When photography came to the Museum

© Australian Museum

This article first appeared in Explore, Autumn 2019 issue. Click here to view the full magazine.

The invention of photography in the 19th century was an international sensation. Announced at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in 1839, the new technology had the miraculous ability to capture light on glass and to provide, for the first time, an unmediated, mechanical representation of nature and the world. The possibilities – for memorialisation, for documentation, for art and for science – were endless. Photography quickly became a mass medium, and the promise of new optical realism changed the way Victorians saw the world. Within a decade, photography had reached Australia and become part of the way colonial Australians imagined, portrayed and viewed themselves, their homes, their landscape and their lives.

Capturing Nature is inspired by a unique record of early Australian science: the first photographs taken at the Australian Museum. Numbering more than 2500, the collection ranges from the first tentative experiments in the early 1860s to the time when photography was becoming an indispensable part of museum practice in the early 1890s. Beautiful, haunting and sometimes strange, this unique collection is little known outside the Museum and has never been revealed to the public before.

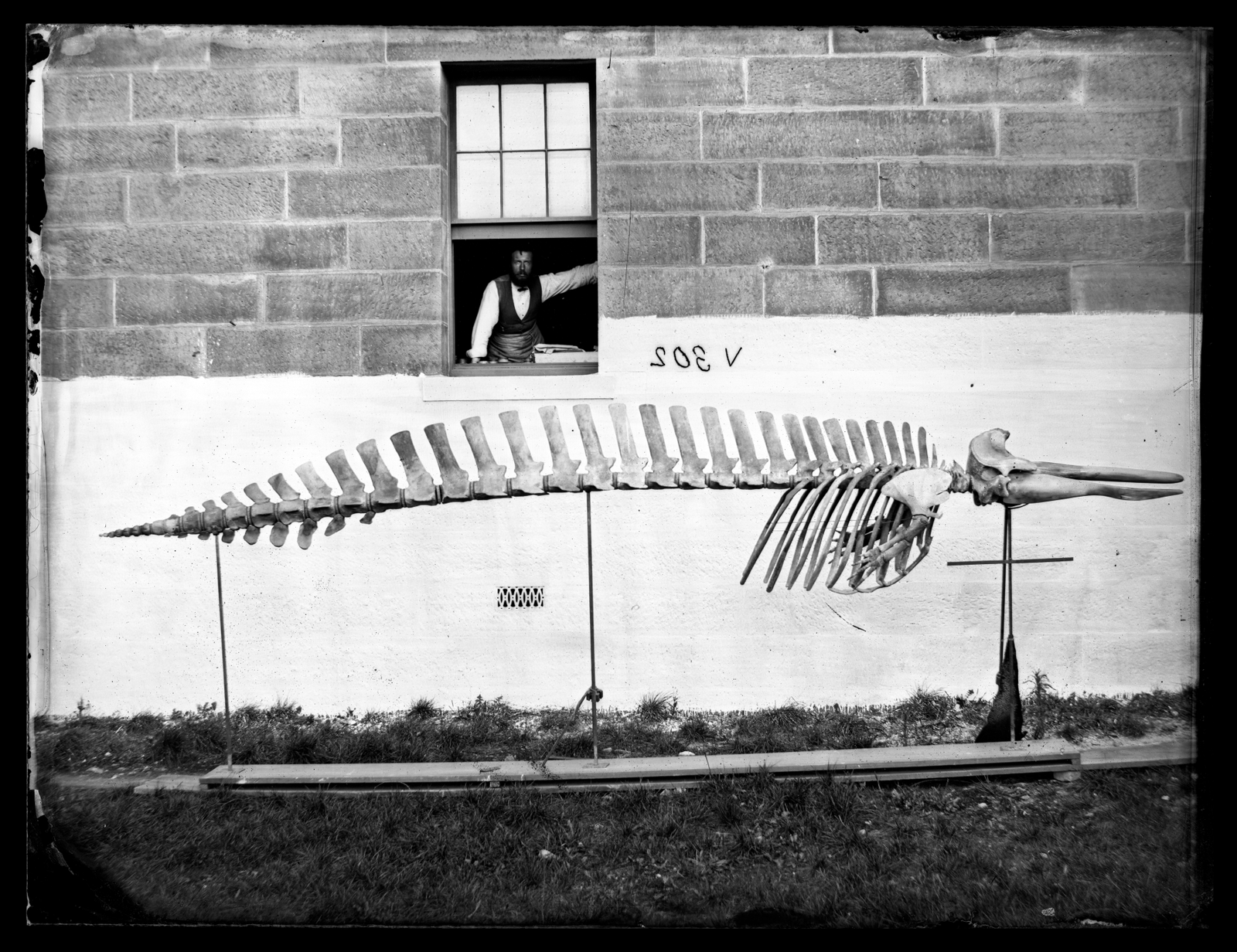

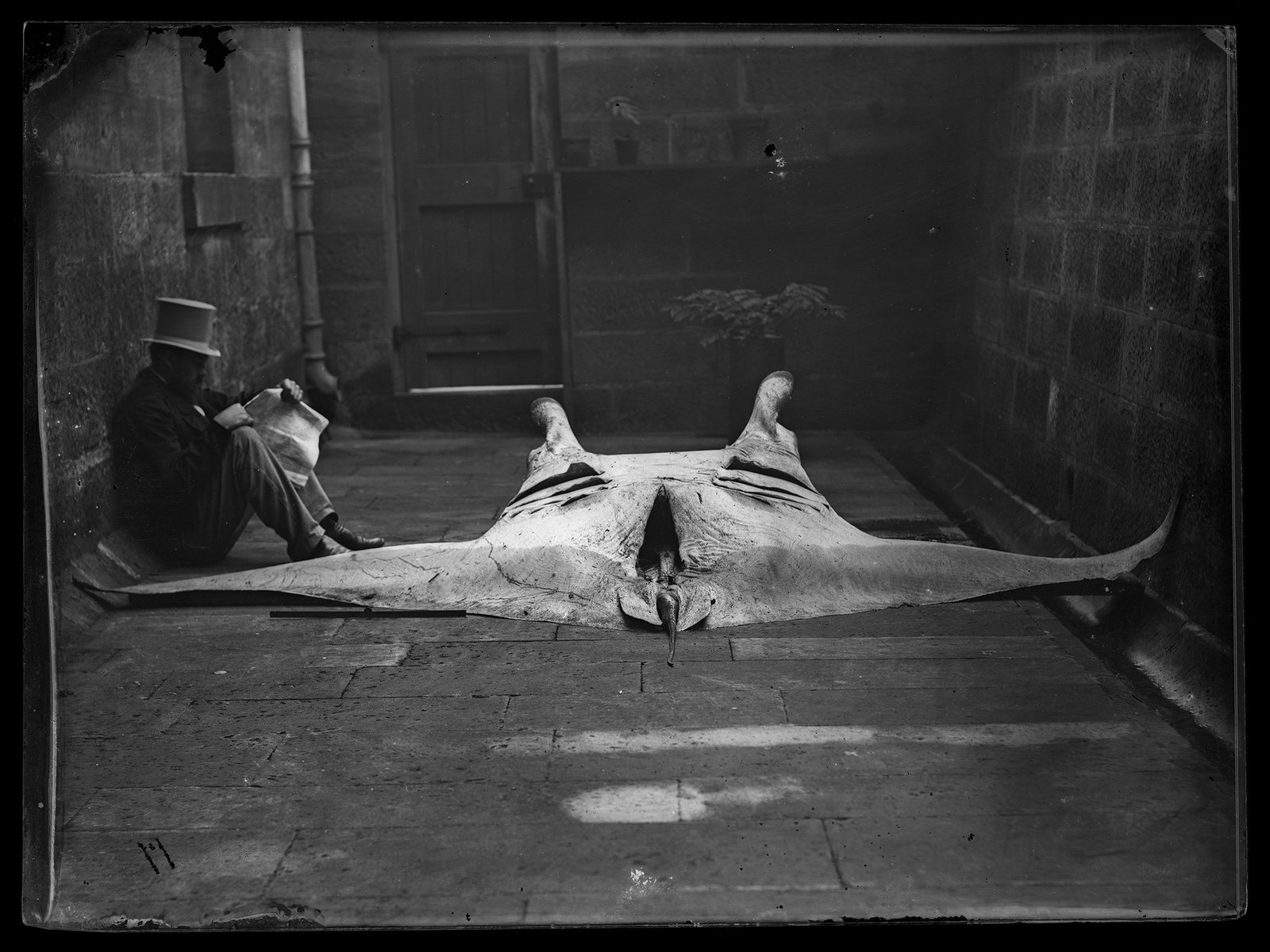

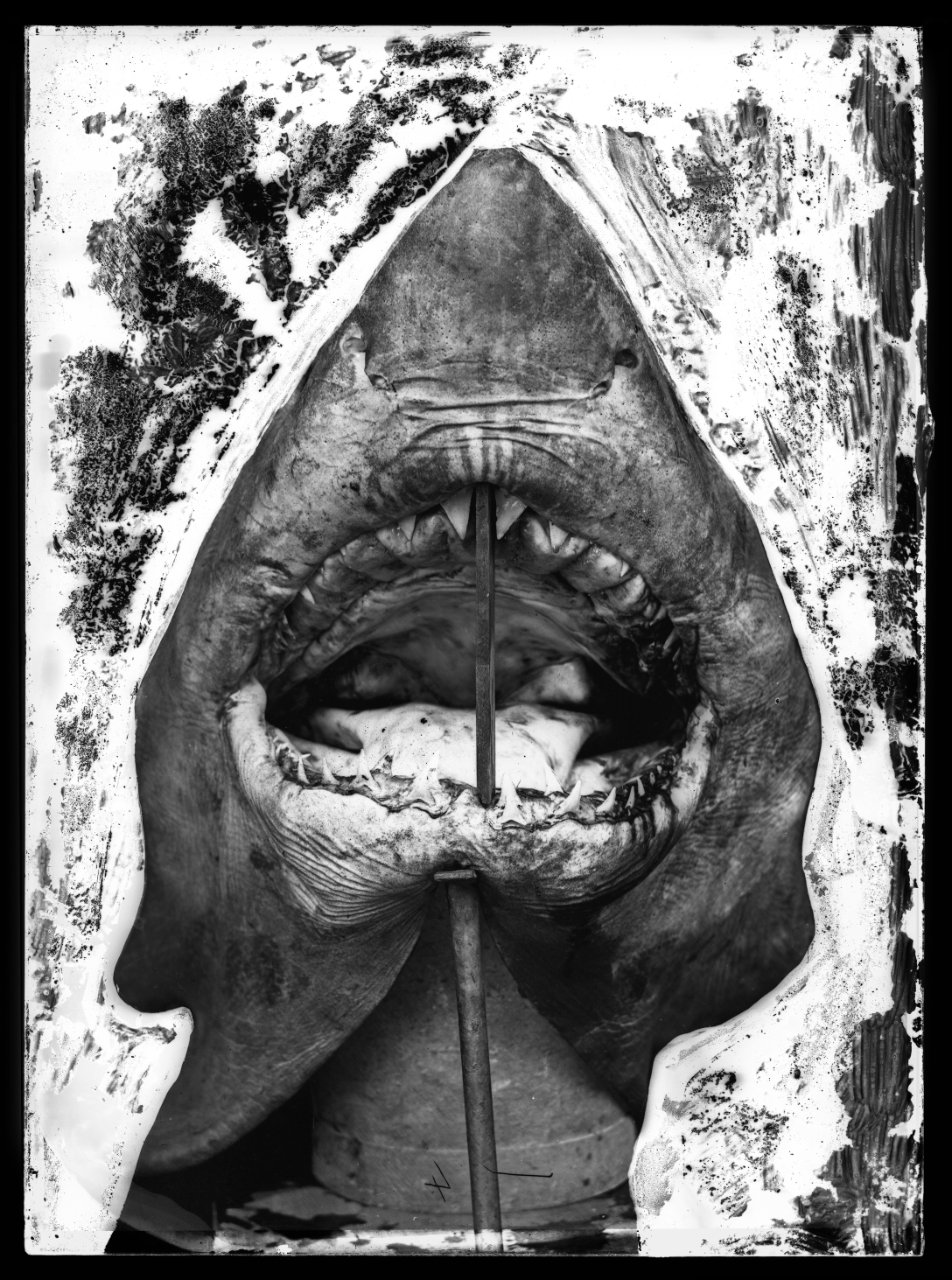

Held in the Museum’s archives, the photographs document the rapid expansion of the Museum’s specimen collections in the second half of the 19th century. It’s a natural history rogues’ gallery: dozens of animals captured, mugshot style, against a white-sheet backdrop. The photos were taken in and around the Museum, mostly in the courtyards and gardens to best exploit the precious light required by the photographers’ rudimentary cameras. The exhibition features 67 large-scale images, with almost 100 more featured in the companion book. The subjects vary from a large sunfish and the flipper of a Sperm Whale to a gorilla and the fragile bones of a flamingo. Alongside the animals, the photographers sometimes documented themselves – holding a specimen or posed next to a manta ray for scale. The images they left behind are a window straight into their world.

Alongside the photographs, the exhibition features a selection of the original specimens captured on glass more than 150 years ago. The display of early photographic equipment and taxidermy tools illustrates the painstaking processes of preparing the specimens and making the photographic glass plates. And for the first time, the Museum’s fragile, earliest photographic albums are on display.

Photography could record specimens as they arrived at the Museum, capturing true-to-life texture, size and shapes before the detailed work of taxidermy began.

© Australian Museum

Making a modern museum

For the Australian Museum, the 1860s marked a lucky confluence of skills, experience, need and technology. In 1864 – after several years as assistant and acting curator – Gerard Krefft was officially appointed to the top job, museum curator, a position he held for 10 years. Krefft had encountered photography as a member of the 1856–1857 Blandowski expedition through Victoria along the Lower Murray and Darling Rivers. His new position at the Australian Museum allowed him the time to fully explore the medium and its possibilities.

Photography had arrived in the colony of New South Wales in the early 1840s, but for its first two decades was mostly commercial. For both photographer and subject, the process was arduous. Cameras were heavy and expensive; exposures were long. For the general public, the arrival of the new carte de visite format in 1859 – a small calling card featuring the sitter’s portrait – was wildly popular and, worldwide, cartes were taken and swapped in the millions. For scientists, photography offered a tantalising glimpse into the unseen-photographs could potentially reveal details that were too fast, too small or too far away for the naked eye to see. In Europe at this time it was scientists who were making some of the earliest photographic experiments.

At the Australian Museum, photos quickly became crucial. They could record specimens as they arrived, capturing true-to-life texture, size and shapes before the detailed work of taxidermy began. In the field, they recorded landscapes and people. And they recorded the Museum as it was – the early pictures of galleries, workshops and buildings are the first glimpses we have of the Museum’s daily work. The charm of the photos is in their human scale; these images acknowledge the human in scientific photography, rather than concealing it. Happily for us, as well as documenting spaces and an expanding collection, the photographs contain rich incidental details of time, place and people. Each picture tells a story and reveals the mark of its makers – sometimes literally: a thumbprint on a glass plate; a pair of legs revealed by a blowing sheet strung up as a backdrop.

© Australian Museum

In introducing photography into Museum practice, Krefft had the practical support of museum assistant Henry Barnes, who was able to turn his hand and eye as easily and confidently to the intricacies of taxidermy and articulation (the process of cleaning and assembling an animal skeleton) as to the complicated new techniques of photography. Both men were unafraid of failure, and they took to photography as they had to the other skills they needed to become competent field and museum naturalists – developing expertise through experimentation, trial and error, and learning by doing. The thousands of plates they produced over the 15 years they worked together represent not just an index of the Museum’s specimens, but also a new visual language for natural history. The introduction of photography at the Museum in the early 1860s was the beginning of an experiment that would change the institution.

Outside the Museum, the images were a shorthand way to communicate the institution’s scientific status and progress. Disseminated to Krefft’s networks of mentors, collaborators and peers in scientific institutions in Europe, they also served to announce Krefft’s discoveries, and constituted an important part of his self-expression as a “man of science”. Photography also served as a means of informing peers of findings without having to relinquish the collection, as had previously been the case. Instead of sending precious specimens to Europe for description, Krefft could now take photographs of his discoveries and send those instead. Within the Museum, the photographs were not for display but rather were circulated among staff and Trustees and kept as documentation of the ephemeral details of fresh specimens as they were prepared for the storehouses or for exhibition. Placed into a series of photographic albums, the prints were also important for collection management, control and comparison.

© Australian Museum

Nature on glass

In photography’s first decades, processes were complicated and error-prone; chemical recipes hard to replicate; papers brittle and unreliable; and the sunlight that was so essential to the photographs difficult to regulate and control. Images printed on paper were sometimes fleeting, and when chemically unstable, quickly faded. But the negatives Krefft and Barnes created on cut sheets of handmade glass were robust, sharp and enduring. New high-resolution digital scans and the large-scale reproductions made for Capturing Nature have revealed some of this detail for the first time.

Of course, taking these photographs was not as easy as point-and-shoot. Imagine the challenges faced by these early photographers. Beyond the bloody, painstaking process of preparing dead animals and bones for display in the hot Sydney sun with buckets, tubs and a basic tubs and a basic set of tool – hammers, chisels, files and drills – they faced the added technical difficulties of capturing their images one by one using the slow, cumbersome technique of collodion wet plate photography. Glass plates first had to be prepared by coating them with liquid collodion and silver nitrate in a series of chemical baths. Time was of the essence as the plates had to be used quickly before the chemical balance was lost. They were carefully slid into the camera one by one. The glass plates were exposed to light by simply removing the lens cap – this was a process of trial and error depending on the time of day, availability of light and sensitivity of the chemicals. The exposed plate then had to be taken to the dark room for development in further chemical baths. To make a print, the finished glass plate was sandwiched into a frame with albumenised paper and exposed to light, next to a window or outdoors. Every step required skill, ingenuity, patience and the coordination of many participants, as revealed by the shadowy figures who sometimes appear as blurred, ghostly presences in the photographs.

Initially, photography was the initiative of Museum staff, who mostly covered expenses themselves and used their own equipment and chemicals. The Museum’s conservative trustees were suspicious of these first photographic experiments, and less than eager to embrace photography’s potential for efficiencies, outreach and the global circulation of scientific knowledge. They agreed to the purchase of a new lens for Krefft to take to Wellington Caves in 1869, but the Museum did not pay for its first camera until 1881, when then curator Edward Ramsay insisted they purchase his entire personal photographic kit. The first dedicated photographic studio was built in 1893.

© Australian Museum

The legacy of the photography

The collection and the story of early photography at the Museum are haunted by Gerard Krefft’s untimely fate, a story with a climax that unfolds partly through his photographic work. A coming clash between the new breed of museum worker exemplified by Krefft and the progressive scientific ethos that he championed, and the natural history establishment exemplified by a certain set of the museum’s trustees, was perhaps inevitable. Krefft would prove a visible and somewhat tragic casualty. He lost the job he loved after only 10 years. The unfair treatment of Krefft and his personal tragedy of stubborn misunderstanding casts a shadow over his photographic collaboration with Henry Barnes, and in hindsight make these images especially poignant.

Capturing Nature is about the making of the modern museum – and the part played by the creation, reproduction, use and distribution of information and iconography through photographic images. And it is about the content of those images, representing some of the untold stories from the Museum’s early productive years of systematic collection, display and public access to its natural history and cultural holdings.

The story of the images’ creation represents a wonderfully expressive moment in the formation of Australian scientific identity. Captured in the photographs they took, it is also the story of Krefft and Barnes, as together they experimented with the new science of photography, identifying and refining its ongoing purpose at the Australian Museum.

Like the preparation techniques of taxidermy and articulation that shape, groom and present specimens, photography remains an important part of the of the work of natural history museums. For the first time, Capturing Nature reverses the lens, picturing the museum through its own historical photography collections.

Visit Capturing Nature before it closes on 21 July.

© Australian Museum