Debunking the myth that Aboriginal stories are just myths: the Yamuti and the megafauna Diprotodon

Jacinta Koolmatrie is an Adnyamathanha and Ngarrindjeri person who works in the South Australian museum sector.

On this page...

Since the beginning of time my ancestors have been telling stories. These stories, derived from the land, waters and skies. We express our stories using our voice and through our actions. They are told at night, when the fire crackles and the stars are bright. They are told through the marking of the walls using sacred pigments the land has provided for us. They are the foundations of our songs and dances. Our language itself would not exist without these stories.

When our lands were invaded, the ways our stories were told changed. Those who were not part of our communities – those who were privileged to hear them – documented every detail that they could understand. These people were fascinated with our stories. They kept close and learnt our languages in order to understand them fully. When it came to sharing our stories, they lessened their importance. They said our stories were “myths” and in doing so, they turned them into myths.

In reality, the term “myth” does have multiple meanings. It could be something imagined, but it could also be something based on reality. At some point the English-speaking world unofficially decided that the word myth would solely be understood as stories that were not real. As expected, many people placed Aboriginal stories into the category of the imaginary. But they always stayed truthful to us.

The reality is that we could never see them as myths because they have always had real world implications. As kids we were always told stories that were there solely to protect us. Some of them seemed incredibly far-fetched, although as kids they had never been more real.

As a young Adnyamathanha kid, I was told the story about the Yamuti. The Yamuti was a very large and scary animal that specifically looked to steal little kids. This story was not told in a way that placed it in the past, the Yamuti existed in real time. We were always told that if we ever saw the Yamuti we had to run to the nearest tree and climb high, because the Yamuti had one flaw, the Yamuti could not look up. Despite us little kids having this one advantage, the thought of being taken by the Yamuti was scary enough to make us never want to leave our mothers side, especially if we were outside in the dark. But even when we were inside a house, the story instilled that much fear in us that it would make us lock all the doors, shut the windows and go to bed. The Yamuti was not something we were interested in seeing ourselves.

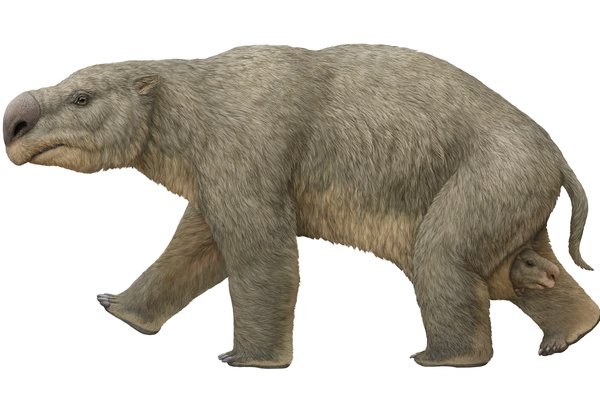

One of the striking descriptions of the Yamuti was that he is very big. Bigger than us kids especially. But this isn’t a unique description, many of the animals in our stories are big. Thousands of years ago megafauna were abundant on this land. One animal in particular was the Diprotodon, the largest marsupial to have existed. The Diprotodon was incredibly large and thought to have been a browser, eating plants like shrubs. However, it’s mostly believed to have been a harmless animal.

Thinking more about the Diprotodon’s physical description, it is oddly similar to that of the Yamuti. Interestingly, I was even told that our understanding that a Yamuti could not look up, did show some potential of being present on a Diprotodon’s skeleton. Of course, our understanding of the behaviour of a Yamuti does not really line up with the Diprotodon’s behaviour. But maybe it gives some insight into a characteristic that Palaeontologists aren’t yet aware of, or even something they may never be aware of.

© Australian Museum

The story of the Yamuti only relates to children, adults weren’t targeted. There’s some potential that a Diprotodon was particularly dangerous for children. Imagine living amongst an animal that size, I’m sure there were times children were trodden on or maybe they were mistaken for baby Diprotodons and literally taken away!

If the Yamuti and the Diprotodon are the same animal, this shows an incredible depth of knowledge that has flowed through thousands of Adnyamathanha generations. In our region the most recent dating of bones is no younger than 40,000 years!

Whether or not you believe the Diprotodon is the Yamuti, our stories are derived from the truth. Something happened over 40,000 years ago that made my ancestors tell a story to protect their children. This relates to all of our stories. They simply weren’t told to pass the time, these stories were created to help us live on this land. The most amazing thing about all of this is that despite animals becoming extinct, lands changing, and our stories being reframed as myths, they have prospered right through to today.

© Jacinta Koolmatrie