Patricia Egan: Stories from the Photographic Archive

"As I searched the documentation, held negatives up to the light, trawled through copy prints I became intrigued by what the photographer unintentionally captured..." Patricia Egan

Digitisation specialist Annie Breslin spent time with former Australian Museum archivist Patricia Egan to learn about her favourite and most memorable images and the stories they tell about the history of the Australian Museum.

Interview with Patricia Egan

You worked as an archivist at the Australian Museum on which dates?

PE. 2007- 2022

Tell us how and why you became interested in the photographic collection?

PE. The Australian Museum Photographic Collection was an essential tool for me to mine to answer researcher’s question. As the Museum was an earlier adopter of photography it’s a unique and vast collection spanning nearly the Museum’s entire history and records all the various functions of the Museum from research, education, exhibitions through to marketing and of course the passionate people who brought it all together.

The Photographic Collection compromises images taken and registered by Museum staff as well as donated and purchased Collections though initially for me it was a mysterious medley of images.

The challenge was to “think like the cataloguers” and attempt to identify the contextual aspects of the images to be able to locate the one image I wanted in this large collection. As I searched the documentation, held negatives up to the light, trawled through copy prints I became intrigued by what the photographer unintentionally captured. It seemed like every search had a ‘wow – that’s interesting’ moment.

What do you perceive is interesting and unique about the role of photography in a museum?

PE. No museum in Australia has a photographic collection of the breadth and age of the Australian Museum’s Collection. And unusually for many museums the Australian Museum Photographic Collection has only been housed on one site, has not experienced calamitous events and the original order has been maintained by initially the Photography Department and later by the Archivists.

When a museum has onsite photographers, the staff are involved in recording the day-to-day machinations of the museum and so Photography Department staff might record the lowering of a whale skeleton from a ceiling and its disarticulation. When it’s rearticulated for display decades later, staff can view these important images to ensure the skeleton is correctly and with minimal bone impact brought again to the wonderment of the public.

We see images of what was – maybe a specimen that deteriorated beyond conservation; what might have been – models of buildings that were not built and discontinued specimen collection practices.

Our society is all the richer for the Australian Museum recording its challenges, successes and failures.

Below are Patricia Egan's top five photographic images stories from the Australian Museum archives.

One Tree Island

© Australian Museum

Everyone has heard of the challenges facing the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) with global warming and many people have heard of the vital research conducted by Australian Museum and other renowned marine biologists and ichthyologists on the Reef, but not many know of the Museum’s initial foray into establishing a GBR research station.

Marine biology and ecology have always been Dr Frank Talbot’s passion. So, soon after his appointment as Australian Museum Director in 1965 it was natural that he would want a research base on the GBR.

The accompanying aerial photo helps us understand why One Tree Island was chosen for this center. It is a true coral island seemingly bare, with encircling reefs that provided access to corals formed by the pounding of strong ocean waves and those growing in the calm lagoon.

Field studies commenced on One Tree Island in 1966. It started with temporary structures of tents with a “toddler’s paddling pool filled with fishes being marked before return to the water”[i] which was quickly followed by a permanent base. Despite the numerous studies that were conducted there was a growing awareness of the research limitations due to the cooler waters of this southern reef island.

Due to the generous donations of Americans Henry & Peggy Lomas the Museum established another GBR research station on the more northern, Lizard Island in 1973, eventually handing over management of the One Tree Island facilities to Sydney University. Lizard Island continues to be a flourishing, hive of research for national and international researchers as well as Museum staff but without the research anomalies that were seen at One Tree Island.

One Tree Island reminds me that the Australian Museum was led for a decade by a passionate marine scientist, an early proponent of man-made climate change and sought to broaden the integrity of staff research with stable facilities that could also pursue longitudinal investigations and when the first place was not fit for purpose Talbot worked to find a better location.

- [i] Talbot, Frank “Expedition to One Tree Island”. Australian Natural History Vol 15 No 11 1967

Light Fittings in the Long Gallery

© Australian Museum

When the Long Gallery was renovated in 2015 designers sought to evoke the ambience of the Australian Museum’s first gallery and with an eye to the past, the designer asked about the early light fittings.

Of course, the original roof and lighting (gas fittings) had long gone when the ceiling was raised in the 1890’s extension. So what lighting was appropriate?

This seemingly irrelevant photo was taken to document Museum staff installing the new Invertebrate display in 1959 and reminds me of the complexity of archival research that cannot always be undertaken by a straightforward database subject search but rather involves contextual investigations of many records.

Whilst the photographer who catalogued this photo understandably noted the subject as “Galleries Invertebrate Tree under construction” the photo answered the architect’s question as here was a clear image of old light fittings.

But there’s more to this photo which is dominated by the ceiling in what can only be described as a confusion of panels and shadows. Delve into this and we discover the Museum’s relentless search to obtain a balance between bright lighting for visitor enjoyment and the need to block sunlight to enhance specimen preservation and safeguard against humidity increases exacerbated by constant ceiling leaks.

Are these the chandeliers installed in 1940 in the North Wing [further complicating the research - this gallery has had various naming iterations over the years] or was new lighting added during the repairs that followed the severe hailstorm in 1947 or after a new copper roof was approved in 1955? By the 1970’s these lights are no longer visible in photos leading us to speculate they were removed during 1960 – 1961 when the Long Gallery skylight was removed and artificial lighting upgraded in the Invertebrates Galleries.

The next time you visit the Westpac Long Gallery glance upwards and admire the light fittings that mimic these earlier light fixtures and the symmetrical ceiling, the solution to the previous climatic challenges.

The Parkes-Farmer Building and Dr Evans

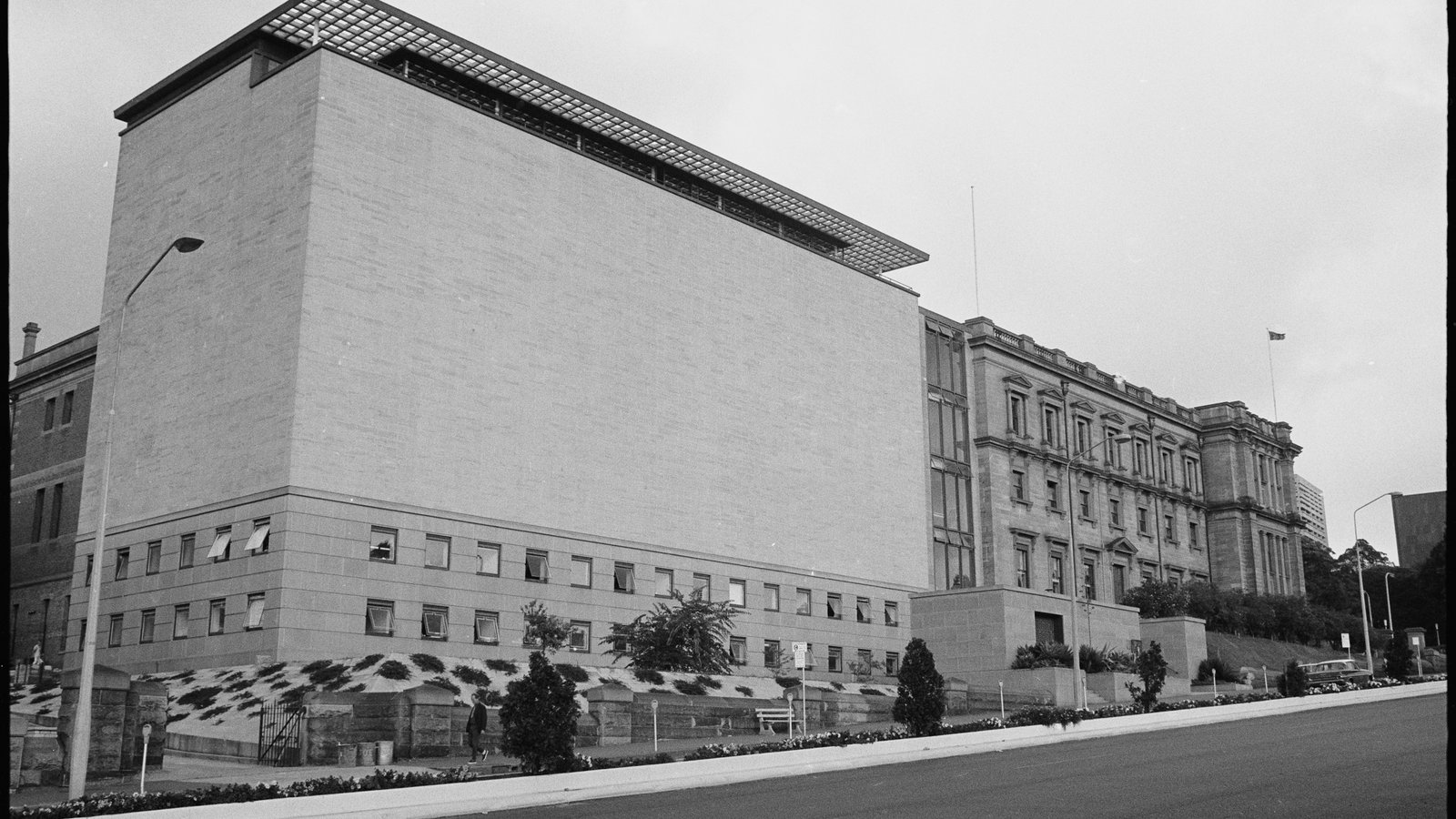

The appeal of these photos for me is how one man’s quiet tenacity had a significant impact upon the Australian Museum’s innovation and growth. These two photos show what we now take for granted but how at the time was of great significance in the history of Australian museum construction.

On William Street is an imposing windowless sandstone façade that stands in stark contrast to the 1880’s adjoining Museum building highlighting the considerable gap between building additions to the constantly growing Museum.

When Dr John Evans arrived in 1954 as the new Museum Director, he found the galleries ‘overcrowded’ and the exhibits ‘indifferently arranged, poorly labelled, and unlit.’[i] Evans introduced changes to the galleries and exhibits, bringing the Museum into line with contemporary display methods in major international public institutions.

Evans successfully obtained government funds for construction of a new Museum building, the first major expansion since 1910. The completion of the basement and sub-basement in June 1960 meant that for the first time in its history, the Museum had work areas designed specifically for scientists, along with badly-needed collection storage space.

The upper floors of the William St Wing were completed in 1963 and the building was traditionally named after the Government Architects who designed and constructed the building – Cobden Parkes and Edward Herbert Farmer.

Like the first Museum buildings it was also constructed from Hawkesbury Sandstone, though quarried at Bondi, and as it was in complete contrast to the existing structure was joined by a glass stairwell. This stark façade remained until 1974 when a life-sized skeleton of the Australian Museum’s stegosaurus was suspended on the wall and later the first branding of the buildings as “the Australian Museum” was hung in 1977 with the current logo added decades later.

Overnight the floor space of the Museum was virtually doubled. though the lack of windows in the new Parkes-Farmer Wing galleries did not go unnoticed. In 1962 Museum Director, Dr Evans explained “The reason for this lack [of windows] is that most effective museum display is achieved with the aid of artificial light”[ii]. Since then, no gallery has been built with an external window.

In contrast to the vast, badly lit and humidity challenged 19th century galleries, photos of the Gallery of Melanesian Art (opened in 1968) show visitors in the new, modern gallery specifically designed to enhance the visitor experience and minimize harm to the display objects.

- [i] Author unknown, “Dr John William Evans, Director 1954-1966”; Australian Museum website accessed 3 April 2024 https://australian.museum/about/history/people/dr-john-william-evans-director-1954-1966/

- [ii] Evans, John “The New Wing” Australian Natural History Vol XIV No 4 1962

M.1674: A Thylacine specimen

![Thylacine specimen M1674. AMS421/3/p5/[a]. From a black and white photographic print. Date: c1902](https://media.australian.museum/media/dd/thumbnails/images/AMS421_3_p5_a.e2a5735.width-1600.4040cd6.jpg)

© Reproduction Rights Australian Museum

We often forget that when the Australian Museum opened it was the only Museum in the colony and hence had a wider collecting remit. Whilst non cultural and natural history specimens were transferred to appropriate institutions as they opened all the photographs remained at the Australian Museum. Duly catalogued with consecutive numbering and a ‘B’ prefix these were pasted into albums for management and security. These now fading and yellowed photos show an array of images of interest to Museum staff covering topics relevant to the collection along with those such as USA towns of dubious relevance.

Digitisation enhances access to images and connections between the photos. Previously unseen aspects emerge and relationships between seemingly disparate photos are revealed in mass digitisation projects.

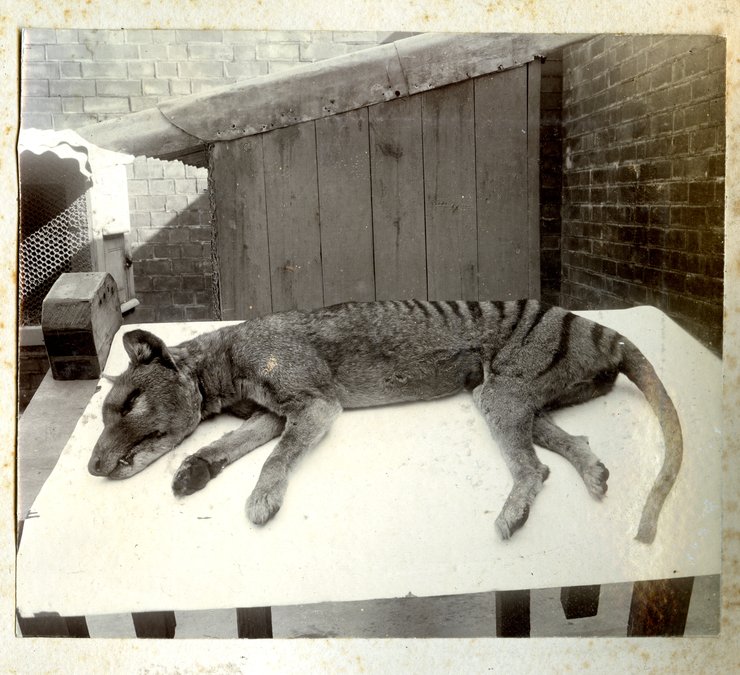

Of interest to me were three uncatalogued photos of a thylacine specimen pasted seemingly randomly into one of the albums. Usually, when the photo related to a specimen or object, that relationship was annotated in the album – but not these photos. Yet, Mammal Collection Manager, Dr Sandy Ingleby, confirmed the stripe pattern (unique to individual thylacines) matched a thylacine specimen in the Mammal Collection, M.1674.

Having the specimen identification allowed the Mammal Register to be searched providing a date – M.1674 was accessioned into the Australian Museum Mammal collection in 1902 and therefore I could read the supporting 1902 correspondence. The letter a working document, that came with the specimen was annotated with administrative comments. Here the basic facts emerge – the “Tasmanian Wolf in flesh”, valued at £5, came on Exchange from the University of Sydney Zoologist, William Haswell, who was also a Trustee of the Australian Museum and noted the specimen would be articulated for display. However, there were no details about where or when the animal was captured.

The hunt was on to identify where the images were taken.

The resolution is clear and precise – these were not amateur photos. In one photo the leg is strung up to show the pouch – the photographer is interested in the animal for its scientific value. The cornering of the brickwork is distinctive as is the cage and wooden lean-to though unfortunately the 7” x 1 ¼” hardwood boards that can be seen were commonly used in Government Buildings.

In 1902 it made sense to photograph a specimen outside in better lighting than indoors, but it could have been at the Australian Museum or the University of Sydney or the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. All of those institutions have undergone major renovations since the photos were taken.

In my attempt to locate further information I was taken along closed corridors and into the depths of the Australian Museum, spoke with ex-staff (an advantage of working in an institution where people work for decades) and consulted staff at other institutions though all to no avail.

But what is clear is that staff of all these institutions worked closely together sharing knowledge, skills and resources and at that time the practice of sharing the taxidermy and the specimens of the increasingly rare but intriguing thylacines was common.

M.1674 is a mounted skin with its skull. The remaining skeleton was sent back to Haswell. This was a mutually beneficial project for both the Australian Museum and the University of Sydney.

The story of the photos does not end here as I also assisted renowned thylacine expert Dr Kathryn Medlock to investigate this animal further and she will soon be publishing her results about the history of this animal.

Next time you wander through the Wild Planet Gallery pause, gaze at M.1674 and reflect upon the fate of extinct animals.

Lantern slides illuminate women artists

Key to Simon Pittard’s appointment as Director of the Australian Museum in 1860 was his experience at public lectures – a focus that continues today.

In 1910, adopting the new projectors powered by electricity brought an immediacy and contextual enhancement to regular educational presentations about all aspects of the Museum’s endeavours. The enthralled public flocked to the lectures. It wasn’t long before lectures geared for children were introduced and Museum staff journeyed to suburban and regional areas to speak.

Although most lantern slides were commercially manufactured, those at the Australian Museum were predominantly produced internally by the photographers – a painstaking and fiddly process. A glass positive was produced by exposing a sensitized glass plate, generally in contact with the original glass plate negative image of a document, photograph, specimen or illustration in a book.

The exposed plate was then developed and fixed in chemical baths before being washed and dried. Sometimes the image emulsion was painted with coloured dyes to enhance the image, and then the emulsion side of the plate was sandwiched between another piece of glass and sealed around the edges with gummed paper tape. This provided a robust object containing an image that could be projected on a screen via a “magic lantern”.

Hand-colouring a lantern slide is a time consuming and expensive process so it was applied selectively. In acknowledgment of this specialist activity the Lantern Slide Registers meticulously record the name of the hand colourist alongside other details.

Taxonomic scientists are often highly regarded for their fine, detailed illustrative skills. At the Museum their skills were complimented by a small but significant number of women artists, often overlooked by the official record because they worked on commission – trained artists who turned their hands at Museum work to make a living. So it was that most of the hand-tinted lantern slides were coloured by Ethel King or Mrs Tom Iredale (nee Lilian Medland) or scientists Frank A McNeill, Anthony Musgrave and Roy Kinghorn.

In 1926 two Museum scientists Ellis le Geyt Troughton and Arthur A Livingstone undertook an extensive nine-week expedition collecting in the Santa Cruz Islands. Upon their return to the Museum 90 lantern slides were made of specimens along with photographs taken on the expedition for the very popular Santa Cruz [lecture] Series presented by Livingstone or Troughton. In fact, it was initially so popular press advertisements noted the lecture was not only repeated but continued to be presented until at least 1931 when Troughton spoke “illustrated with lantern slides and showed the various points of interest on the trip”[i] at the Feminist Club.

Amongst the slides for this lecture is a beautifully photographed large (it is hand-sized) day-flying moth then described as a new species Nyctalemon petroclus though subsequently reclassified as Lyssa macleaya. This magnificent moth is seen in the accompanying lantern slide prepared by Museum photographer George C Clutton and hand-coloured by Ethel King.

By her 20’s Londoner, Lilian Medland, was acknowledged as a highly skilled professional natural history artist. A profession she balanced with her work as a nurse! The demands for her skills continued when she moved to Australia with her husband Tom Iredale. Although employed as a conchologist at the Australian Museum, Iredale continued his expertise in ornithology and in 1927 assembled his highly popular lecture ‘Gould and his Birds’ illustrated not just with lantern slides but also a film. It’s not surprising that Medland was called upon to hand colour slides for the lecture series including this image of Black Swans taken at Centennial Park by P A Gilbert (a talented, amateur naturalist).

So, what’s unique about the Australian Museum lantern slide collection apart from the extensive collection with meticulous slide documentation? The Museum often holds the original photograph/publication, the ‘internegative’ taken of that object, the lantern slide, the order of display with notes for the lecture series along with who presented the lecture and where it was delivered. Some lectures were captured by Museum photographers.

These images allow me to bring the women artists out from the shadows – acknowledging their true place in the history of natural science illustration.

- [i] 1931 'FEMINIST CLUB.', The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), 11 November, p. 6. , viewed 16 Apr 2024, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16816807

Explore Patricia Egan's favourite images

See more photographic collections

Dive into the Australian Museum photographic collections and learn about the Museum's rich history through rarely seen photos.

Discover more

![Black Swans [Cygnus atratus]. Original photograph taken at Centennial Park, New South Wales. Used in a lecture <i>Gould's Birds</i>. Hand coloured by Mrs T. Iredale. Date 1927 AMS164/VV03568](https://media.australian.museum/media/dd/thumbnails/images/ams164_vv03568_c01.fe8c36a.2e16d0ba.fill-1600x900.d69e643.jpg)