When an ancient amphibian fossil met a 12-year-old Palaeo-fan

Arenaerpeton supinatus was a predatory amphibian that lived over 240 million years ago – the fossil of which was found whilst building a retaining wall in 1996. A few months later, this impressive fossil inspired me, a budding 12-year-old palaeontologist. I now work at the Australian Museum and have formally described the species!

In October 1996, landscaper David King was building a garden retaining wall at the home of Mihail Mihailidis on the Central Coast of New South Wales, with rocks obtained from Kincumber Quarry. At the end of the job, David hosed the dirt off the freshly laid stones, and as he cleaned off the top layer, was astonished to find a 240-million-year-old fossil appear from under the dirt.

© UNSW Sydney

David alerted Mihail, who contacted the Australian Museum for the first time about the fossil in early 1997. It was observed by Australian-based palaeontologists Dr Alex Ritchie, Dr Anne Warren and Robert Jones, as well as Canadian palaeontologist Dr Stephen Godfrey, who happened to be working on the Dinosaur World Tour exhibition stop in Sydney at the time. Dr Warren identified the fossil as belonging to a temnospondyl, a group of extinct amphibians which look a little like a cross between a crocodile and a giant salamander.

© Jose Vitor Silva

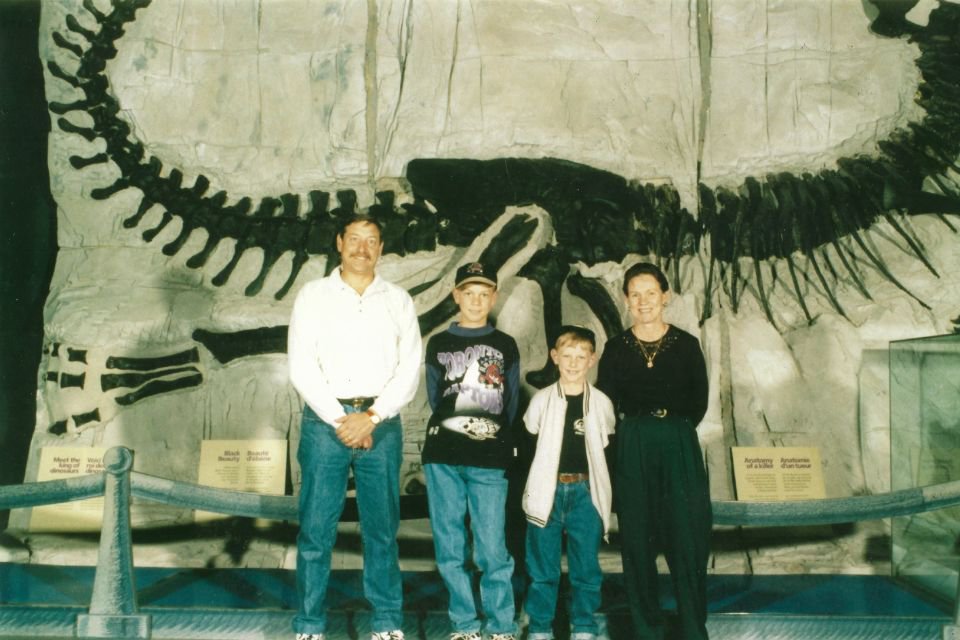

Such was the excitement about the fossil (it caused quite a media stir!) that Dr Godfrey agreed to temporarily include it in the Dinosaur World Tour exhibition for the Australian public to see for the first time. It was then that I, as 12-year-old palaeontology-obsessed kid, saw it for the first time too. Mihail generously donated the fossil to the Australian Museum in 2000, where it has been carefully stored waiting for a researcher with the time and expertise required to accurately describe it. 20 years after the donation, I was offered the job of working with this fossil as part of my PhD, an opportunity I took with both hands. The description has recently been published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

© Lachlan Hart

The fossil is undeniably remarkable. It not only has the skull of the animal still attached to the skeleton, but it also contains the impressions of the animal’s soft tissue (skin) around the body. The skeleton is only missing the tail and back legs, but is preserved “belly up”, so we can’t see features of the top of the skull, such as sutures between bones and eye sockets, which are usually very helpful in identifying species.

After comparing it to many other temnospondyl amphibians, I discovered that it was indeed a new genus and species, which I have named Arenaerpeton supinatus (pronounced Ah-ree-nah-er-pet-on / soo-pin-ah-tus). “Arena” means “sand”, and “erpeton” means “thing that creeps” in Latin. This is a reference to the sandstone block in which it lies, and the fact that it was an amphibian that was probably doing its fair share of creeping around. “Supinatus” translates to “supine”, or “lying on its back”, which is how the animal is preserved. So, the name therefore means “supine sand creeper”.

Through studying Arenaerpeton I have learnt a tremendous amount about temnospondyl amphibians. Temnospondyls are an important case study in the fossil record, as they survived two of Earth’s “Big 5” mass extinction events, including the “Great Dying” at the end of the Permian period which wiped out over 80% of all living things. Arenaerpeton belongs to a group of temnospondyls called chigutisaurids, which also contains the last-ever temnospondyl, Koolasuchus cleelandi from Victoria. Koolasuchus was enormous, perhaps up to 5 metres long. Arenaerpeton, while not so big (probably about 1.2 – 1.5 metres long) was still quite large for its time, as other chigutisaurids that lived during the early-middle part of the Triassic period were smaller. This shows that this amazing group of survivors was already starting to evolve into large sizes not long after the most catastrophic extinction event in Earth’s history.

Arenaerpeton supinatus is a key part of Australia’s fossil heritage. Not only is it a unique fossil with incredible preservation, that adds a vital data point in understanding the evolution of vertebrates in Australia, but it also holds a treasured place in the memories of many who would recall its discovery. This is highlighted by my own personal connection with this fossil, from seeing it as a child to being lucky enough to work on it for my PhD.

Perhaps one day another kid like me will see it at the Australian Museum and be as inspired as I was.

© UNSW Sydney

Lachlan Hart, Technical Officer, Palaeontology, Australian Museum; and PhD Candidate, UNSW.

More information:

- Hart, L. J., Gee, B. M., Smith, P. M., & McCurry, M. R. (2023). A new chigutisaurid (Brachyopoidea, Temnospondyli) with soft tissue preservation from the Triassic Sydney Basin, New South Wales, Australia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, e2232829.

- Scientists name new species of giant amphibian found in retaining wall. (2023). Australian Museum media release.

- 240 million-year-old fossil identified as amphibian Arenaerpeton Supinatus. (2023). ABC News.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge and thank David and Lynda King, the Mihailidis family and Michael Norman (Kincumber Quarry).