How can you tell the difference between a Cane Toad and a native Australian frog species?

Identifying whether a backyard guest is a native frog or a Cane Toad can be tricky: here’s some tips to help!

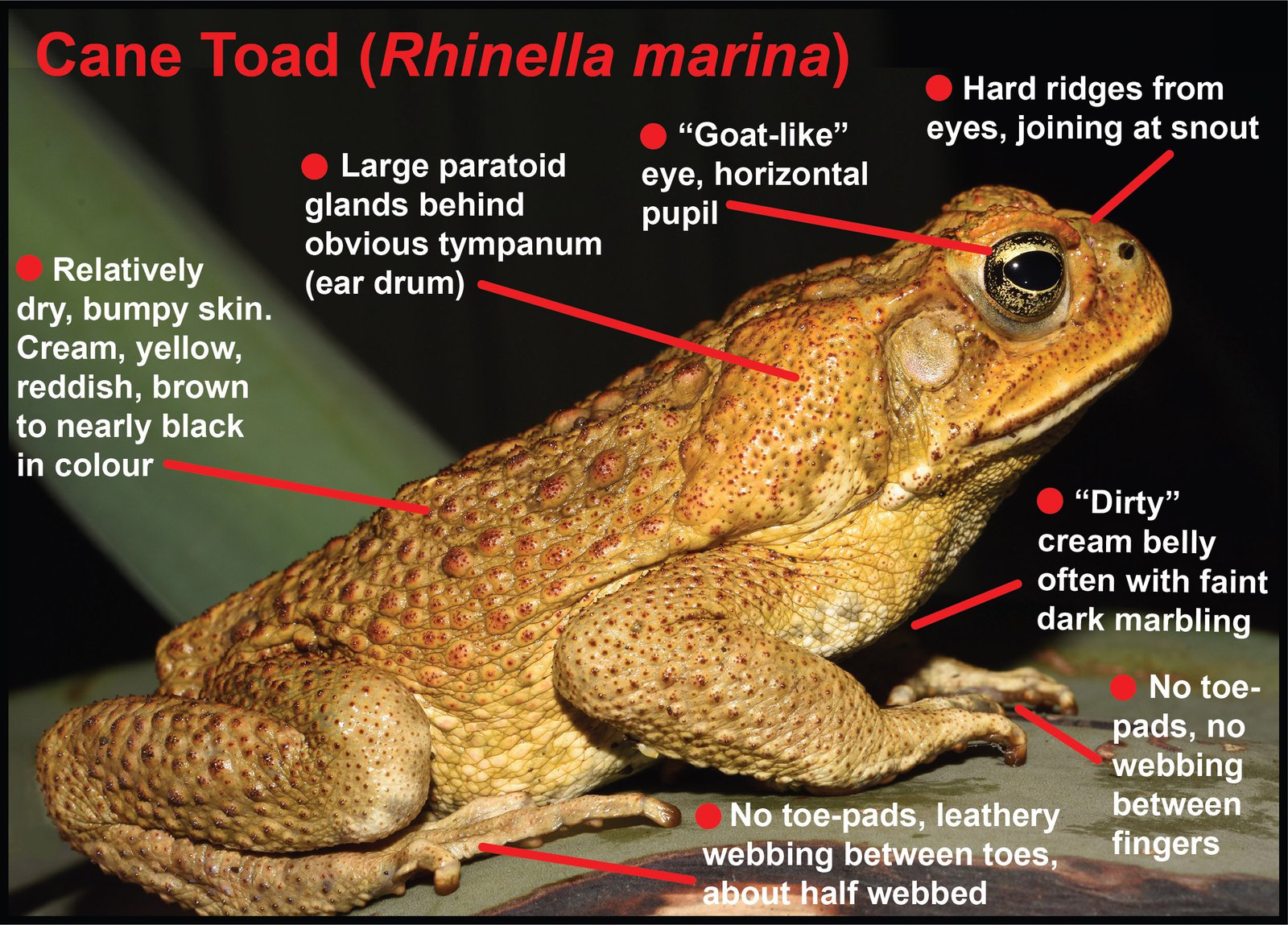

Cane Toad identification

Image: Jodi Rowley© Australian Museum

Cane Toad or native frog? You’d think that would be an easy question to answer, but it’s not always that straightforward. With over 240 native species of frog in Australia, many of which share features with Cane Toads, it can be difficult to identify a Cane Toad. This is especially true if you’re in parts of Australia where Cane Toads are not a familiar sight.

Cane Toads (Rhinella marina) were introduced into Australia in 1935 in north Queensland in an unsuccessful attempt to control cane beetle. Since then, they have spread west across the Northern Territory and into northern Western Australia and south into far northern New South Wales. Cane Toads are considered pests largely because of their impact on native species. Predators including quolls and goannas, which are poisoned by the toads, have been particularly hard-hit.

Cane Toads are occasionally accidentally transported by humans to places far outside of their current range in Australia. They may hitchhike in loads of timber or in pot plants, or anything that they might take shelter in. Recently, Cane Toad stowaways have been picked up in Canberra and Sydney, causing people in these areas to be on the lookout for any more toads. But some of our native species can look superficially toad-like, and our native species can be mistaken for toads, and even killed due to their mistaken identity. It’s therefore vital to know how to distinguish Cane Toads from native frog species, and to report (not kill!) any Cane Toads spotted outside their known range in Australia.

Cane Toads are one of the largest species of toad in the world. They are typically 10-15cm in body length as adults, but juveniles can be tiny, and some adult females can grow to over 20cm. Cane Toads are heavy-set animals with relatively short limbs and skin with a dry and bumpy (or 'warty') appearance. They tend to sit more upright than many native frog species, and crawl or walk more than leap long distances (but many native frogs do that too). They lack toe-pads and they're not able to climb up walls.

© Jodi Rowley

No single feature can be easily used to distinguish Cane Toads from native species, but one of their most distinctive features is their large paratoid glands behind their shoulders. Some native species such as toadlets in the genus Uperoleia also have paratoid glands, though, so it’s important to use more than this feature to identify a Cane Toad. It also helps to know what your local native frogs look like (see the image above of some native frog species commonly mistaken for Cane Toads in NSW).

One of the most distinctive features of the Cane Toads is their call - it’s a low, long, trill, and it’s not like the call of any native species (listen to the call on the free FrogID app or website). Cane Toads are most likely to call at night, particularly in the warmer nights and after rain.

A great way to monitor your local native frogs, and detect any calling Cane Toads, is to download the free FrogID app and record the calls coming from your pond, dam or local creek often (daily if possible!). Recordings of Cane Toads from locations where they aren't already established are incredibly important, but even if Cane Toads have been established in your area for years or decades, we want their calls! Recordings of Cane Toad and native frogs submitted via the FrogID app will help us understand where and when your local Cane Toads, and native frogs, are breeding- vital information for developing conservation strategies.

If you believe you have spotted a Cane Toad in an area where it’s not established already, please take a photograph and report it to your local authority (in NSW, please report via this link or call 1800 680 244).

Dr Jodi Rowley

Curator, Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Biology, AMRI & UNSW