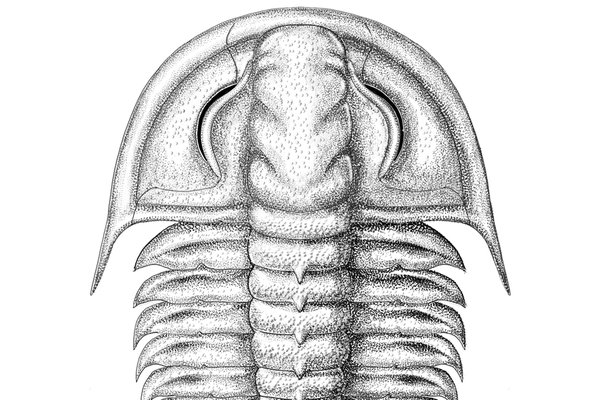

The Great Australian Trilobite

A newly discovered trilobite species, found in the collections of the Australian Museum and Geoscience Australia, is the largest species ever unearthed in Australia. At almost double the size of the previous record holder, it is potentially the third largest trilobite species in the world.

Australia’s depths once teemed with the world’s first underwater giants, unlike anything in today’s oceans. This was 460 million-years-ago, during the Ordovician – a period in Earth’s history when Australia’s red centre was covered in a shallow waterway known as the “Larapinta Sea”. A recent effort to digitise the Australian Museum’s palaeontology collection led to a rediscovery of the nation’s most extensive collection of Ordovician marine fossils. This included dozens of species completely new to science, one of which is the largest trilobite ever found in Australia.

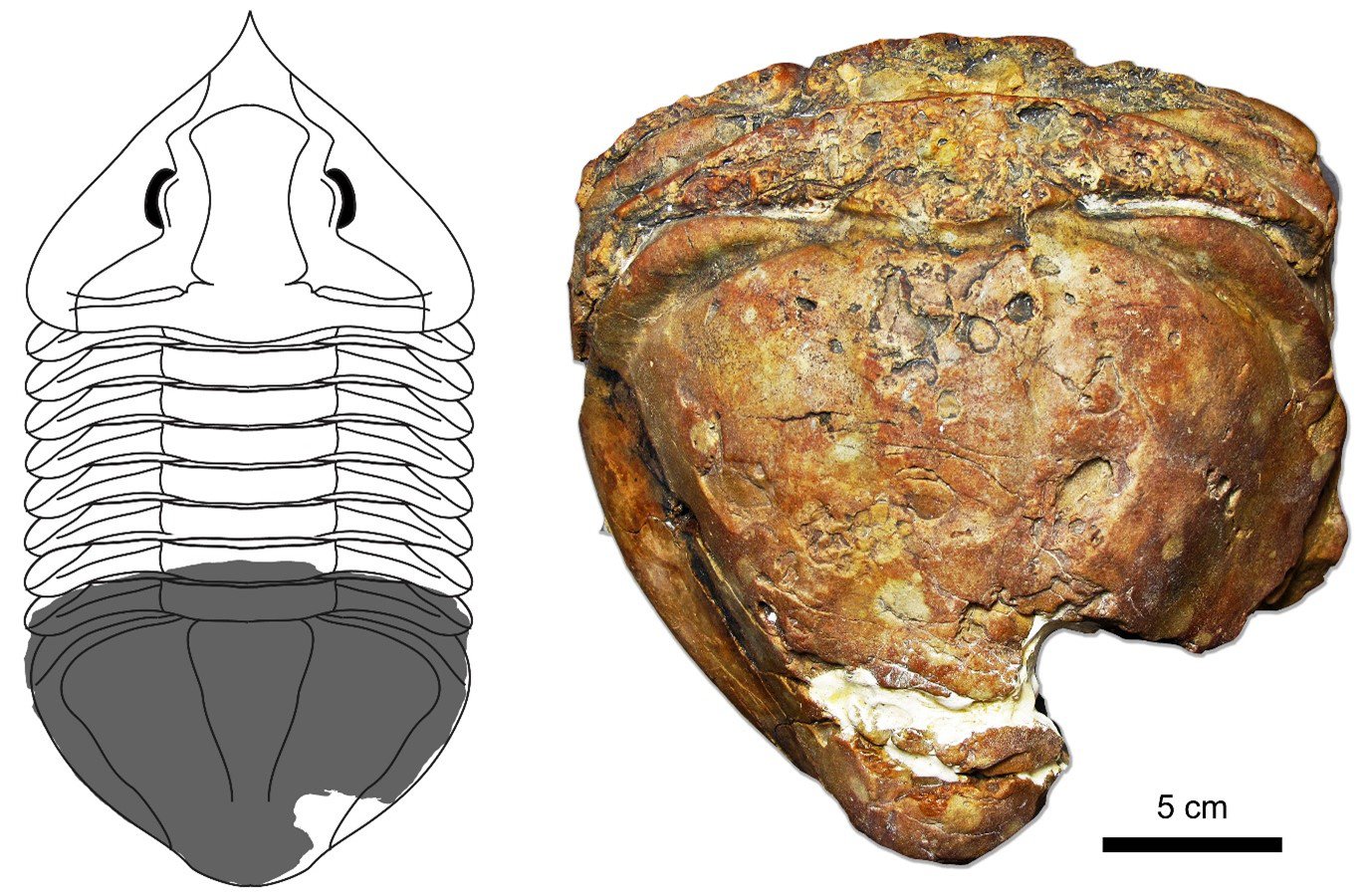

Lycophron titan sp. nov., the holotype specimen on display at Geoscience Australia (right) and a life reconstruction of the animal showing the portion preserved (left).

Image: Dr Patrick Smith© Australian Museum

I remember the first time I visited the fossil display at Geoscience Australia, back in 2013. It was during the first year of my PhD at Macquarie University. The fossil display was then (and still is) laid out in lavished glass display cases with detailed information on every specimen. One specimen, however, stood out. It was only vaguely identified with a label saying “Lycophron sp.” and appeared to be a massive tail from a trilobite found in central Australia. Most trilobites are only 5 to 10 cm in total length, as generally they were rather diminutive, similar in size to modern woodlice (also called slaters, pill bugs or sowbugs). Yet, moderately sized (15 to 20 cm) trilobites from central Australia are not unusual, particular in rocks from the Ordovician Period (approximately 480–440 million years ago). This is because during the Ordovician there appears to have been a pronounced jump in the average and maximum body size of most groups of marine animals. However, this trilobite on display at Geoscience Australia appears to have been a true behemoth – the tail alone was 16.5 cm in length!

Being curious as to the total size of the animal, I did a few back of the envelope calculations. One could assume, since trilobites are made of three major body segments* (a head [cephalon], a body [thorax], and a tail [pygidium]), that you could just multiply one of these dimensions by three. Unfortunately, the calculation isn’t that simple. Trilobites vary widely in terms of overall morphology, with some having tiny heads and long bodies, or huge tails and tiny heads. To make an accurate calculation, I used the ratios of length for the head, body and tail from the next largest species from the same genus, Lycophron howchini. This other species is known from relatively complete individuals found in the same area from slightly older rocks. It’s ratio of head:body:tail was approximately 1.35:2.00:1.92. Hence, multiplying the length of the pygidium (16.5 cm) by 2.74 (i.e. the total length divided by the pygidial length), gives an overall body length of approximately 45.3 cm for a complete specimen (about the size of an average house cat). Whilst this might not sound huge, it is actually rather impressive for a trilobite. In fact, this made it the largest trilobite currently known from Australia. It surpasses the previous record holder, the 21.9 cm Redlichia rex, known from the much older Cambrian rocks near Emu Bay on Kangaroo Island by a significant margin. It also makes it the third largest trilobite in the world, after Isotelus rex (the largest) known from slightly younger Ordovician aged rocks in Manitoba, Canada, and Uralichas hispanicus (the second largest) from younger Ordivician rocks in the Iberian Peninsula. Terataspis grandis from much younger Devonian rocks in North America may also reach larger sizes, however, its length may be exaggerated by very long tail spines and frequent geological distortion overserved in specimens. Regrettably, since the large tail was only a single specimen, I wasn’t able, at the time of my PhD, to confidently identify it as belonging to a sperate (or previously described) species of Lycophron.

Size comparison for a few of world’s largest trilobites. Lycophron titan sp. nov. (second right) is potentially the world’s third largest trilobite. An average trilobite and typical shovel have been added for scale.

Image: Dr Patrick Smith© Australian Museum

Fast forwarding a few years to 2019. At the time I was digitising the palaeontology collections at the Australian Museum. Amongst the substantial collections of megafauna bones from Welling Caves, opalised dinosaurs of Lightning Ridge and the 370-million-year-old fish from central New South Wales, was a sizable collection of Ordovician fossils from central Australia. In particular, fossils from a region scientists call the Amadeus Basin (named after Lake Amadeus). These were unearthed in the 1970’s by the previous curator and collection manager Dr Alex Ritchie and Mr Robert Jones. Alex had been interested in collecting fossil fish, particularly some of the earliest fish in the world. Alongside these fossil fish, he also collected all the other groups of fossil organism – including lots of trilobites! In amongst this trilobite material were fragments of what appeared to be the same species I had seen at Geoscience Australia. More importantly, the material from the Australian Museum appeared to have a head, which was missing in the specimen from the other collection.

With help from funding from the Australian Museum Foundation, myself and my co-author John Laurie at Geoscience Australia were able to visit both collections and photograph these specimens. Comparing this material with other previously described species of Lycophron, we discovered it differed in having a broad, moderately well-defined border on the tail in large adult specimens. This subtle but significant difference was enough to name this animal as a new species. Given its large size, we called it Lycophron titan – after the ancient pre-Olympian Greek gods, the “titans”, which were known for their gigantic size. Alongside this species we also discovered two new trilobite genera (Ghanaspis and Iridis) and four other new species (Eisarkaspis jonesi, Ghanaspis ritchiei, Iridis schoonorum and Norasaphus (Norasaphus) patersoni.

The discovery of these species (in particular Lycophron titan) would not have been possible without the amazing fossils in the Australian Museum collections and Geoscience Australia. This just goes to show the value of having such collection and the benefits of collaborative research between institutions with large fossil collections. Australia, in particular, is lucky in that we have many scientific institutions which house large fossil collections in most of our states and geological surveys. These places are really the factory floors for new (and amazing) species discoveries, and the engine rooms of scientific research.

Dr Patrick Mark Smith, Technical Officer, Palaeontology, Australian Museum Research Institute.

More information:

Patrick M. Smith & John R. Laurie (2021) Trilobites from the mid-Darriwilian (Middle Ordovician) of the Amadeus Basin, central Australia. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, DOI: 10.1080/03115518.2021.1914727