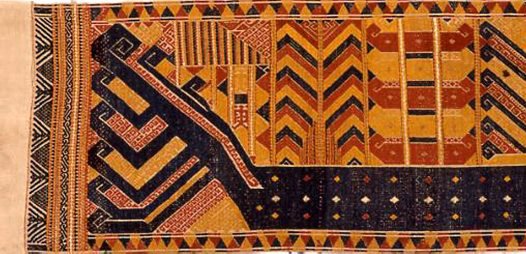

Our Global Neighbours: A Ship Cloth in Life Cycle Transitions

Ship symbol in Lampung helping safe passage from one stage of life to another.

© Australian Musuem

Our Global Neighbours is a blog series containing stories from and about cultures around the world.

Ship motif, often combined with architectural structures, people and animals has a long history in Southeast Asian ceremonial life, extending to the bronze and even Neolithic period.

Ship cloth palepai that could reach over 3 metres in length is the most spectacular example of ship symbolism in textile. Typically dominated by deep blue, reddish-brown or yellow, such woven images with elaborate ships, people, elephants, horses, birds, fish, turtles, banners, bells and umbrellas were made in the areas of Semangka and Lampung bays in southern Sumatra.

Relevant information is scarce because the massive tsunami that resulted from the eruption of nearby Krakatau volcano in 1883 devastated the entire south coastal area. The physical destruction may have obliterated some earlier customs and it appears that no palepai have been woven since the beginning of the twentieth century. Thus, only a limited number of these impressive hangings exist – it is estimated up to about 1,500 are in various private and public collections.

From the sixteenth century Lampung was ruled by the Banten Sultanate, which became the largest pepper exporting power in Southeast Asia. Lampungese were the major suppliers of pepper and obliged to ship the crop to Banten Port. Lampungese men were required to plant and maintain pepper trees - 500 for every single and 1000 for every married man. They were not only at the vital maritime trading junction, but also essential players in the creation of wealth passing through Sunda Strait. This wealth soon brought Portuguese merchants, then followed by the Dutch.

It is not surprising that an elongated and intricately woven ship-cloth palepai implies wealth and power. But this symbolism was enmeshed with social rituals and perhaps even related to ancestral devotion. Palepai, unlike other textiles, were especially associated with local leaders penjimbang. While those leaders emerged through some ancestral sanctions as heads of clan-like local groups marga, they were frequently confirmed or even elevated, through payments, as the agents of Banten’s administration.

With the intrusion of the powerful Dutch East Indies Company, administrative arrangements were disrupted and local leaders initially gained relatively more independence, engaging in trade and contraband of their own. Colonial administration needed local leaders to oversee pepper production and collect taxes but increasingly limited their influence and autonomy. Nonetheless, for a long time penjimbang and their families formed an aristocratic class, and one of their privileges was the use of the long ship-cloth palepai.

The palepai is a deeply spiritual and complex textile. The ‘soul’s ship’ is probably a good approximation of its functional importance. This type of cloth is frequently used in ceremonies at various stages of life-cycle when a person transits from one spiritual and social stage to another.

Mattiebelle Gittinger, an accomplished researcher of Indonesian textiles, gives an informative example of palepai use in the marriage ceremony. 'The bride sits before the cloth of her husband-to-be after arriving in an elaborately bedecked procession. This procession has rigidly prescribed positions that may be viewed as constituting a ship form. The bride is thus transported to the marriage ceremony in a ship and finally makes the transition to her husband’s suku [family group] as she sits before his palepai. The ship of the cloth acts as the bold symbol of this transcendental transfer.' And in Sumatra the palepai are also called sesai balak – meaning 'big wall.'

© Australian Musuem