Aussie marsupial diggers united!

Marsupial moles and bandicoots are related according to first genomic-scale data for Australian marsupials.

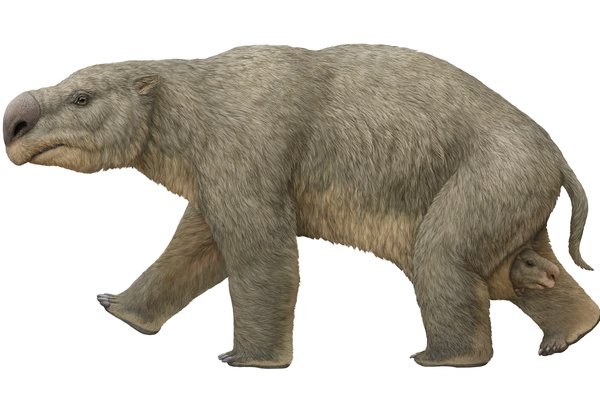

A golden bandicoot (Isoodon auratus), showing its well-developed digging claws.

Image: Emily Miller© Emily Miller

After decades of debate and uncertainty, the relationship of the enigmatic marsupial mole to other Australian marsupials has finally been resolved. This was achieved by analysing DNA sequence data from over 1500 genes obtained from representatives of 18 different marsupial Families. This is the largest genetic data set yet assembled for marsupials.

Living marsupials are found in both Australasia (Australia, New Guinea, Wallacea) and the Americas. However, it is in Australasia that the largest number of species and diversity of forms occur. Since the breakup of Gondwana, Australia’s marsupials have evolved and diversified in splendid isolation resulting in such well known and iconic creatures such as koalas, wombats, bandicoots, kangaroos, numbats and possums. Since marsupials rapidly radiated into a diversity of species in Australia, tracing their evolutionary history has proved difficult, with many studies producing contradictory results.

© Australian Museum

Amongst the least known and most difficult to place marsupials are the bizarre and enigmatic marsupial moles which spend their lives underground in the sandy deserts of Central Australia. Marsupial moles rarely come to the surface and so are extremely difficult to observe or study. Their bodies are so highly modified for their subterranean existence that establishing their relationships with other marsupials has proved difficult. Marsupial moles lack eyes and external ears and their forelimbs are highly modified to function as shovels to facilitate their continuous tunnelling.

The advent of recent genomic-scale methods, which allows data from >1000 genes to be generated and examined, and novel methods of data analysis raises hope that some of the long standing uncertainties in marsupial evolution can be resolved. In our first study we examined relationships amongst 18 of the 22 major marsupial lineages (Families) using data from ~1550 different genes. These data produced a strongly supported pattern of evolutionary relationships (phylogenetic tree) that clarified several long-standing controversies.

Intriguingly, this new analysis showed that marsupial moles were most closely related to the bandicoots and bilbies (another group of Australasian marsupials famous for their digging activities). While some previous morphological studies had proposed this relationship, previous genetic studies had instead suggested relationships to either carnivorous marsupials (dasyurids) or more distantly to a combined group of dasyurids and bandicoots.

In another twist, our study has shown that the closest relative of the kangaroos, wallabies and rat-kangaroos (macropodoids) is most likely to be the ringtail possum group (petauroids) rather than the brushtail possum group (phalangeroids). Previous molecular studies have supported both these options and our radically expanded data set was able to offer some explanation for these apparent disagreements. While most of the genes we examined supported the first relationship, about one third of the genes actually supported the alternative arrangement. This finding highlights the complexity and differential nature of the evolutionary processes that occur at individual genes across the genome when lineages diverge rapidly and underscores the need to examine genomic-scale data to comprehensively answer these fundamental questions. Thanks to this solid foundation we are now in a strong position to further investigate the evolutionary history of Australasia’s marsupials as part of the Oz Mammals Genomics project which is reliant on the invaluable tissue and specimen collections held by the natural history museums of our region.

Dr Mark Eldridge, Principal Research Scientist, Australian Museum Research Institute

Dr Linda Neaves, Australian Museum Research Institute.

Dr Sally Potter, Research Associate, Australian Museum Research Institute. Postdoctoral Fellow, Australian National University

Dr Rebecca Johnson, Director, Australian Museum Research Institute