Ron Lovatt - DigiVol extraordinaire

Ron Lovatt at a morning tea in June 2023, which was arranged to celebrate his service and skill to the DigiVol program. Prints of his photography feature in the background.

Image: Abram Powell© Australian Museum

Ron Lovatt has demonstrated extraordinary skill, dedication and support over 12 years in the DigiVol program since its inception. He quickly progressed from digitising Entomology specimens to learning new high-resolution imaging skills, which enabled AM Collection staff to have quality images taken of dry insects, fish, marine invertebrates, palaeontology fossils and mammals.

Ron is an award-winning competition photographer and was selected in 2018 to handle and image the Mammals Icon Project’s fragile and valuable specimens. His photography is testimony to his dedication to his craft which has been recognised and appreciated widely by AM Collection staff, with some of these outstanding images being included in the AM’s research scientist published papers.

Ron is currently taking high resolution images of extinct mammals and he continues to generously give his time to mentor and support staff and volunteers to upskill in high resolution imaging of the collection.

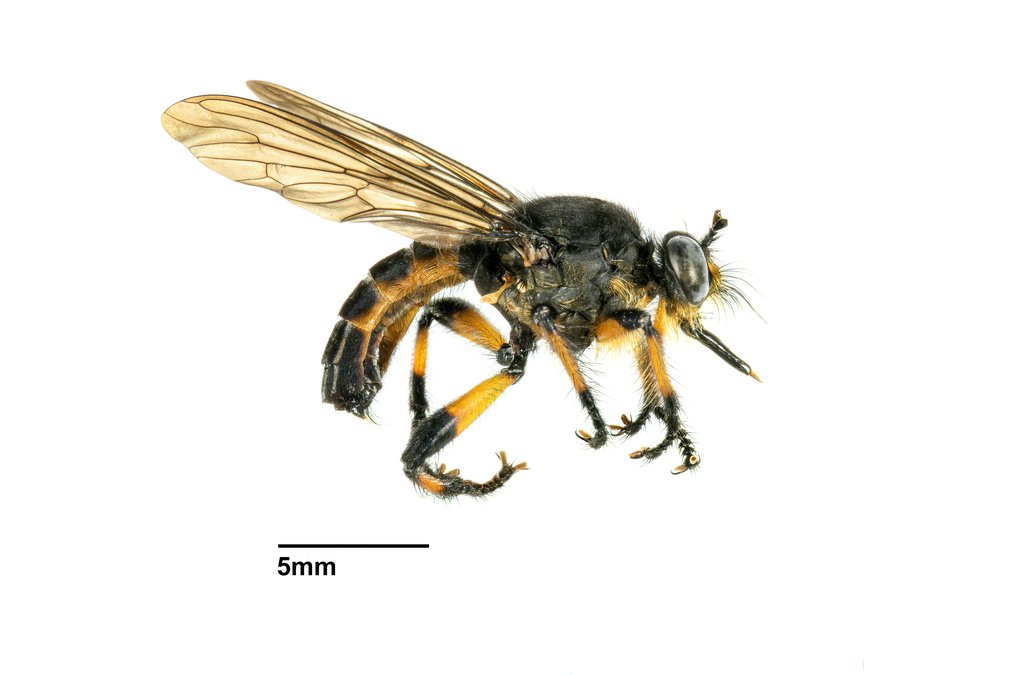

Photography by Ron Lovatt

Most of these images are composites of many photographs - sometimes there are over a thousand composited into one image! A variety of post-production techniques might be used to construct the final image such as focus stacking and image stitching, with some images taking days or weeks to produce. With these final high resolution macro images the viewer can see microscopic details in context with the whole animal. Zoom in to explore the images below.

Listen: Professor Kris Helgen in conversation with Ron Lovatt

Professor Kris Helgen, Chief Scientist and Director of the Australian Museum Research Institute (AMRI) in conversation with Ron Lovatt, the Australian Museum's longest serving 'DigiVol' photographer. In this recording Ron talks about his early years and what prompted him to return to nature photography later in life. He discusses his techniques for producing the ultra-high resolution photography that he employs in the Australian Museum Citizen Science program DigiVol.

Recorded 6 September 2023 at the Australian Museum.

Voice Over: This is an Australian Museum podcast.

Kris Helgen (KH): Well, today we're here at the Australian Museum. My name is Kris Helgen. I'm the Chief Scientist of the Museum and the Director of the Australian Museum Research Institute, and I'm pleased to be here today with Ron Lovatt. Welcome, Ron.

Ron Lovatt (RL): Thanks, Kris. Nice to be here.

KH: Great to have you, and it's great to be sitting down to conversation today. I'm going to give a little bit of background to Ron. Ron Lovatt is our longest serving Digivol volunteer, and in the work he's done with us, he has demonstrated so much skill, dedication, and support to the Digivol program over 12 years. Is that right, Ron, 12 years?

RL: Yep. 12 years this October.

KH: That's just fantastic. And I, you know, Ron came to the museum and he quickly progressed from digitizing entomology specimens, so insect specimens here, to learning new high-resolution imaging skills, which helped enable our collection staff to have quality images taken of a whole variety of things. So that was dry insects, fish, marine invertebrates, paleontology fossils, and mammals. And Ron, I'm somewhat most familiar with your work on mammals in particular.

RL:Exactly. Those are my favorites.

KH: In 2018, Ron was selected to handle an image, the mammals icon projects, fragile and valuable specimens, and this resulted in Ron taking 225 images of specimens. And this required him spending countless hours at home editing these images to a professional standard, a very exacting standard, as you've shown me, Ron. Incredible.

RL: Yeah. I'm a bit of a perfectionist. So that, yes, I spend quite a bit of time making sure that they do look as good as they can be.

KH: Yeah. And they do look good. That quality of this work, these images from Ron, it's recognized, it's appreciated by our collection staff. Some of these images have been included in our museum's research scientists' publications, published papers. And currently, Ron has been taking high-resolution images of some of our extinct mammals.

RL:That's right.

KH: Real treasures in the cabinets. I also want to mention, as we get started, that Ron is an award-winning competition photographer and he's been so generous over the years with his time in mentoring and supporting other staff and other interested volunteers to upskill their talents and skills in digitizing here at the museum. So we thank you for that, Ron.

RL: It's been a pleasure.

KH: Yeah. Well, I want to start our conversation, start at the beginning here. Let's think about the beginnings for you and your childhood. Tell us, where did you grow up and how did that upbringing sort of shape your relationship with the natural world?

RL: I had a very mixed background in as much as I was actually born in Egypt. English and Italian parents. And I started an interest in what was around me. Used to love catching lizards, looking at them and the like. And as I grew older, that became even more so. So I progressed from the love of nature progressed from there. Used to love experimenting with breeding mice and all sorts of things. At one stage, I thought I'd be a vet, but that didn't happen.

KH: Right. And your career took you in other directions?

RL: Yes. I actually went into a trade initially as a woodcarver because I also have an artistic background. Which has helped in what I'm doing with my photography.

KH: Yeah. Well, tell us...So this fascination with the natural world goes deep for you, but how about photography? Where did it start with photography? How did you get into it?

RL: My father used to be quite interested in photography and he bought me my first camera. And all the walls are flicked many, many years ago. So I used that. I never went into the point of actually doing my own sort of developing and the like. But I used to enjoy it. Then I sort of lost interest for quite a while. Then probably about 25 years ago, bought an early digital... Well, an SLR. Then moved over to digital. And then of course started photographing insects around the place and animals and the like. Found I enjoyed that. So that's how it progressed from there.

KH: So your love of nature and the interest in photography combined. Were there some formative experiences with nature photography, things that just like hooked you in and projects that took a hold of you maybe?

RL: Yeah, starting the volunteering work in here gave me more of an interest into insects. That then led me to looking at a couple of websites and individuals, general and by the name of Levon Biss, who's a British photographer who approached the Oxford Museum of Natural History with the concept of doing high resolution images of insects. And I saw some of his clips and his stacking work and thought, hmm, I'd like to try that.

KH:You're going to give that a go.

RL: Yeah. So I started doing that and of course brought that here into the museum.

KH: Yeah. Fantastic, to remarkable effect. I've seen so many of your images and these are images that some of my favorites are not just of some of the many of the specimens that we have here, but work that you've done out in nature, even in your own garden.

RL: Well, I started a project which I called in your garden, basically, photographing every insect I could find in our own gardens where we live and doing them in high resolution to show people that that little bug isn't an ugly little thing, but actually has some real beauty about it and some detail that you just cannot see with a naked eye.

KH: And when I look at these images of yours from your garden, the way this animal is blown up, you know, a small insect, you know, to great magnification and incredible focus. I mean, you might as well be looking at a megafaunal animal. It might as well be an elephant or a giraffe.

RL: You know, you're seeing this incredible detail and it's sort of more on the level with you, you know, as a human being. You know, you could, an insect that maybe measures two or three millimeters. The way I image them, you can blow them up to be a meter or more. And get all the detail.

KH: Oh, they're absolutely stunning. And you can see some of these images I know on our website. And I encourage people to have a look as we're listening, as you're listening to this conversation. So we have been so pleased to have you working here and volunteering at the museum. How did it start with you? How did you first come to be volunteering here?

RL: My wife and I have been members of the museum for many, many years. And before the projects, the DigiVol project started, we received an email saying that they were looking for people who were interested in volunteering at the museum, taking photographs of whatever part of the collections. And as I had the interest in photography, I sent an email back in saying, yes, I'd like to get an email back saying what days could you be available? I gave them a list of days and the rest is history.

KH: And we've had you here ever since, which has just been fantastic. So yeah, with the 12 years you've been here, what's it been like watching the kind of museum change and unfold? What changes have you noticed? What have been some favorite moments?

RL: Well considering the way the first setup we ever had when we started digitizing how primitive it was that we used to have to run up and down the stairs to focus the camera. And then when we had a batch of photos, we'd take the SD card, put it in a computer and download them onto the computer to the setups we now have. It's taken a while to get there, but working on some of the collections has been really interesting. When I did the butterfly collection a couple of years back, from one of the donations, there was something like 400 cases of butterflies from somebody's private collection. His name actually slips my mind, but that was really interesting to see these beautiful butterflies. The ICONS project obviously has been very interesting and I've learned a hell of a lot doing that.

KH: Yeah, well we've been thrilled to have you on that ICONS project. That Mammals ICONS project features some of the most sort of notable and famous mammal specimens in our collection, type specimens, those that formed the original basis for scientists naming some of the species from Australia and Pacific for the first time and some of our really unique and extinct animals. So you've seen so many of the treasures of our collections, including the mammal collection. Is there any specimen or species that really stands out as a favorite for you?

RL: Probably because the amount of time I spent in doing the Mammals ICONS and one of my favorite images that I've done is actually one that I believe is close to your heart, which is the sheathed bat from New Guinea.

KH:Yes, yeah, absolutely.

RL: I mean that specimen was collected in the late 1800s and it's an awesome looking creature and the different angles I had to take of it to try and show the best parts of it. I really loved working on that specimen.

KH: Yeah, yeah, there's some real special ones there and I'm a big fan of that work that you've done on profiling some of those bats. Some of these bats are stored in alcohol. They're coming out of a fluid jar and they can look a little misshapen to the people that aren't familiar with the way specimens are stored. But you were able to somehow capture that specimen in a way that does make it approachable and does keep it in exquisite focus. How do you do it?

RL: When I was first asked to do the project and they said there's going to be what are classified as wet specimens and they said, you know, we'll just take them out of the ethanol and we'll photograph them and I said, well, you're literally going to be looking at a drowned rat. That's what it looks like. You're going to get no information out of it at all. So my concept was to try and photograph them still within the ethanol. But because of the fact that they wanted all different angles, I then had to develop special stands to hold the specimens in the ethanol at the angles that they wanted to show different features of either the snout, the ears, whatever it might be. So that was a learning curve for me as well because I'd never done submerged specimens. We talked about doing soups of insects, but nothing as big as a bat or even rats and the like. So it was trial and error.

KH: Trial and error. You were breaking new ground. We don't usually see, you know, people approaching those fluid specimens with the amount of care and dedication and sort of emphasis on getting an art level image coming out of it. That was fantastic. You've been so involved with the DigiVol volunteer program. And I want to remind our listeners that DigiVol is a citizen science online platform where members of the public can come and participate. We have many volunteers that are here physically and that are coming in-house and participating like Ron has done in imaging or helping us with other aspects of getting data for specimens more accessible, the registration data, the scientific background and context, and some of the images of various kinds. So Ron, you've been so invested and involved in DigiVol in a way that I appreciate because you know, our collection traditionally, you had to come and see them in person if you really wanted to do the scientific work on them, right? You had to get in there physically in the building, find your way into the room, unlock the cabinet or find the jar on the shelf. What you're doing is extending and making the specimens available to so many more people. So that's a fantastic thing. Also that work that you're doing is contributing to science and publications, you know, so both from museum scientists and visitors. Is there anything that stands out in your mind as some of the contributions you have made to scientific projects or the scientific literature?

RL: Well as you mentioned, yes, I know that quite a few of my bat images have been in publications. There was a series of dragonfly images I did that were used to be sent off to Europe to possibly identify the dragonfly as a new species. And I had a scientist come out from Canada who was interested in seahorses. And we apparently had a collection of little tiny seahorses from the Red Sea that he'd never seen before and he thought were a new species. So he actually sat with me for a day asking me to take images at different angles of these specimens and then took the images back to Canada with him to then write a paper as far as I'm aware. So from that point of view, yes, the images get used a lot rather than handling the actual specimens.

KH: Right. And that has to be rewarding for you personally to see them being used in that way and then knowing that that investment of your time has led to this resource being all that more accessible and more useful to science. So now I want to thank you, Ron, for the generosity of your contributions that you have made and the remarkable skill and care that you bring to imaging these specimens in our collection. Things like the discovery of new species of dragonfly or seahorse. These are things that are still happening in a museum like ours all the time. And it's work like yours that makes it all the more possible. Thank you for your generosity and your work here, Ron.

RL: It's been my pleasure. And I've really enjoyed it. And I hope to keep doing it.

KH: Thank you.

RL: Thank you.

Voice Over: This has been an Australian Museum podcast.

Macro photography explained by Ron Lovatt

Macro photography is images taken at a ratio of 1 to 1, while Extreme Macro is images taken at a ratio of 2 to 1 or greater. My images are mostly Extreme Macro in the range of 2-4 to 1.

The depth of field in macro is very small and to obtain the detail in an image I use a process called stacking in which I take multiple images at varying sequential focus points just like slices through a loaf of bread. Depending on the subject, a stack may range in size, anywhere from 50 to 1500 images and can take up to two hours to photograph. This is done using a motorised focus rail that moves the camera in increments as small as less than half the diameter of a human hair.

Once the images have been taken, the next step is to merge them all into a single image using software such as Helicon Focus. The finished stack is then processed using Adobe LightRoom and Photoshop to adjust levels and clean the subject, taking anywhere from 5 to 48 hours. For larger subjects, these are photographed in panels, creating a panorama.

Become a DigiVol volunteer

DigiVol volunteers complement the work of collection staff and research scientists by capturing images of specimens, objects and archival materials and then recording label data into digital form. This work helps us to better understand, manage and conserve our precious biodiversity.

Learn more