Shark myths and facts

On this page...

1. Sharks are man-eating, blood-thirsty creatures. False.

Sharks do not naturally hunt humans, in fact, according to the American Museum of Natural History, over 75% of all shark species will almost never encounter a human being and/or are incapable of consuming a human. Most occurrences of a shark attack are due to poor water visibility or curiosity rather than predatory intentions, hence why shark bites are much more common than fatalities. While it is extremely rare attacks can occur.

In 2023, the World Animal Foundation reported that there were 69 unprovoked attacks by sharks. Previous reports according to the International Shark Attack File include that in 2019 there were only 64 unprovoked attacks worldwide and 41 provoked attacks.

● ‘Unprovoked attacks’ are determined as incidents in which an attack on a live human occurs in the shark’s natural habitat with no human incitement.

● ‘Provoked attacks’ are defined as when a human initiates interaction with a shark in some way. For example, people feeding sharks, spear-fishers, and divers trying to touch the sharks.

Additionally, the idea that sharks jump out of the water to knock people off their boats is also a myth perpetuated by movies like ‘Jaws’, which largely propelled the killer-shark concept. Whilst some sharks are capable of leaping into the air, the purpose of this is to capture prey.

2. You are more likely to be struck by lightning, or killed in a car accident than attacked by a shark. True.

In Australia, lightning is one of the most commonly encountered and dangerous weather hazards. Five to ten deaths and over one hundred serious injuries are estimated to be caused by lightning every year. Comparatively, there were only 11 unprovoked shark attacks recorded in Australia throughout 2019.

In fact, there are many other animals or common everyday activities that are much more likely to attack and/or kill you than a shark, including:

● The Australian Bureau of Statistics recorded that the most common animal related deaths that occured between 2008 - 2017 were horses, cows, and other “animal transport” with 77 recorded instances.

● Sharks and other marine animals came third on this list - with only a combined total of 26 related-deaths. However, the International Shark Attack File further revealed that there were only 11 recorded unprovoked shark attacks in Australia in 2019.

● Dogs were only fifth on the list, two behind sharks - with 22 recorded related-deaths.

● According to the Global Shark Attack File, mosquitos - through carrying and transmitting diseases - kill more people in one day than sharks have killed over the last 100 years worldwide.

● The Australian Government released their Road Safety Statistics which recorded 1,188 road deaths through 2019.

© Ákos Lumnitzer

3. Sharks are the ultimate and unsurpassed predator. False.

The shark is an apex predator within their marine ecosystem – this means they sit at the top of the food chain and have no, or very few, natural predators. However, this doesn’t mean they are invincible. The greatest threat to sharks is humans! Due to illegal and unregulated fishing and being killed for their fins, shark populations are in rapid decline. The Australian Museum has found that wildlife trafficking, including ivory, rhino horns, live parrots, pangolin scales, and shark fins, is one of the world’s largest illicit transnational trades.

Shark fin soup is a key cause for this illegal trading as it has been considered a delicacy in Asian countries since the imperial Song Dynasty, 960 – 1279 C.E. It is believed to have been introduced to display the emperor’s power and wealth and now symbolises hospitality, prestige, and good fortune.. This demand for the soup has led to the death of more than 73 million sharks every year. The process involves slicing off a shark’s fin while at sea and discarding the remainder of the body back into the ocean. Whilst the shark is often still alive, without the fin they are unable to swim effectively and either die of suffocation at the bottom of the sea or are slowly eaten away by other predators.

Dr John Paxton, a senior fellow in Ichthyology at the Australian Museum, states that, “A combination of relatively late maturity and low reproductive rates means that sharks are unable to replace depleted numbers”.

© Michelle Yerman

4. Shark nets eliminate any chance of being bitten by a shark. False.

Shark mesh nets were introduced to beaches in New South Wales in 1937 with the intention of acting as deterrents for sharks swimming near populated beaches. However, Deakin University environmental science professor Laurie Laurenson claimed that an analysis of 50 years of data on shark mitigation programs show that the nets do very little. As the nets are set on the bottom of the sea floor and do not touch the surface, most sharks swim above or around the nets whilst the ones that are caught are often returning from the beaches.

Also, rather than averting the sharks, the nets are detrimental to endangered shark species and other vulnerable marine life as well. Known as by-catch, marine life caught in shark nets have a very low survival rate and are caught more commonly than sharks. The annual results from the Department of Primary Industries ‘Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2018/19 Annual Performance Report’ found that of the 395 marine animals caught, only 23 were the targeted tiger, great white, and bull sharks.

Dr John Paxton, Australian Museum, states that, “In its attempt to guarantee the impossible [human freedom from shark attack] the Government is paying a very high environmental price, and without public debate. How much time must pass, and how many more sharks and other harmless animals must be killed, before the meshing is gradually but steadily removed?”

5. Sharks do not have bones. True.

Sharks have no bones in their bodies! They are a cartilaginous fish, specifically a member of the Class Elasmobranchii. This includes sharks, rays, and skates, all of which have a skeleton made of cartilage rather than bone. Our ears and nose tip are also made out of this same substance.

Also, the skin of a shark is made up of tiny teeth-like structures called placoid scales, also known as dermal denticles. These are shaped like curved, grooved teeth and make the skin a very durable armour with a sandpaper-like texture.

© Australian Museum

6. Sharks must keep moving in order to survive. False.

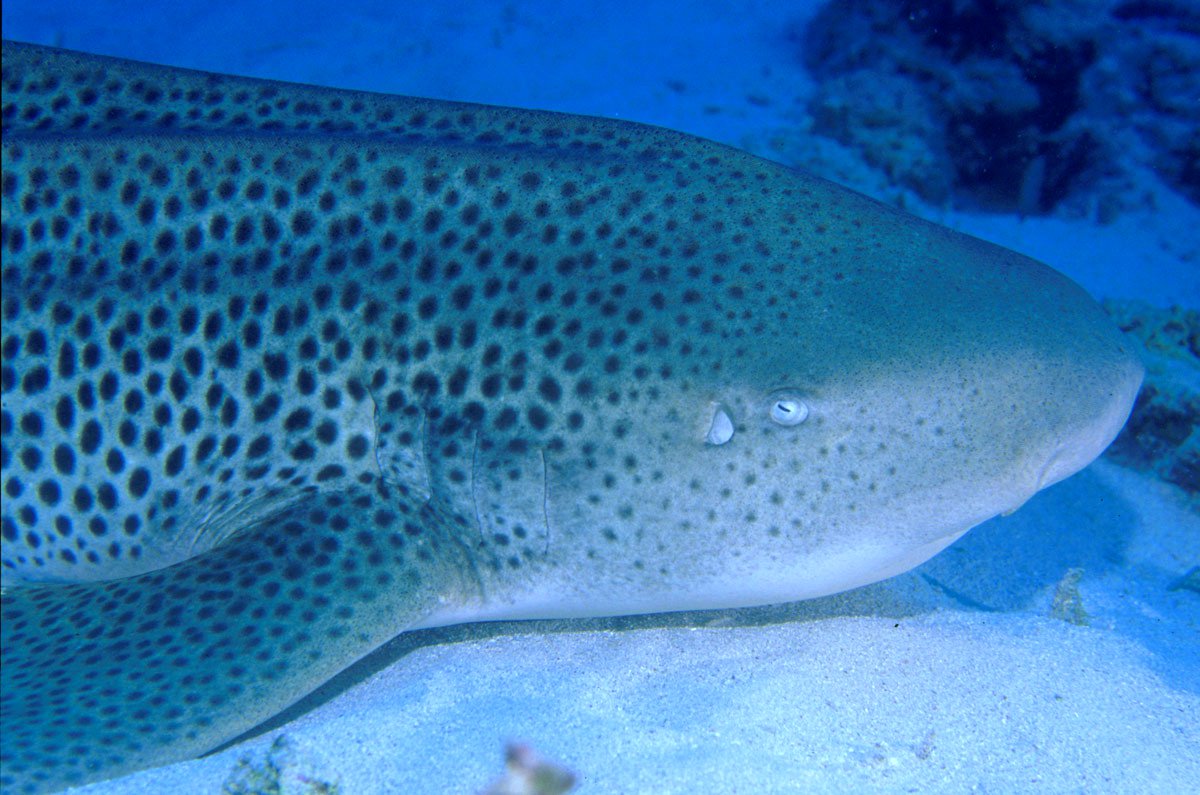

Some sharks need to be continuously moving in order to keep oxygen-rich water flowing over their gills whilst others are able to pass water through their respiratory system by simply using a pumping motion of their pharynx, an example of this includes the Zebra shark (Stegostoma fasciatum).

Nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum), for instance, are able to hang almost stationary in the water. They often rest in groups on the seafloor and breathe through buccal pumping, oral muscles which suck water into the mouth to supply oxygen to the gills.

7. The megalodon was real. True.

The megalodon (Carcharocles megalodon) was one of the largest apex predators to ever exist. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, the earliest fossil found of a megalodon dates to approximately 23 million years ago.

It is estimated that a female megalodon could grow to around 18 metres long and weigh over 45,000 kilograms. To help put that into perspective, great white sharks get to a maximum of around 6 metres long. Scientists have deduced these figures by studying the size of megalodon teeth as unfortunately the cartilage-body of sharks does not fossilise well and so only pieces of vertebrae and teeth can be used in any reconstruction attempts. Megalodon teeth have been found on every continent except Antarctica.

The release of the 2018 film, ‘The Meg’, sparked an influx of new theories and questions as to whether the megalodon could still be alive and swimming somewhere in the deep oceans. Most, if not all, scientists firmly say no to this theory. A species that size who requires warm water would certainly be noticed swimming around. The megalodon shark dominated the ocean for millions of years, until likely becoming extinct around 2.6 million years ago, as the fossil records of the mammoth shark disappear.

© Erik Schlögl

8. Female sharks can reproduce by themselves. True.

Bonnethead, blacktip, and zebra sharks are just some examples of shark species that have the power of parthenogenesis – the ability to have young without a male shark through fertilising their own eggs. This ability is most commonly found in plant and insect species like wasps and ants. Uncovering the ability of some shark’s asexual reproduction means that mammals are the only jawed vertebrate lineage incapable of parthenogenesis, according to Oxford Academic BioScience. The first discovery of this was in 2001 at Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo. An aquarium housing three female bonnethead sharks suddenly overnight held an unexpected new addition - an eighteen centimeter bonnethead pup.

© Australian Museum

9. Sharks can cure cancer. False.

The misconception that sharks can cure cancer dates back to the 1970s when research at the John Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, discovered that cartilage could stop new blood vessels from growing into tissues — a characteristic of malignant tumours. This research began with experiments on rabbit cartilage but soon followed with shark cartilage. In addition, a Florida scientist experimented with sharks by exposing them to known carcinogens and noted the fish did not develop tumours.

However, it has been known for over 150 years that sharks in fact can get cancer. In 2013 Australian researchers discovered a great white shark with a tumour on its lower jaw, the first documented tumour in this particular species. The significance of this misconception is due to its primary role in promoting the hunting and killing of sharks to harvest their cartilage for the production of cancer fighting remedies. This craze has dramatically decimated shark populations. According to Scientific American, North American shark populations have decreased by up to 80% in the last decade.

10. Sharks can change their body temperature to help suit their environment. True.

Many sharks prefer to swim in warm water due to being cold-blooded which means the temperature of their blood is the same as the surrounding water temperature. However, the Laminids are a small group of sharks that have evolved to be able to maintain their body temperature a few degrees higher than their surrounding environment. Some examples of Laminids include the great white, mako, salmon, and porbeagle sharks. This ability to maintain a higher body temperature makes Laminids endothermic – the word “endothermy” means “heat within”.

The greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) which lives in the Arctic waters is distinct to the other endothermic sharks that dwell in such cold waters as it is, in fact, cold-blooded. Instead of producing internal heat, Greenland sharks rely on having a high level of urea and TMAO in order to stabilise proteins against freezing. This chemical makeup also enables hunting at extreme depths of around 2,000 metres without being impacted by the ambient pressure. Rarely seen by humans, this shark is estimated to have a lifespan of 400 years and is likely the oldest living shark on the planet.

© Australian Museum Research Institute

11. Sharks can detect a single drop of blood in the ocean. False.

The notion that a shark can smell a single drop of blood in the ocean has been largely overexaggerated due to the hysteria that often arises when discussing these creatures. Sharks do, however, have an extremely acute sense of smell and a sensitive olfactory system. The ability of sharks to detect miniscule amounts of certain chemicals varies amongst the different species of sharks, however, some can detect their prey at one part per 10 billion which equates to one drop in an Olympic-size swimming pool! Whilst very impressive, it is certainly not the same as one drop to the entire ocean.

Sharks’ nostrils are located on the underside of the snout and are lined with specialised cells that comprise the olfactory epithelium. Water flows into the nostrils and dissolved chemicals come into contact with tissue, exciting receptors in the cells. These signals are then transmitted to the brain and are interpreted as smells. It is the extreme sensitivity of these cells and the enlarged olfactory bulb of the brain that assists the incredible smelling-ability of these creatures.

12. Sharks are better dead than alive. False

Sharks play an integral role in sustaining the balance of the ecosystem. As apex predators, sharks maintain the order of the oceanic food chain and act as an indicator for ocean health by indirectly culling the weak and sick. Sharks also help protect the diversity of other sea-life species by preserving the balance with other competitors.

Additionally, sharks shift their prey’s spatial habitat which consequently alters the feeding approaches and diets of other species. Through this spatial control, sharks inadvertently maintain the seagrass and coral reef habitats. The decline in shark numbers has generated a decrease in coral reefs, seagrass beds, and the loss of commercial fisheries.

Furthermore, without sharks, the number of other large predatory fish increase which feed on herbivores. A decrease in herbivores equates to an expansion of macroalgae which is overwhelming to coral and would shift the ecosystem to one of algae-dominance, affecting the reef system’s survival.

Oceana July 2008 report, ‘Predators as Prey: Why Healthy Oceans Need Sharks’.

13. When faced with an attacking shark, hitting it on the nose is the best option. True!

Whilst it may seem daunting, experts say that the best thing to do if a shark is about to attack is to hit it back!

- If an attack is imminent:

The ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research recommends you defend yourself with whatever weapons possible, “Avoid using your [bare] hands or feet if you can avoid it; if not, concentrate your blows against the shark’s delicate eyes or gills”.

The shark’s nictitating membrane, a protective eyelid-like barrier, is designed for protection against thrashing fish - not a human finger. The eyes and the gills are the most sensitive area for a shark, which also makes them the most effective place to distract and impede an oncoming attacking shark. - If a shark manages to get you into its mouth:

Be as aggressively defensive as possible. ISAF’s George Burgess states that, “‘Playing dead’ does not work”. - If you are bitten:

Try to stop the bleeding and leave the water as soon as possible. Whilst many sharks will not bite again, a second attack is not impossible.

How to help a victim of a shark attack:

- Remove the victim from the water as soon as possible.

- Control the bleeding by pressing on pressure points or applying a tourniquet.

- Keep the victim warm by wrapping them in a blanket.

- Call for medical help and try not to move the victim unnecessarily once out of the water.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2005/07/shark-attack-tips/