Predicting and managing koala population growth in South Australia

Australians tend to think of koalas as a species in crisis, iconic animals pushed toward extinction by climate change, disease and habitat loss. While that is true across much of eastern Australia, in South Australia’s Mount Lofty Ranges, koalas are facing the opposite problem: their numbers have grown so rapidly that they are now damaging the very forests they rely on.

© Flinders University, South Australia

Unlike with non-native species such as goats and wild pigs, culling koalas is politically and ethically off the table, and mass translocations are costly, stressful to animals, and rarely successful. So what options remain?

Our new research provides a predictive approach and quantifies the ongoing changes in koala abundance across the Mount Lofty Ranges. We tested a range of non-lethal management strategies (including different fertility-control approaches) to find out which could stabilise the population without compromising animal welfare or straining conservation budgets.

© Frédérik Saltré and Katharina J. Peters

22,000 koalas and counting, but already above healthy levels

The Mount Lofty Ranges hold a lot of koalas. But estimating their actual number is harder than it sounds.

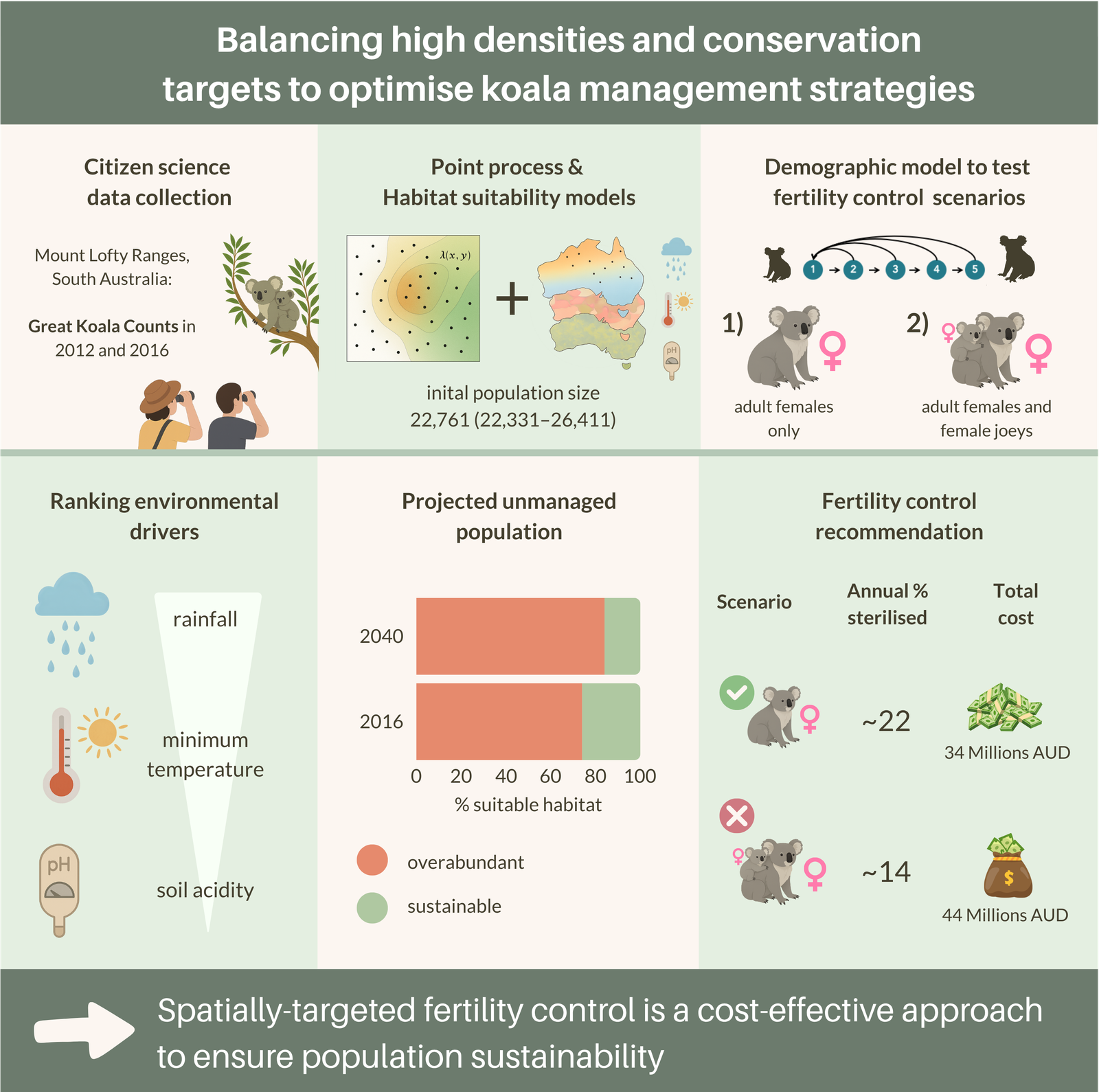

Our modelling approach combined thousands of reports from the Great Koala Count citizen science programs (2012 and 2016) with advanced spatial statistics, to correct for known observation biases, and an estimated layer of habitat suitability.

We estimate 22,000–26,000 koalas across the region which is roughly 10% of Australia’s total population. We found their distribution is shaped largely by rainfall, temperature and soil acidity. Areas with warm minimum temperatures, moist conditions and acidic soils currently support the highest densities.

Expected population size under a no-intervention scenario over the next 25 years. The solid blue line shows the median population trajectory and the shaded envelope represents the 95% confidence interval. The horizontal red dotted line represents the estimated regional population corresponding to the conservation management density target of 0.7 individuals per hectare.

The South Australian government considers ~0.7 koalas per hectare to be the maximum sustainable density for koalas. Our results show that many areas in the Mt Lofty Ranges have already exceeded this threshold, indicating that intervention is needed sooner rather than later.

Avoiding further expansion in new areas

By projecting these results into the future using a demographic model, we showed that, without intervention, the koala population could grow by a further 17–25% over the next 25 years, pushing even more of the landscape into high-density conditions where vegetation damage becomes likely.

Beyond forecasting population trajectories, we also evaluated multiple fertility-control scenarios. These non-surgical, reversible methods are already being applied in small-scale management programs. We wanted to identify the most effective strategy, in terms of associated costs, for stabilising the population and avoiding severe ecological impacts.

We modelled two strategies: (1) sterilising adult females only, and (2) sterilising adult females together with their dependent female young (a method that reduces future breeding more quickly but raises ethical concerns). Both approaches reduced population growth, but one clearly performed better.

Targeting only adult female is the most cost-effective strategy

To keep koala densities below the threshold of 0.7 koalas per hectare, we found that sterilising around 22% of adult females each year is sufficient. The alternative strategy, sterilising approximately 14% of adult females together with their female back young, can also achieve the same outcome, but at a substantially higher cost.

Over a 25-year period, the adult-female-only approach is estimated to cost about AU$34 million, whereas including back young exceeds AU$43 million. For comparison, eradicating feral cats on Kangaroo Island was estimated at more than AU$46 million.

Projected total population size over the next 25 years (left panel) and associated management cost (right panel) as a function of the proportion of mature females sterilised. The solid blue line shows the median population trajectory along with the 95% confidence interval (shaded envelope). The horizontal red dotted line represents the estimated regional population corresponding to the conservation management density target of 0.7 individuals per hectare.

Our results show that broad-scale sterilisation across the entire region is unnecessary; targeting adult females in high-density hotspots alone provides effective population control at a much lower cost.

Why managing "too many" native animals is never simple

The Mount Lofty Ranges koala population is a striking example of a broader conservation dilemma: how do we manage native species that are threatened in some regions yet overabundant in others?

Here, strong public affection for koalas makes lethal control socially unacceptable, but doing nothing risks severe habitat degradation, animal suffering, and long-term ecosystem damage.

We provide a way forward: a humane, targeted and cost-effective strategy grounded in realistic population projections and corrected citizen-science data. More importantly, this is a proactive approach that informs managers to test the likelihood that a conservation plan will succeed or fail before investing substantial resources, helping avoid costly or ineffective actions.

As climate change reshapes habitats and species distributions, such evidence-based and anticipatory approaches will become increasingly essential, especially for high-profile species where public values and ecological needs collide.

Authors: Frédérik Saltré, Katharina J. Peters, Vera Weisbecker, Daniel Rogers & Corey J.A Bradshaw.