New insights into the pink cockatoo, an outback Australian icon

Scientists have undertaken the first genetic assessment of the pink cockatoo, providing insights into how the species has evolved in the harsh inland regions of Australia and how we can conserve this Australian icon.

The pink cockatoo (Lophochroa leadbeateri, also known as Major Mitchell’s cockatoo) is one of Australia’s most iconic bird species. It is a stunning species; both males and females displaying soft pink-white plumage and a distinctive bright red, yellow and white crest. Referring to this bird, Major Sir Thomas Mitchell (1792-1855) wrote, “Few birds more enliven the monotonous hues of the Australian forest than this beautiful species whose pink-coloured wings and flowing crest might have embellished the air of a more voluptuous region.”

Photograph of a pink cockatoo (Lophochroa leabeateri leadbeateri) at Mt. Hope, NSW.

Image: Corey Callaghan.© Corey Callaghan.

Pink cockatoos are found in low densities across the arid and semi-arid inland of Australia, surviving in some of Australia’s harshest habitats. They eat seeds from a variety of plants, including some exotic agricultural and noxious species, and supplement their diet with insects. Like some other parrot species, they are very long-lived – a captive pink cockatoo from Brookfield Zoo, USA, recently passed away at the age of 82!

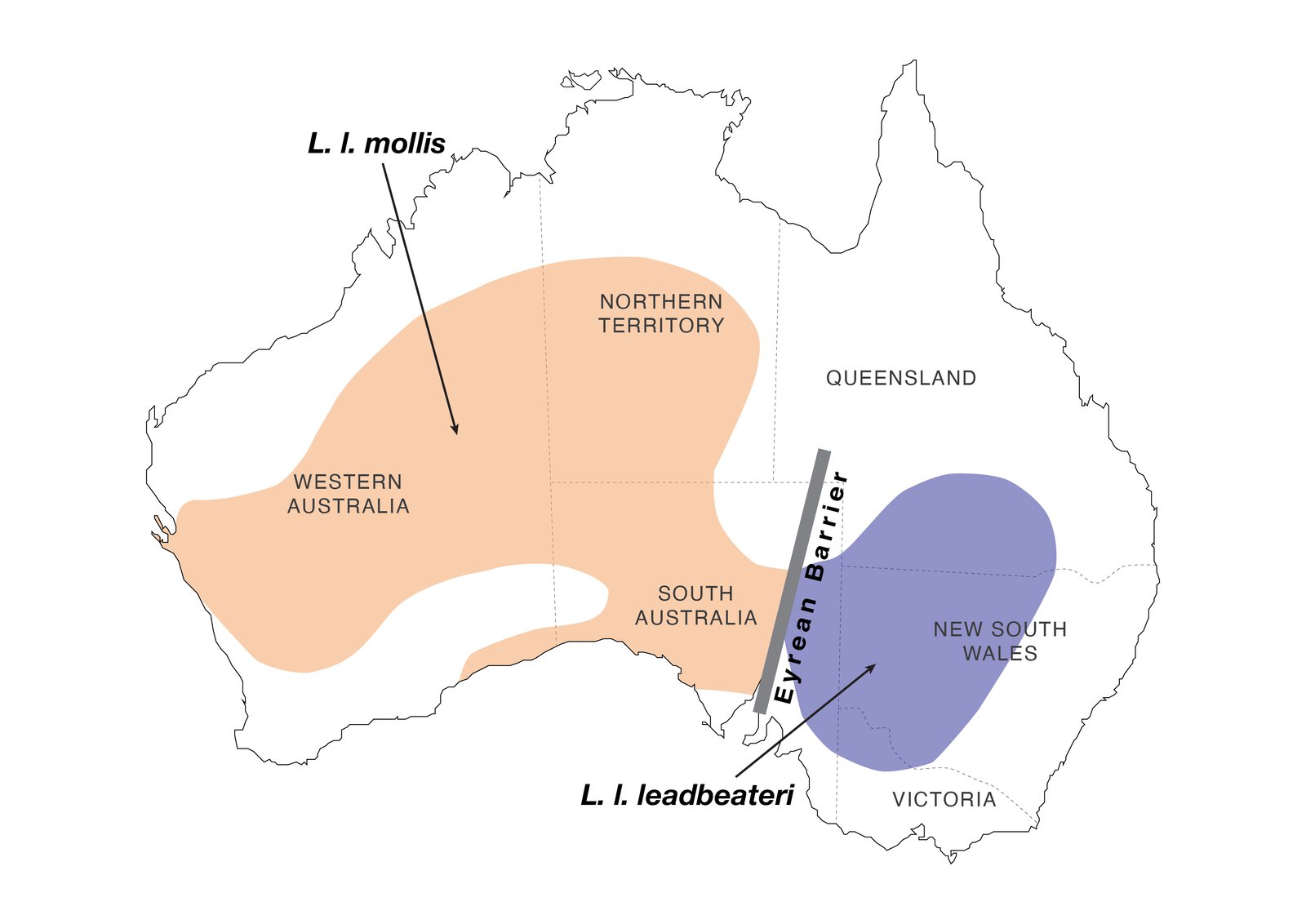

The pink cockatoo is divided into two groups (i.e. ‘subspecies’): one in the central/western part of its range (L. l. mollis), and one in the east (L. l. leadbeateri). These two groups differ in their appearance – birds from the eastern group are slightly larger and have a more prominent yellow band in their crest. These two groups have been recognised as subspecies for over two decades. However, in the past, up to four different subspecies have been recognised. There has been no genetic research to clarify the two currently recognised subspecies or to determine whether they are evolutionarily distinct. Additionally, the pink cockatoo is under threat in some parts of its range, largely due to the removal of hollow-bearing trees, upon which this species relies for nesting. The species is also poached from the wild for the illegal wildlife trade. The beauty and intelligence of this bird makes it sought after as a pet around the world.

The distribution of the two pink cockatoo subspecies. This Figure is adapted from Figure 1A in the associated paper (i.e. Ewart et al., 2021) using Adobe Illustrator.

Image: Figure is adapted from Figure 1A in the associated paper (i.e. Ewart et al., 2021) using Adobe Illustrator.© Figure is adapted from Figure 1A in the associated paper (i.e. Ewart et al., 2021) using Adobe Illustrator.

To better understand the evolution of the pink cockatoo and help improve its conservation, we undertook a genetic study of the species across its entire range. We were able to generate genetic data from over 50 pink cockatoo specimens held in museum collections throughout Australia, including many from the Australian Museum and the Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO, Canberra.

These genetic data support the presence of two pink cockatoo subspecies, as predicted from their morphology. This is seen in genetic differences between birds to the east and to the west/north of the ‘Eyrean Barrier’ region, which comprises the Flinders Ranges and Lake Eyre Basin. The Eyrean Barrier has likely limited the movement of birds between the two areas, leading to reduced gene flow. When gene flow is obstructed, genetic differences accumulate in the isolated groups, which can lead to the formation of different subspecies, and even species. However, we found that the genetic differences between the two pink cockatoo subspecies were relatively minor.

Importantly, we found parts of the pink cockatoo range which had lower genetic diversity. Management of genetic diversity is crucial to minimise inbreeding and to ensure the species has the genetic capacity to evolve to changing environments in the future. In addition, we identified a panel of genetic markers suitable for wildlife forensic applications for the pink cockatoo, an important tool to investigate trafficking crimes involving this species. These markers can be used to perform ‘provenance testing’, to identify from where birds have been poached, and ‘parentage testing’ to determine whether a bird has been legally captive bred (and not poached from the wild).

This comprehensive genetic assessment of one of Australia’s most charismatic but relatively understudied parrots, the pink cockatoo, has increased our understanding on its evolution, and provided a basis for effective conservation management for this species.

Kyle Ewart, Research Associate, Australian Museum Research Institute; and Postdoctoral Research Associate, University of Sydney.

Acknowledgements:

This study was a collaboration between the University of Sydney (Nathan Lo), AMRI (Rebecca Johnson and Greta Frankham), CSIRO (Leo Joseph) and the University of Edinburgh (Rob Ogden). This study would not have been possible without samples and support from the Australian Museum, Australian National Wildlife Collection, Western Australian Museum and Museum Victoria.

Further information:

- Ewart, K. M., Johnson, R. N., Joseph, L., Ogden, R., Frankham, G. J., & Lo, N. (2021). Phylogeography of the iconic Australian pink cockatoo, Lophochroa leadbeateri. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blaa225.