Yellow-bellied Sea Snake

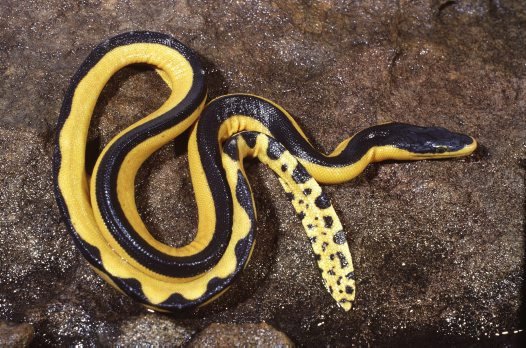

This species is unlikely to be confused with any other sea snake, due to its highly unique appearance.

Introduction

The Yellow-bellied Sea Snake has the distinction of being the most widely ranging snake in the world, as well as the most aquatic, never having to set scale on land or sea floor its entire pelagic life.

Identification

A moderately-built sea snake, with an elongated head distinct from the body. The upper half of the body is black to dark blueish-brown in colour, and sharply delineated from the yellowish lower half. The tail is paddle-shaped and yellow with dark spots or bars. Body scales are small, smooth and hexagonal in shape; the head scales are large and regular. The large eye has a blueish-black iris.

Midbody scales in 47-69 rows, ventrals 264-406.

Habitat

The Yellow-bellied Sea Snake is the most pelagic of all the sea snakes, occurring in the open ocean well away from coasts and reefs. A small individual (total length = 230mm) found in a mangrove swamp suggests that the species may occasionally occur in inter-tidal habitats.

Distribution

Yellow-bellied Sea Snakes are widespread in the tropical parts of the Pacific and Indian Oceans between the 18-20º C isotherms. Currents occasionally carry the snakes into temperate waters, but these are almost certainly far from their breeding and feeding waters. In the western Pacific, the species has been found as far north as Possiet Bay (= Zaliv Pos’yeta), Russia (latitude = 42º 39’ N) and as far south as Tasmania and the coast just south of Wellington in New Zealand (latitude = c. 41º 18’ S). In the eastern Pacific, the species has been found as far north as San Clemente, California (latitude = 33º 35’ N).

In New South Wales, the species occurs occasionally as both living and dead strandings all along the east coast. These strandings have often coincided with either strong onshore winds or storms.

The residency status of Yellow-bellied Sea Snakes along the New South Wales coast is unclear. The vast majority of sightings have been of specimens in poor condition, most likely carried down passively by currents from warmer waters. However, the observation in earlier times of individuals in Port Jackson and gravid females in Botany Bay suggests that they may be, or at least might have been, resident.

Biomaps map of Yellow-bellied Sea Snake specimens in the Australian Museum collection. http://www.biomaps.net.au/biomaps2/mapam.jsp?cqn=Pelamis%20platurus&cql=sn&csy=Square

Feeding and diet

In the wild, the Yellow-bellied Sea Snake eats only fish. It hunts by stealthily approaching its prey or by waiting motionless at the surface and ambushing fish that come to shelter underneath it (small fish are often attracted to inanimate objects such as floating debris). With its mouth agape the snake makes a rapid sideways swipe to snare any fish that comes too close. This snake can even ambush small fish behind its head by smoothly swimming backwards so that the prey then comes within range of its mouth.

In captivity, the snake will feed on whole fish (both alive and dead) or pieces of fish, and may also accept frogs (although frogs would not have been in the diet of this lineage of snakes for possibly several million years). When feeding, the snakes will lunge and bite at anything, including other snakes in the tank, and is known to stick its head out of water to take prey dangled above it.

Other behaviours and adaptations

Yellow-bellied Sea Snakes swim by lateral undulation of the body, and can move both forwards and backwards. They are capable of bursts of speed of up to 1m/sec when diving, fleeing and feeding. When swimming rapidly, they sometime carry their head out of water. On land however the snakes are unable to stay upright and move effectively because their compressed shape makes them roll onto their side.

In the open ocean, Yellow-bellied Sea Snakes often occur in large numbers in association with long lines of debris. These “slicks” form in calm seas and consist variously of debris, foam and scum brought together by converging water currents. In some areas, such as the Gulf of Panama in the eastern Pacific Ocean, the slicks can vary in width from 1 to 300m and stretch for many kilometres. Several thousand snakes may be associated with a single slick. It is not clear whether the snakes actively swim to the slicks or whether they are carried into them passively. Snakes in these slicks have been observed feeding; however mating behavior in these large aggregations has not been recorded.

Being a pelagic species the Yellow-bellied Sea Snake has limited access to hard objects, such as coral, to rub against when the skin is due to be shed. Instead the snake uses a knotting behavior whereby it coils and twists upon itself, sometimes for hours on end, to loosen the old skin. The skin is shed frequently, and in captivity may be sloughed as often as every 2 to 3 weeks. The knotting behaviour also helps to detach organisms such as algae and barnacles that adhere to the skin.

Breeding behaviours

Breeding probably occurs throughout the year in warmer seas but may be restricted to the warmer months in cooler waters. In Australia, gravid females have been found washed onto Sydney beaches in winter (June-July). In the southwest Indian Ocean, females with small developing embryos have been found in late winter and females with near-term embryos have been found in early spring and mid-autumn. Females reach sexual maturity at a snout-vent length of at least 623mm.

From observations in captivity, gestation has been inferred to last at least five months. The female gives birth to between 2 and 6 young, measuring around 250mm in total length. The young are born with substantial fat-bodies, nevertheless they will feed on their first day of life.

Predators

Unlike most other species of sea snake, the Yellow-bellied Sea Snake does not seem to have many predators. In places where the snakes occur in large numbers together with potential predators (large fish, sea birds and marine mammals), no attempts at predation have been observed. The bright colouration of this species serves as a warning, not only that the snake is highly venomous, but also unpleasant and possibly even toxic to ingest. In experiments where skinned Pelamis pieces were offered to predatory marine fish, the fish refused to eat it, and those tricked into eating the meat regurgitated it soon after. In the few known records of natural predation on these snakes, both predators (a pufferfish and a leopard seal) regurgitated the snake afterwards.

Yellow-bellied Sea Snakes are fouled by a number of different marine invertebrates, including a species of barnacle that grows only on sea snakes. Most of these organisms do not directly harm the animal; however if the infestation is heavy the resulting drag can affect the snake’s performance. By frequently knotting and shedding its skin, the snake is effectively able to rid itself of these organisms.

The species’ recorded endoparasites include cestodes (tape worms) and nematodes (round worms).

Danger to humans

Most people are only likely to encounter a Yellow-bellied Sea Snake if a sick or injured animal drifts ashore. Although these specimens are usually in poor condition, they still pose a risk if they are picked up or wash against a person in the surf. If roughly handled this species is likely to bite. The fangs are quite short (~ 1.5mm) and only a small dose of venom is usually injected, however this venom is highly toxic and contains potent neurotoxins and myotoxins. Symptoms of envenomation include muscle pain and stiffness, drooping eyelids, drowsiness and vomiting, and a serious bite can lead to total paralysis and death. Anyone suspected of being bitten by a Yellow-bellied Sea Snake should seek medical attention immediately, even if the bite appears trivial (sea snake bites are initially painless and show no sign of swelling or discolouration). This species has caused fatalities overseas, however none have been recorded in Australia.

In cases of sea snake stranding, contact your local wildlife authority or wildlife rescue service. Do not attempt to pick the snake up and return it to the sea as it is unlikely to survive. Holding some sea snakes in a tilted position out of water for a few minutes can be enough to injure or kill them, as they are unable to maintain an even blood pressure in their bodies without being supported by water.

Evolutionary relationships

True sea snakes are part of the Australian elapid radiation, and appear to have evolved from a Notechis- or Hemiaspis-type live-bearing ancestor.

References

Cogger, H. (2000) “Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia”, Reed New Holland

Greer, A.E. (2005) “Encyclopedia of Australian Reptiles : Hydrophiidae”, Australian Museum

Greer, A.E. (1997) “The Biology and Evolution of Australian Snakes”, Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty Ltd

Ehmann, H. (1992) “Encyclopedia of Australian Animals : Reptiles”, Australian Museum, Angus & Robertson

Heatwole, H. (1997) “Sea Snakes”, revised edition, UNSW Press

Wilson, S. and Swan, G. (2008) “A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia”, Reed New Holland