Sharks: The power of pure visual presence

At the AM we herald all species as icons. Indeed, I regularly say we have 22 million objects and specimens in the collection and with those come more than 22 million stories – a total treasure trove to be discovered under one roof.

Yet there’s little doubt in nature’s pantheon of fantastic visual storytellers, sharks have always been the ultimate icon of the oceans, captivating curious and utterly awed audiences.

Sharks are instant impact. They invoke an immediate projection of our senses. Often silence. Fear. Fierce, sleek, beautiful, myths, facts and stats. They are a dominant and diverse species for the power of the visual image.

Speaking at the opening of Sharks, the largest homegrown blockbuster exhibition the AM has ever created, legendary conservationist Valerie Taylor helped us think about why understanding more about sharks – some 183 species can be found around Australia, roughly half of all shark species that exist – is so critical to us humans too, balancing the food web, keeping prey populations healthy and vital habitats healthy. Healthy oceans mean healthy us. Bringing this message home means seeing them and understanding them up close.

© Australian Museum

As well as introducing her new National Geographic documentary on sharks, the opening served as an opportunity for visitors to see the Australian Geographic Nature Photography of the Year exhibition, which happens to feature 14 phenomenal shark images.

And when you see the sharks our scientific model makers have produced, in full glorious detail, so close and out of their natural habitat, it’s such an instant leveller in being present. In the moment. This is what we need to start conversations around looking after our ocean environment.

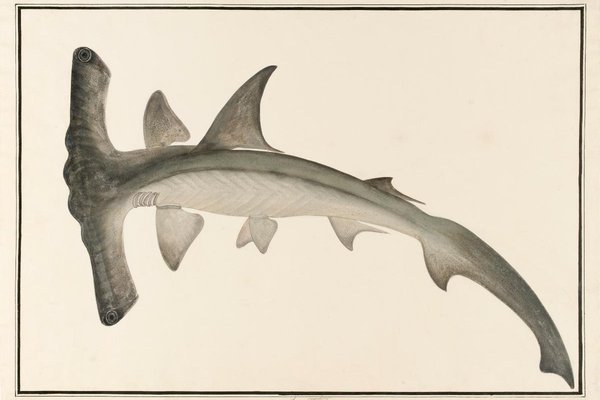

These fierce predators’ visual presence, so clearly bursting with primal sensory perception, amplifies our own primal senses, our emotions, our sense of self. Interactively, we are even showing how to navigate a shark’s world as if you’re within a shark body, looking through a hammerhead’s eyes.

From the stunning underwater films of Jacques Cousteau and Ron and Valerie Taylor to monumental myth creator movies like Jaws, this raw connection with a single species lends itself to storytelling in bucketloads; the discoveries, dramas, myths, misunderstandings and corrections, sharks are a truly magnificent lever for instant conversations, contextualising our vulnerability even as we marvel at their sheer power in the water.

© Australian Museum

So, sharks and the photographers and filmmakers who cover them, provide an effortless communications lever into opening instant and enthused conversations about climate change and ocean protection.

Sharks are apex predators. When we lose or pirate them from the ocean ecosystem - and many shark populations have declined by 90% due to overfishing, climate change and habitat loss - we upset the ocean’s delicate life balance – as projects such as the work the AM does at its Lizard Island Research Station for the past 50 years or National Geographic’s Pristine Seas have been showing for many years.

For all we’ve done to them, we are sharks best allies. They barely make a noise, and yet their visceral power, still or in motion, their very survival prompts us to think about this evolution of the oldest living vertebrates on our planet, teaching us humans about our own origins in turn; even better, their aerodynamic shape inspires universal design for our tools and vehicles.

We were thrilled to welcome approximately 30,000 visitors to Sharks during the two weeks of the recent September school holidays and can’t wait to have more people see this AM blockbuster exhibition that helps start vital conservation conversations.

© Australian Museum