Scary by name but not by nature

Coined the name ‘Vampire Squid from Hell’, new research reveals there is absolutely no blood-sucking involved.

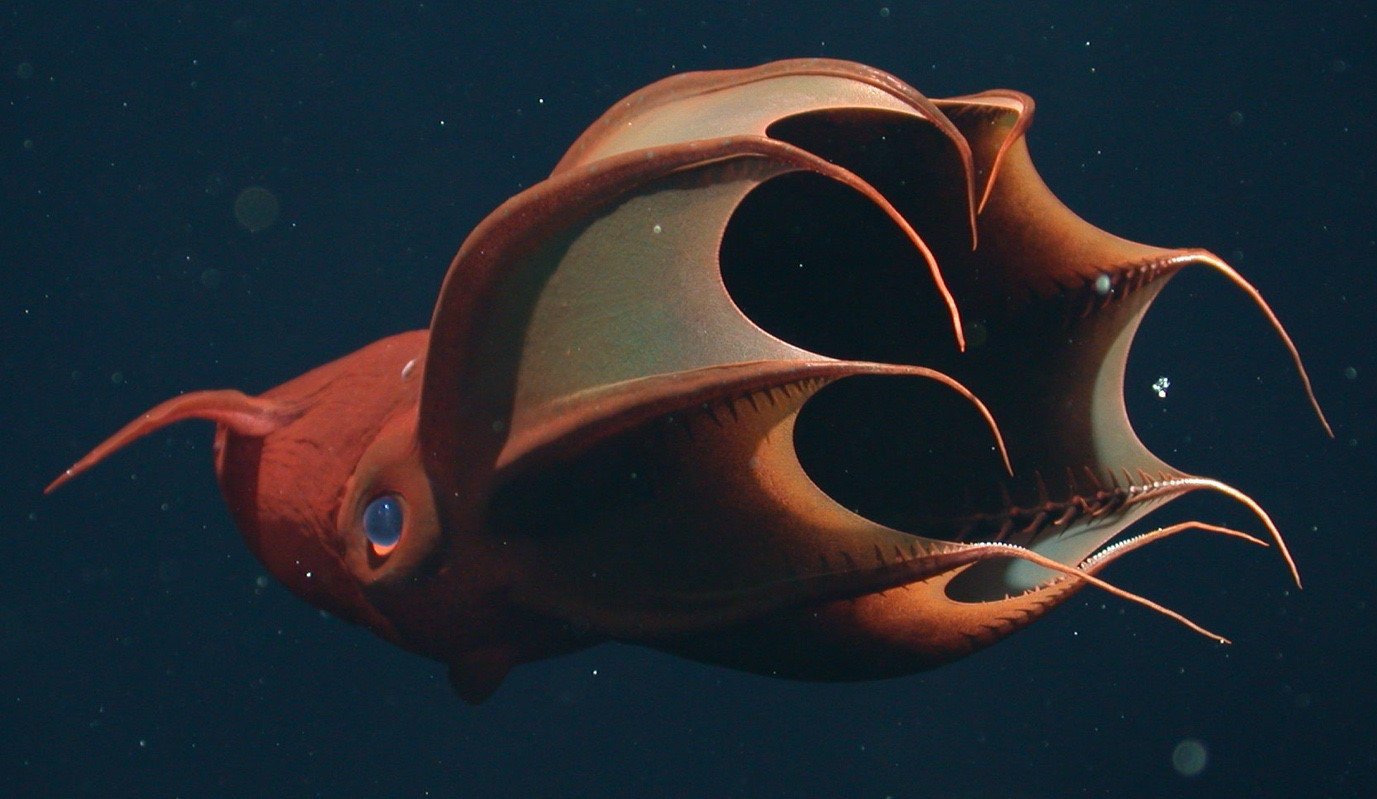

A study examining the chemical composition of the hard ‘beaks’ of these molluscs has provided information regarding their diets. Vampire squids are widely distributed deep-water cephalopods (the group to which squids, cuttlefishes and octopuses belong). Until recently, very little was known about their behaviour and habits. Like many cephalopods found in the deep sea, they are very soft and gelatinous and damage easily when collected in nets. As a result, preserved museum specimens look like dark blobs of jelly. Their dark colour and velvety-looking cloak-like arm webs led to their scientific name, Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun, 1903, literally meaning ‘Vampire Squid from Hell’.

Live Vampire Squid photographed in Monterey Bay

Image: Monterey Bay Aquarium (MBARI)© MBARI

Freshly trawled Vampyroteuthis collected in the Great Australian Bight by a team on the RV ‘Investigator’. Note the black skin in the freshly caught (and very damaged) specimen.

Image: Mandy Reid© Australian Museum

It has only been in recent years, through the use of submersibles equipped with underwater cameras, that the beauty of these animals in life has been captured. Much of this work has been done through the Marine and Biological Research Institute (MBARI) based in Monterey Bay, California. We now know how they swim, by gently flapping their small paddle-like fins and pulsating the web of tissue linking each of their eight arms.

As in all cephalopods, these animals have a parrot-like beak at the base of the arms. Beak samples obtained from the Australian Museum Research Institute’s Malacology collection were used to contribute to a stable isotope analysis, that included 104 vampire squids from museum collections around the world. (Isotope analysis is the identification of an isotopic ‘signature’ based on the abundance of certain stable isotopes and chemical elements within compounds found, in this case, beak tissue.)

Left, upper beak; right, lower beak from a Vampire Squid. The beak sits at the base of the arms and the two parts fit together in a parrot-like arrangement.

Image: Alexey Golikov© Alexey Golikov

Preserved specimen from the Australian Museum Malacology Collection

Image: Mandy Reid© Australian Museum

The analysis was used to measure the proportion of stable nitrogen isotopes stored in the animals’ hard parts, which, in turn, reflects what part of the ecological food chain or ‘trophic level’ the animal occupied. (For example, sheep, in consuming plant matter, occupy a lower trophic level than sharks that, by eating other vertebrates, occupy a high trophic level.) The proportion of stable carbon isotopes provides information on the foraging habitat. Typical cephalopods are active high-level predators and occupy a high trophic level and also tend to show an increase in their trophic level throughout their lives (i.e. they feed on prey higher up in the food chain as they grow).

Our results, presenting the first global comparison for a deep-sea invertebrate, demonstrate that V. infernalis, in contrast with other cephalopods, shows a decrease in nitrogen isotopes and trophic level throughout their lives, coupled with niche broadening. That is, juveniles are very active and mobile zooplanktivores, feeding on a wide range of marine animals found in the plankton, such as shrimp and fishes. These foods are concentrated in particular parts of the water column. As they mature and grow, they gradually switch to become slow-swimming opportunistic consumers (rather than active predators) and ingest particulate organic matter — food that occupies a much lower level in the food web. Particulate food is found over a much broader area and depth range in the deep-sea, thus the adults are able to occupy a much broader ecological range, or ‘niche’ than do the juveniles.

These traits have enabled the success and abundance of this relict species inhabiting the largest ecological realm on the planet. The research also serves as an example of how the study of preserved museum specimens can provide unexpected information relating to animal biology and behaviour.

Dr Mandy Reid, Collection Manager, Malacology, Australian Museum Research Institute

More information:

- Golikov, A.V., Ceia, F.R., Sabirov, R.M., Ablett, J.D., Gleadall, I.G, Gudmundsson, G., Hoving, H.J., Judkins, H., Pálsson J., Reid, A.L., Rosas-Luis, R., Shea, E.K., Schwarz, R. & Xavier, J.C. (2019). The first global deep-sea stable isotope assessment reveals the unique trophic ecology of Vampire Squid Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Cephalopoda). Scientific Reports 9: 19099. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55719-1.

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). https://www.mbari.org/