Salps

sea squirt

Introduction

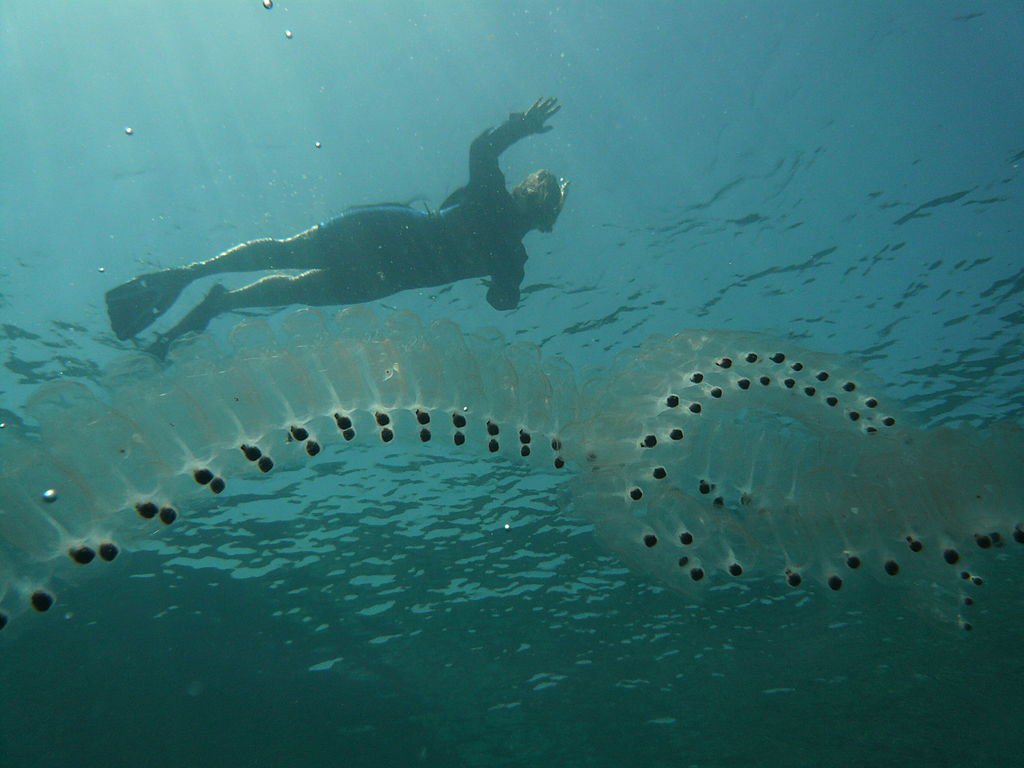

Despite looking rather like a jellyfish, salps are a member of the Tunicata, a group of animals also known as sea squirts. They are taxonomically closer to humans than jellyfish.

Salps are classified in the Phylum chordata; they are related to all the animals with backbones. Larval salps have a notochord running down their back, a tough, flexible rod which protects the central nerve cord and provides and attachment point for muscles. Adults lose their notochord as they grow, but it is one of the ways we can tell that sea squirts are the closest living relatives of the vertebrates.

Identification

Salps are semi-transparent barrel-shaped marine animals that move through the water by contracting bands of muscles which ring the body (the body is referred to as a test). When found washed up on shores they are often mistaken as jelltfish. The contracting muscles draw water in the front of the test and out the rear. Salps feed by filtering plankton and algae and move using an incredibly efficient jet propulsion system, one of the most efficient examples of jet propulsion in the animal kingdom.

Habitat

Offshore marine environments

Distribution

Salps are common in equatorial, temperate, and cold seas. The most abundant concentrations of salps are in the Southern Ocean. Tunicates (salps and a closely related class larvaceans) are the second most abundant class of zooplankton (the first being copepods). Dense salp swarms have often been observed off Sydney (Heron and Benham, 1984) and shown to drastically reduce phytoplankton abundance (Humprey, 1963).

Feeding and diet

Salps are non-selective filter feeders eating everything that they trap in their feeding net. Although the mesh of their feeding net is efficient enough to catch a variety of different sizes of particles from bacteria to larva, their main food is phytoplankton.

Other behaviours and adaptations

Salps have a complex life cycle, growing so fast that they can grow to maturity in 48 hours. They are thought to be the fastest growing multicellular animal on Earth, increasing their body length by up to 10% per hour. This quick turnaround time enables salps to take advantage of algal blooms, increasing their population size rapidly when there is a sudden abundance of food. Because of this, salps are very important for cycling nutrients through the different depth zones of the ocean. As they move up and down through the ocean eating and excreting they spread nutrients downwards to other ocean communities.

Life history cycle

The life cycle is an obligatory alternation of sexual (hermaphroditic, gonozooid) and asexual (oozoid) generations.

Breeding behaviours

Salps have a complex life cycle alternating between a sexual and asexual form. Sexual forms are called aggregates because they form a colony while asexual forms are solitary. All females have one or two eggs when released by a solitary parent. Mating occurs with larger male aggregates and embryos grow inside an aggregate body by being nurtured through a placenta. When embryos mature, they are released and the mother aggregate becomes male. Released embryos grow to be mature solitaries that asexually reproduce 'stolons' - buds of young aggregates.

Each parent produces only one embryo and nourishes it via parental blood through a kind of placenta. On release, the asexually reproducing stage (oozoid) buds off a chain of between 20 and 80 identical embryos. These will eventually separate to become sexually reproducing forms.

© Lars Plougmann

Economic impacts

Sinking fecal pellets and bodies of salps carry carbon to the sea floor, and salps are abundant enough to have an effect on the ocean's biological pump. Consequently, large changes in their abundance or distribution may alter the ocean's carbon cycle, and potentially play a role in climate change.

Predators

Salps are an important food item for many fishes including the Smalleye Squaretail, Chinaman Leatherjacket, Ocean Sunfish, and the Blue-ringed Angelfish.

Danger to humans

None

References

Australian Antarctic Division

Further reading

Edgar, G.J. 1997. Australian Marine Life: the plants and animals of temperate waters. Reed Books. Pp. 544.