telling an Aboriginal history of the stock route, but a bigger story about the Country, about family and Dreaming and the world the stock route cut across.

I think it was around late 2008 when the National Museum of Australia decided that the collection might need a bigger audience too. Through the vision of people like Mike Pickering, they acquired it. But we still had to find a way to structure the story, to anchor all that complexity into an experience that audiences could relate to. We spent a couple of years working through this curatorial problem with our cross-cultural team.

The logic of the show will change slightly in different venues, but the main objective was to create an experience so that when you’re inside the exhibition, you are walking around inside the country. You start in the southern end of the stock route, and wend your way north up the Kimberley, passing through people’s country and the history that unfolded there. History happens where it happens.

© Tim Acker, FORM

Q: You have worked extensively throughout the Western Desert and Kimberleys – what drew you to this area?

John: I was drawn to work in the desert initially by the same kinds feelings that underscore this exhibition. There was a story out there, a story in which I was implicated just by being Australian, a story that I knew nothing about.

It’s ridiculous; I somehow managed to get a degree in Anthropology without knowing anything about the people of my home Country. I wanted to know more, I wanted to find a way in to understanding the people of this country, their story of Australia, but I guess like many people I didn’t know where to begin.

I think its a really common feeling – particularly among older generations who never had access to Aboriginal history in school. Art was my window, my way in.

So I set out to write my PhD on the Balgo artists, many of whom are represented in the Yiwarra Kuju exhibition. I spent three years living in Balgo learning about what it is that people paint, but more importantly learning about the people who are doing the painting.

That work in Balgo, and my familiarity with desert artists and languages, lead to my involvement in the FORM Canning Stock Route project. Tim Acker and Carly Davenport were developing the project in 2006, and asked me if I’d come along the stock route for a month or so to record the artists stories and make cups of tea.

A few weeks ago I was in Perth for the opening there, where all the CHOGM delegates got to see the show, and I was still fetching cups of tea. Nothing much has changed, except that now, there’s an exhibition travelling around the Country that tells an important story, an exhibition I can take my kids to and know that they won’t grow up ignorant in the same way I did.