Yellow coffin from Akhmim

A mummy, well wrapped in bandages in a painted coffin without a lid from Thebes in Egypt, was gifted to the Museum in 1912 by brewer, politician, and philanthropist, Robert Lucas-Tooth (1844-1915).

Through the style of the coffin, the mummy was attributed to the 26th Dynasty (664-525 BCE), although later radiocarbon dating of a linen sample, indicates the 22nd Dynasty (945–720 BCE). Subsequent examination revealed numerous interesting facts about the mummy and ultimately the coffin itself.

An analysis into the remains indicated that the mummy is probably a middle-aged woman. Major organs were removed, and chest and abdomen filled with an inorganic matter, possibly clay. Fragile but intact bones of the nasal bridge indicate the brain was not removed in the typical way via the nasal passage. There is evidence of early arthritis in the hips, knees, and ankles and an incomplete set of teeth, afflicted by infection. There are no signs that during her life the woman performed heavy physical labour. Both arms are individually wrapped, and the entire body is enveloped in many metres of linen. The coffin, however, was not systematically examined.

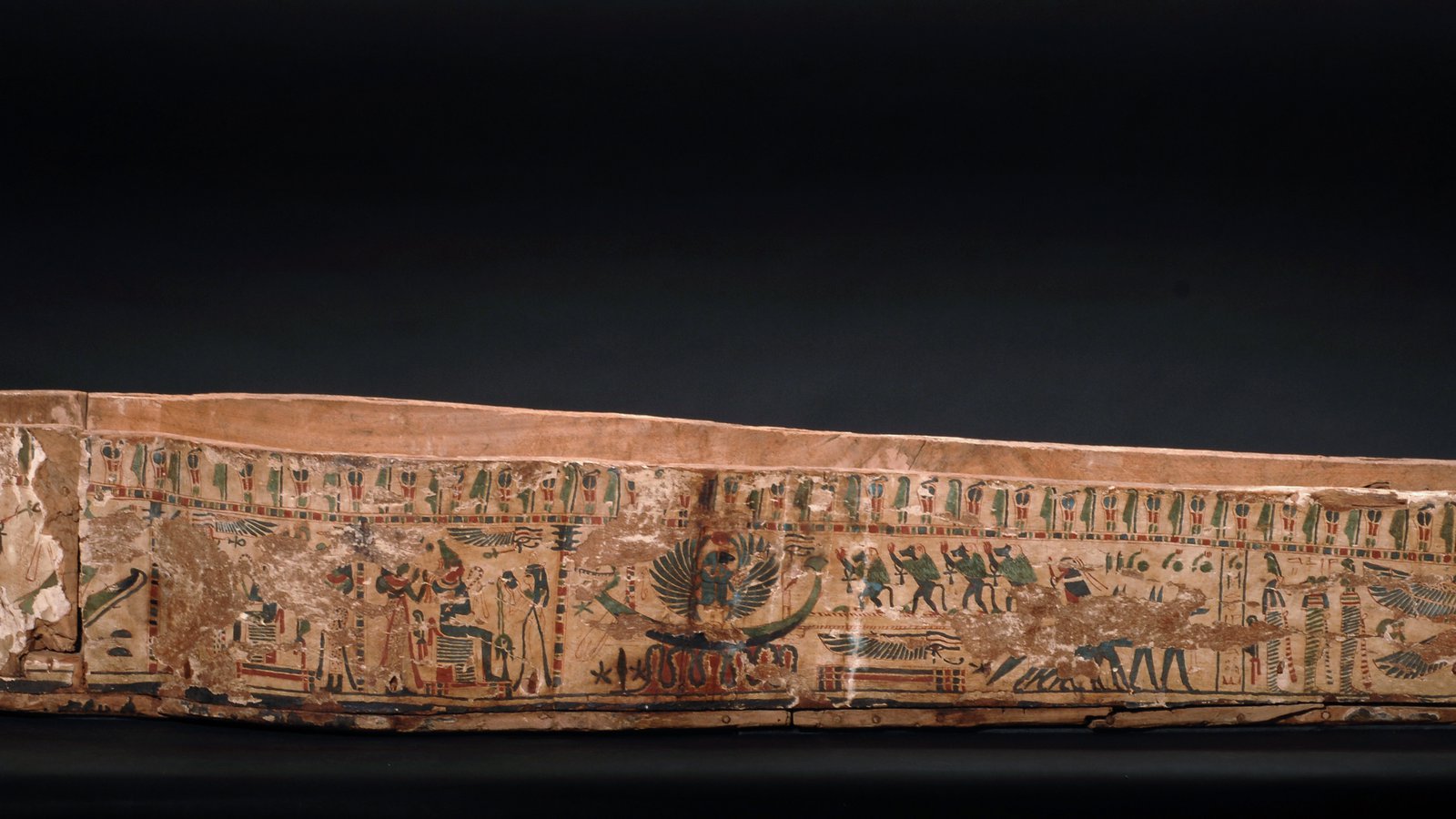

Akhmim mummy in coffin (E19466) - height 32 cm; length 194 cm; width 52 cm.

Image: Carl Bento© Australian Museum

For the period marked by the decline of the New Kingdom (c. 1069 BCE) and the First Persian Invasion (525 BCE), cemeteries at Thebes provide the best evidence of burial practices, their dating, and accessories with a variety of organic materials.

A credible theory suggests that the economic, political, and social strife of the period resulted in the elevation of Thebes as an alternative centre of power, claimed by the priesthood of Amun, who became the de facto rulers of the Upper Egypt. Concurrently, burial practices for elites shifted from building elaborate tombs into making intricately carved and painted coffins. Known as the ‘yellow’ coffin style, it become one of the longest-used types in Egyptian history, with its origin probably rooted in the later part of the 18th Dynasty (Bettum 2012:17-118; Johnston 2022:9-11).

The coffins from Theban cemeteries, well provenanced and dated, attracted the attention of researchers, and permitted the development of typology and a model of coffin evolution. However, many coffins of the period are from different regional areas, usually poorly documented or unprovenanced and scattered through museums around the world. The large number of coffins that originated outside Thebes cannot be accommodated in the Theban model thus explaining their variations and idiosyncrasies.

Dr. Kea Johnston, in her inspiring dissertation, set out to understand the development of coffin styles produced at the workshops at Akhmim, an important regional centre of coffins created in this period, some 200 km along the river Nile north of Thebes.

The coffins of the late pharaonic period from Akhmim have long been neglected as they mostly lack archaeological context or even basic provenance. They were considered provincial and of lower quality. Yet, the Akhmim artists and scribes who produced the coffins developed their own independent stylistic traditions and some of the best examples compare favourably with the coffins from the southern capital of Thebes.

As Dr. Johnston sums up in her paper: ‘The Akhmim artists and scribes produced lively, creative works which would ensure the proper passage of their patrons into the afterlife.’ She demonstrated that Akhmim artists developed their iconographic and religious narrative in broader Ptolemaic tradition ‘through the addition, subtraction, and substitution of elements in a scene’.

The fact that many Egyptian artefacts were purchased by collectors in Cairo and Luxor, having travelled through networks of dealers who kept poor records means that any documentation linking an object to Akhmim is rare.

Consequently, any attribution to Akhmim must be inferred from the physical properties of the coffin itself, supplemented by the titles of the owner, the stylistic variation and quality of craftwork.

Some researchers proposed that the low quality yellow coffins produced in Akhmim workshops in the 21st dynasty (1069-945 BCE), were based loosely on Theban or Deir el-Medina models (Liptay 2011; Niwiński 2017). Dr. Johnston approached this comparison in a more systematic and detailed way. She examined the texts and vignettes, the handwork of individual artists and scribes, finding that they can be distinguished within these workshops. Developing typology based on small variations in vignettes and text rather than large changes in overall layout, she grouped the coffins that seem to be made by the same artisans and scribes, with impressive insight into peculiarity and individuality of each coffin.

She constructed the identification framework based on two groups of provenanced coffins - through names and titles of mummified persons, and documentary evidence. Three coffins in the first group (Hory, Khui-ipuy and Knumensanapehsu) were designated as workshop 1, and one coffin (Aaefenhor) in the second group designated as workshop 2. Careful analysis of paintings, their arrangements, themes, and individual characteristics of script (including consistent spelling mistakes) enabled her to attribute the decoration of these coffins to a team of artists and scribes in each group.

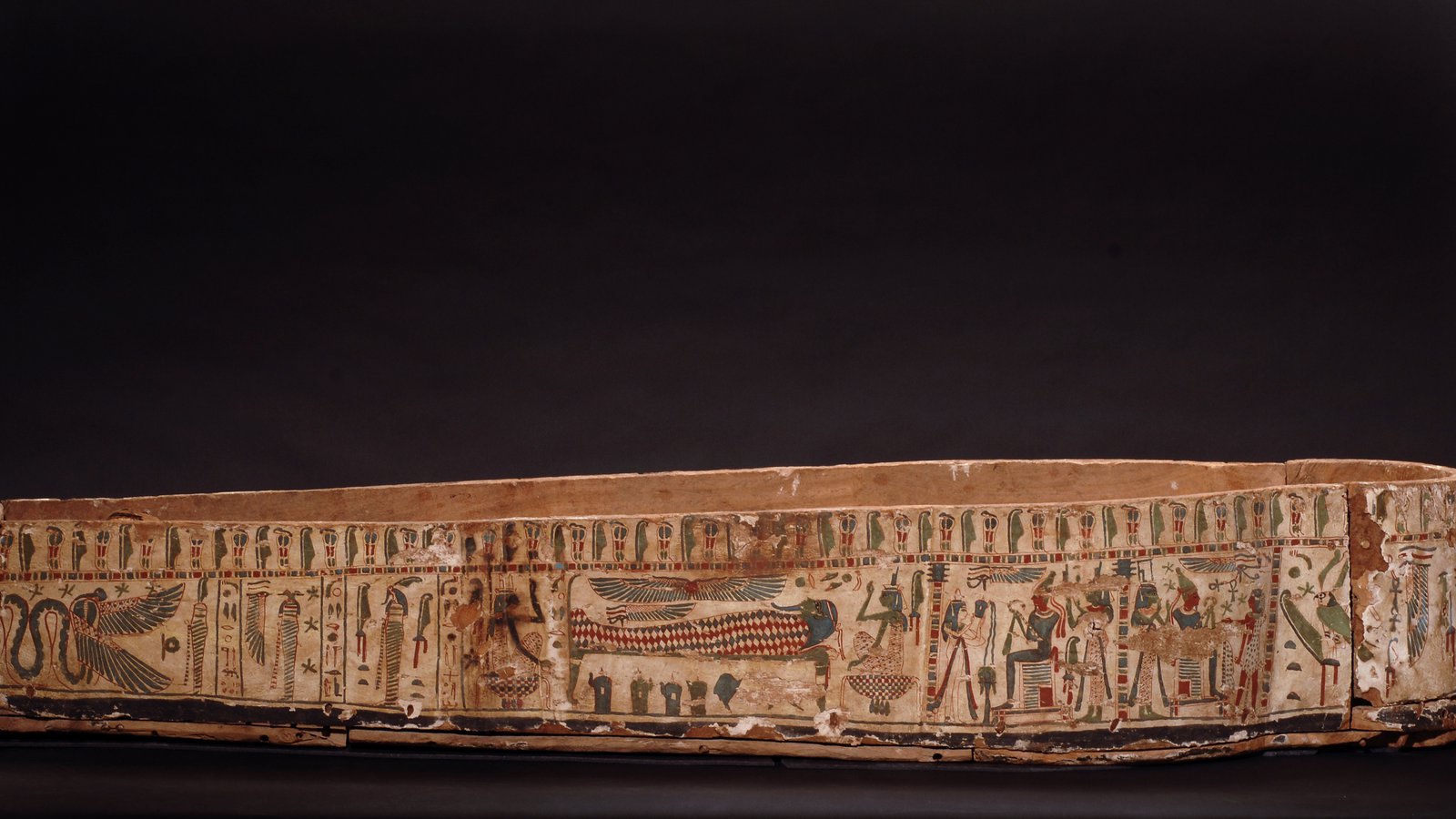

So, how is the coffin donated to the Australian Museum by Lucas-Tooth linked to these groups? The comparison is somewhat limited as our coffin has no lid. This is where the inscribed identity of the mummified person would usually be placed. Detailed analysis of paintings on Aaefenhor’s coffin basin – workshop 2 - and the AM coffin basin is revealing, and it can be summarised in the following points.

The selection of vignettes and their placement is nearly the same on both coffins. The draftsmanship has the same "sketchy" quality as well, complete with blots, smudges, and corrections. The artist apparently still had problems controlling the ink flow and consistency. The same orthographic and ‘spelling peculiarities occur, including the distinctive Nephthys emblem.’ ‘Osiris is drawn in the same posture … and with the same ribbon on his crown … the jackals pulling the sun-barque have the same distinctive profile.’ Dr. Johnston concludes that our coffin was produced at Akhmim during the 21st dynasty, as it was painted and inscribed by the same artist/scribe as the reliably provenanced coffin of Aaefenhor from Akhmim.

While the coffins from Akhmim share a yellow ground, varnish, colour palette, and general layout with contemporary yellow coffins from Thebes, Memphis and other places, they show distinct differences in ‘what is depicted, how it is depicted, and where.’ Essentially the iconography narrates the relationship between the deceased and the trio Osiris, Isis, and Horus. ‘The theme of the selected vignettes centres [on] the relationship between the deceased and the trinity of Osiris, Isis, and Horus.’

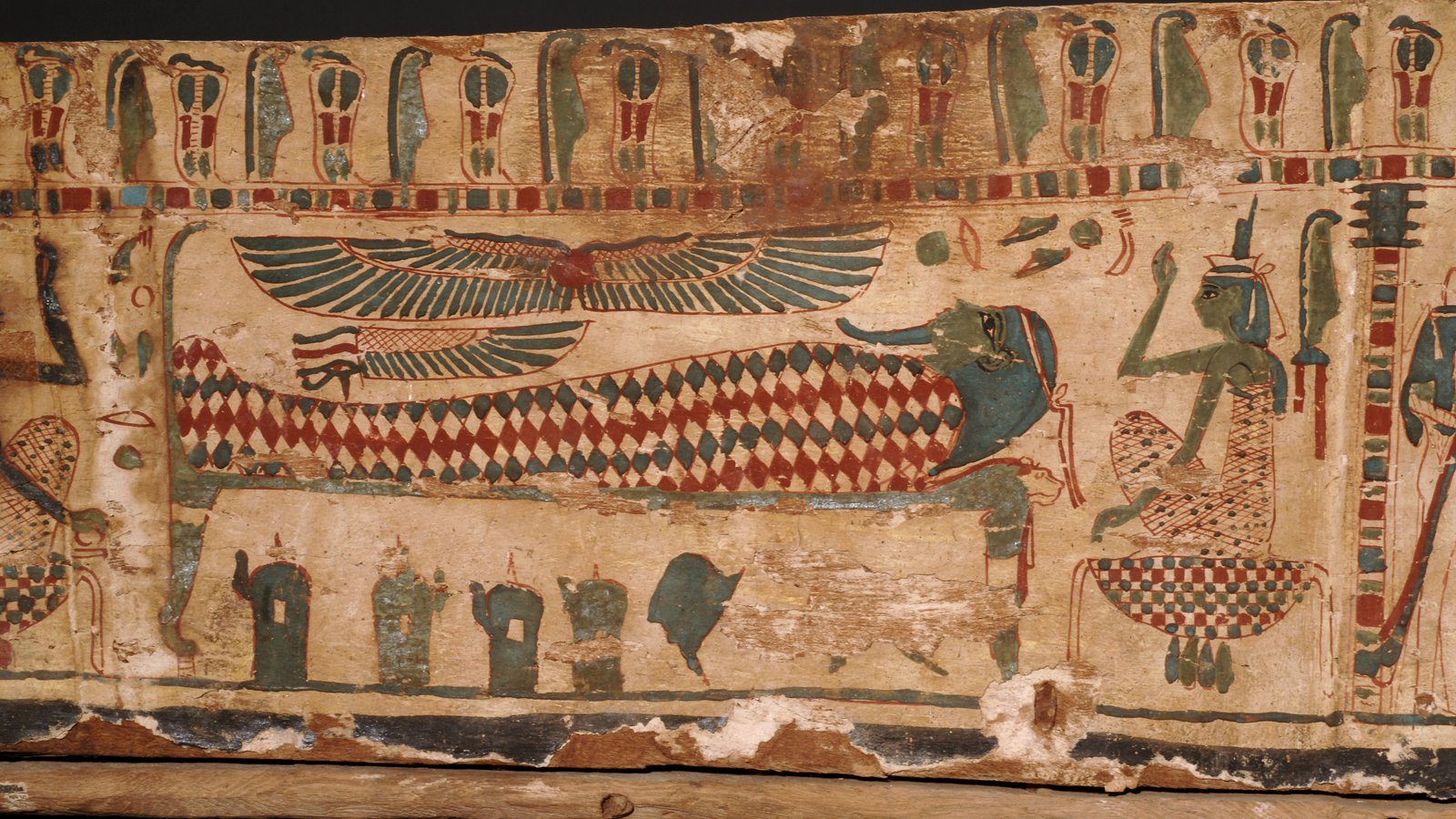

The difference between the 1st and 2nd Akhmim workshops is well illustrated through the “embalming” scene on the coffin basins. In the coffins from the 1st workshop, Anubis is depicted in different variants and composition, and goes about his embalming work of the deceased resting on a bier. The equivalent scene on the Australian Museum coffin departs from this standard. Anubis is replaced by a winged sun-disk. The bier has an added lion’s head and a long tail. The deceased's wrappings are depicted in a diamond pattern. Canopic jars below are given crowns. This scene is no longer a mummification scene at all but ‘through a combination of experimentation and creativity, has become a depiction of the merging of the sun with Osiris in the underworld.’ This creative departure from the norm, among other clues, lead Dr. Johnston to conclude that the artist was not a naïve replicator restricted by his technical skills and knowledge, but to the contrary, able, and confident to reintroduce another narrative and was therefore fully competent in religious and sacred interpretation.

I hope this selective summary about the origin, production and meaning of the yellow coffin at the Australian Museum will encourage our visitors to consult Dr Johnston’s inspiring thesis, which will be published next year (see abstract).

Notes:

All quotes are from Johnston’s Thesis 2022.

Prepared by Ourania Mihas, David Chan, Peter Dadswell and Stan Florek.

References:

- Andres Bettum 2012. Faces within Faces: The Symbolic Function of Nested Yellow Coffins in Ancient Egypt. PhD Thesis, Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo.

- Kea M. Johnston. 2022. Unseen Hands: Coffin Production at Akhmim, Dynasties 21-30. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

- Éva Liptay, 2011. Coffins and Coffin Fragments of the Third Intermediate Period, Catalogues of the Egyptian Collection, 1 (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2011).

- Andrzej Niwiński, 2017. ‘The 21st Dynasty Coffins of a Non-Theban Origin, a “Family” for the Vatican Coffin of Anet’ in The First Vatican Coffin Conference 19-22 June 2013, Proceedings published in 2017 pp: 335-348