Stolen Generations

On this page...

Curators’ acknowledgement

“We pay our respects and dedicate the Unsettled exhibition to the people and other Beings who keep the law of this land; to the Elders and Traditional Owners of all the knowledges, places, and stories in this exhibition; and to the Ancestors and Old People for their resilience and guidance.

We advise that there are some confronting topics addressed in this exhibition, including massacres and genocide. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be advised that there may be images of people who have passed away.”

Laura McBride and Dr Mariko Smith, 2021.

Stolen Generations

Aboriginal children were removed from their families from the early decades of the colony. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it became official policy for state governments. These children are known as the Stolen Generations. The Australian Federal Government formally apologised in 2008, however since then the number of First Nations children in out-of-home care has increased.[1]

Families never recover from the grief of their children being taken away. Ironically, the motivation for removal was to give them a “better” life in white society, but many of the Stolen Generations suffered abuse and dysfunctional childhoods, and this trauma has had intergenerational impacts. Some children are still trying to make their way home to family and culture; some never made it in this life.

Read more here.

Stolen Generations institutions map 1900-1980

Stolen Generations Institutions Map 1900-1980

(detail showing the state of NSW, and cities of Melbourne and Brisbane)

Data sourced from The Healing Foundation.

© Australian Museum

Stolen Generations Institutions Map 1900-1980 (detail showing the state of NSW, and cities of Melbourne and Brisbane).

Data sourced from The Healing Foundation.

The national map is regularly updated at: https://healingfoundation.org.au/map-stolen-generations-institutions/ .

The Healing Foundation’s map includes the locations of numerous institutions across Australia where children of the Stolen Generations were taken upon removal from their families. Note how children were moved into large cities and towns far from their homes, making it almost impossible for families to find them.

Rules and Regulations for the Management of The Aborigines

Rules and Regulations for the Management of The Aborigines; on, Black Native Institutions of New South Wales; Established at Parramatta On the 18th of January, 1815

Ink on paper.

Loan from the State Library of New South Wales.

© State Library of New South Wales

Rules and Regulations for the Management of The Aborigines; on, Black Native Institutions of New South Wales; Established at Parramatta On the 18th of January, 1815

Ink on paper.

Loan from the State Library of New South Wales.

The first colonial institution planned for the assimilation and training of Aboriginal children was the Native Institute in Parramatta, Sydney. The aims were to “improve” and “civilise” the children, to “render their habits more domesticated and industrious”. It also aimed to improve relationships with local clans in the Sydney region. Once children entered institutions they could not return to their families, and it was very rare to be allowed visitation.

The practice of removing children and training them in schools or homes did not end officially in some states until the 1970s. Many of these children and their descendants are still trying to make their way home. We mourn for those who never made it.

One Way Ticket to Hell 2012-2020

One Way Ticket to Hell 2012-2020

Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri

Acrylic on canvas.

Copyright: Aunty Fay Moseley

© Aunty Fay Moseley

One Way Ticket to Hell 2012-2020

Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri

Acrylic on canvas.

Copyright: Aunty Fay Moseley

Memories of the Morgue 2020

Memories of the Morgue 2020

Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri

Acrylic on canvas.

Australian Museum Collection Acquisition.

© Artist, Aunty Fay Clayton Moseley

Memories of the Morgue 2020

Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri

Acrylic on canvas.

Australian Museum Collection Acquisition.

Aborigines Welfare Board Exemption Certificate 1955

Aborigines Welfare Board Exemption Certificate 1955

Courtesy of Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri

Reproduction of the certificate.

© Courtesy of Aunty Fay Moseley

Aborigines Welfare Board Exemption Certificate 1955

Courtesy of Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri

Reproduction of the certificate.

Dad had a Certificate of Exemption from the Superintendent of the Aborigines Welfare Board, but this didn’t prevent the police from taking us children away when my parents worked during the day at the local cannery. My father went to war to protect all Australians, but he couldn’t protect his own kids - they just took his children away. Aunty Fay Moseley, Wiradjuri, 2020

Homes are sought for these children, 1934

Homes Are Sought for These Children, 1934

Reproduction of a 1934 newspaper clipping.

© National Archives of Australia

Homes Are Sought for These Children, 1934

Reproduction of a 1934 newspaper clipping.

Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia.

I like the little girl in centre of group, but if taken by anyone else, any of the others would do, as long as they are strong.

Aboriginal children removed from their families were taken to places such as this “half-caste home”, where this group of little girls were photographed and reported as needing help in the form of charity to “rescue them from being outcasts” in Australian society. The justification for such cruelty was that it was an act of kindness to save Aboriginal people from themselves.

Many girls and boys were adopted into families or placed into foster care, generally without their parents’ permission or even knowledge. Lighter-skinned children were preferred since it was considered easier to hide their Aboriginality.

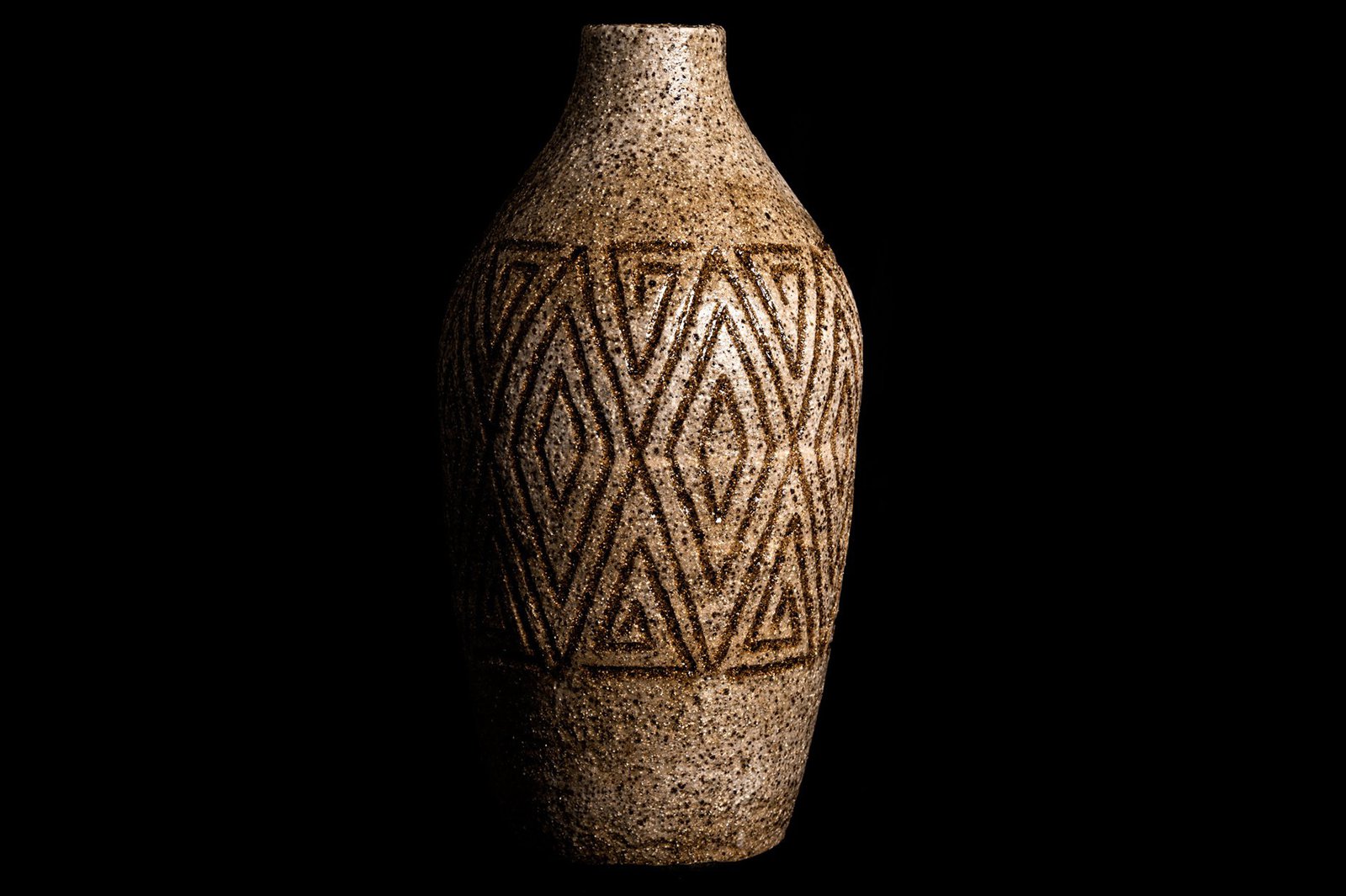

Scarred (Ancestral vase) 2020

Uncle Kevin Sooty Welsh, Wailwan

Stoneware No. 7.

Australian Museum Collection Acquisition.

© Australian Museum

Uncle Kevin Sooty Welsh, Wailwan

Stoneware No. 7.

Australian Museum Collection Acquisition.

Chained Culture 2020

Karla Dickens, Wiradjuri

Mixed media.

Australian Museum Collection Commission.

© Australian Museum

Karla Dickens, Wiradjuri

Mixed media.

Australian Museum Collection Commission.

Hooking the Natives 2020

Karla Dickens, Wiradjuri

Mixed media.

Australian Museum Collection Commission.

© Australian Museum

Karla Dickens, Wiradjuri

Mixed media.

Australian Museum Collection Commission.

Hooked, Caged and Sinking 2020

Karla Dickens, Wiradjuri

Mixed media.

Australian Museum Collection Commission.

© Australian Museum

Karla Dickens, Wiradjuri

Mixed media.

Australian Museum Collection Commission.

Christian missionaries and organisations played significant roles in the Stolen Generations through their running of institutions and homes.[2] Assimilation of children involved the severing of contact to families and communities, and the active destruction of cultural knowledges and identities to be replaced with a new Christian identity and way of life.

These objects bring attention to how Christianity and the Bible were used as tools for restraining culture and how religion was co-opted into the colonial project by colonisers to justify their actions as a means to a greater good.

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Provided by Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Reproductions of photographs.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

© Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Provided by Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Reproductions of photographs.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Provided by Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Reproductions of photographs.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

© Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Provided by Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Reproductions of photographs.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Provided by Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Reproductions of photographs.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

© Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home, undated

Provided by Children of the Bomaderry Aboriginal Children’s Home Incorporated

Reproductions of photographs.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

The Bomaderry Children’s Home, part of the United Aborigines Mission (UAM) in Shoalhaven, New South Wales, was an institution specifically for Aboriginal babies and young children. It has been called the birthplace of Stolen Generations in NSW. The children could be kept until 16 years of age, but often once they turned 10 they were separated and sent to Kinchela Boys Home, Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Girls, or into service.

Places like Bomaderry stand as a testament to assimilation practices which aimed to destroy Aboriginal communities. Without knowing their family or homelands, many ended up staying in the local areas of their institutions.

Sorry 2006

Sorry 2006

Nyree Reynolds, Wiradjuri

Reproduction of the artwork.

Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition.

© Nyree (Ngari) Reynolds

Sorry 2006

Nyree Reynolds, Wiradjuri

Reproduction of the artwork. Australian Museum Collection Digital Acquisition

Kinchela Boys 2020

Kinchela Boys 2020

13-minute animated film shown in the physical Unsettled exhibition. Produced and narrated by survivors of Kinchela Boys Home.

Animated Short Film.

© Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation

Kinchela Boys 2020

13-minute animated film shown in the physical Unsettled exhibition. Produced and narrated by survivors of Kinchela Boys Home.

Animated Short Film.

This film is part of the Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation’s Education Program resources.

The Board may assume full control and custody of the child of any aborigine, if after due inquiry it is satisfied that such a course is in the interest of the moral and physical welfare of such child. The Board may thereupon remove such child to such control and care as it thinks best …

Created by the men who survived Kinchela Boys Home, this animation is to help share and teach about the experience of these men when they were children. This animation includes distressing content but is the truth of what happened at the Kinchela Boys Home. For more information about the Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation and the important work being done by survivors, please see here.

Kinchela Boys Gates 2.0

Kinchela Boys Gates 2.0

Uncle Widdy Welsh, Wailwan.

Metal, wire, paint. Loan from Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation.

© Australian Museum

A key memory for many of the men who were taken to Kinchela Boys Home in Kempsey, New South Wales as young boys was going through the front gates. This was a moment in time and space which marked the point when they were stripped of their names and identities to become a number. When they eventually left Kinchela, they took with them the horrific memories of their experiences.

For the 90th anniversary of the Kinchela Boys Home in 2014, the men wanted to reunite the old gates so they could walk through them again to heal and be free for the first time.

Kinchela Boys Gates 2.0

Uncle Widdy Welsh, Wailwan.

Metal, wire, paint. Loan from Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation.

When we couldn’t get the old gates together, I made these new gates so we could walk through them again as adults and finally be free. I made these gates for our healing. This is now my purpose. Uncle Widdy Welsh, Wailwan, 2020

References:

- Productivity Commission (2020). 16 Child protection services. Australian Bureau of Statistics (Oct 2010). 4704.0 – The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. ABS website; SNAICC- National voice for our children. (2019). The Family Matters Report, 2019. Postscript Printing and Publishing, Eltham.

- Maddison, S. (2014). Missionary Genocide: Moral illegitimacy and the churches in Australia. In Havea, J. (eds) Indigenous Australia and the Unfinished Business of Theology. Postcolonialism and Religions. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.