What is a shark?

Sharks are fish that have skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone, making them lighter and more buoyant in water. Over millions of years, they have developed extraordinary senses to help navigate and detect prey.

Sharks are cartilaginous fish

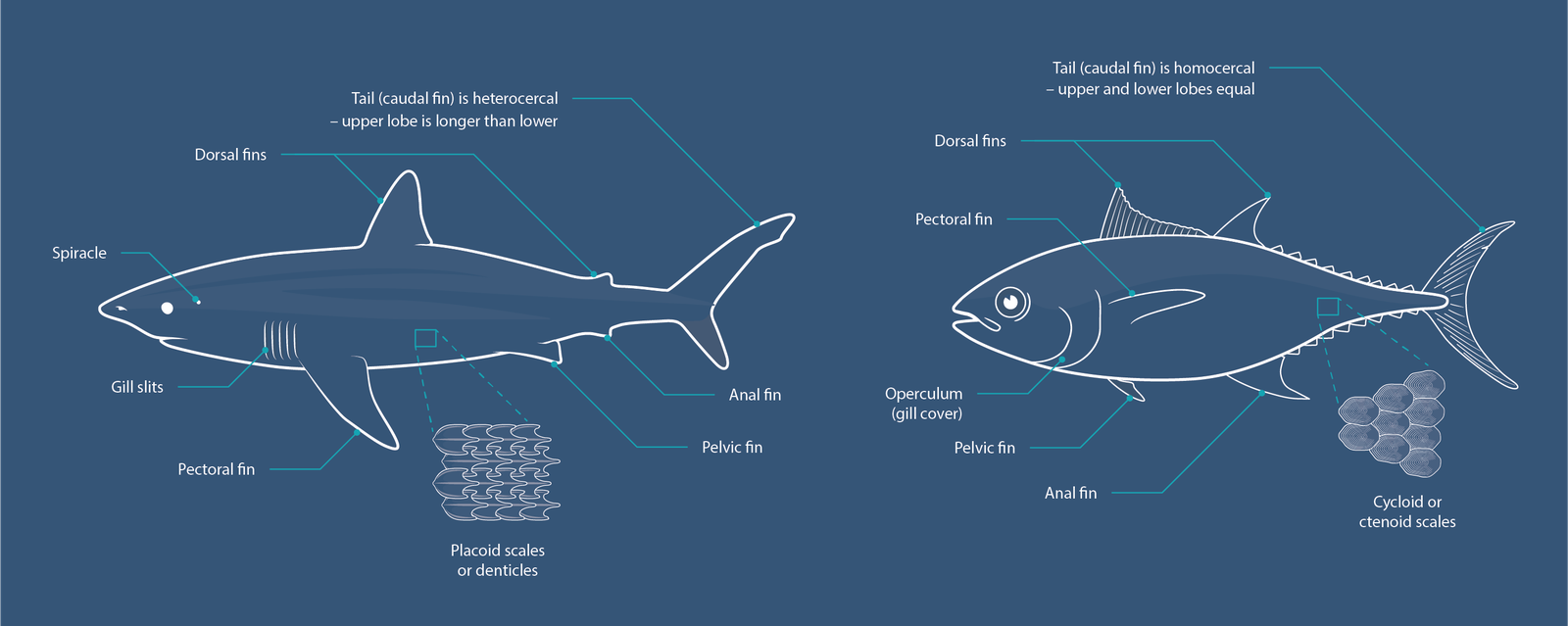

Sharks are fish, but their skeletons are made of cartilage, not bone.

Shark ancestors did have bones, but these evolved to become cartilage, which made sharks lighter and more buoyant. Scales, called denticles, cover sharks’ skin and help streamline their movement through water.

Extraordinary senses help sharks navigate, detect and catch prey, with a mouth full of teeth that continually replace themselves.

This diagram illustrates the main anatomical differences between sharks and bony fish.

Classifying sharks

There are two major groups of fishes – Chondrichthyes (skeletons made of cartilage) and Osteichthyes (bony fishes). Rays and chimaeras (ghost sharks) have skeletons made of cartilage and are related to sharks.

There are 3 living families of ghost sharks and about 23 families of rays.

Shark facts

- There are about 500 species of sharks in the world, 182 of which are found in waters around Australia.

- Almost 40 per cent of sharks found in Australia are endemic – this means they don’t live anywhere else.

- Sharks live in most coastal areas of Australia.

- Sharks live in the Tropics, the Arctic, in very deep and shallow water, on coral reefs and continental shelves.

- Some sharks live in fresh water. A Bull Shark, which can live in salt and freshwater, was found nearly 4000km up the Amazon River.

182 of all shark species are found in waters around Australia.

Image: Australian Museum © Australian MuseumAll shapes and sizes

From the size of a cigar to a large city bus, sharks come in all shapes and sizes.

Whale Shark

Rhincodon typus

The Whale Shark is the world’s biggest fish. It reaches a whopping 12m but eats mostly tiny plankton. As well as filter feeding, it can hang vertically in the ocean, open its mouth and let water, and prey, flow in.

Whale Sharks live in tropical and warm temperate seas, near the coast and in the open ocean. Each autumn, hundreds of these giants gather at Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia.

Status: Endangered. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

Dwarf Lanternshark

Etmopterus perryi

Taking the prize for the world’s smallest shark, the Dwarf Lanternshark reaches just 20cm. It does actually light up. Organs (called photophores) on the shark’s belly and fins produce light to attract prey.

A lighted belly also makes the shark difficult to see from below because of light coming from the surface – handy for evading predators.

The Dwarf Lanternshark is found on upper slopes of the continental shelf off Colombia and Venezuela.

Short-tail Catshark

Parmaturus bigus

One of the world’s rarest sharks, one was collected from the Saumarez Plateau off northeastern Australia in water 590m deep. It’s a holotype – the single specimen that is used to identify all other specimens of a particular species. This 71-centimetre-long female is kept in the Australian National Fish Collection in Hobart.

In 2020, excited scientists on the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor, spotted this 50-to-60cm-long adult male resting on a rock wall 881m deep.

Dr Will White of CSIRO, was part of the virtual science team during this voyage. He is an expert on sharks and identified the species.

Shortfin Mako Shark

Isurus oxyrinchus

Also known as Blue Pointer, Mackerel Shark. Probably the fastest of all sharks, the Shortfin Mako can reach speeds of up to 70km/hr and jump as high as 9m out of the water. It owes its speed to a circulatory system which keeps its body temperature higher than that of the surrounding water. This helps its muscles work more efficiently.

Recreational anglers like the Shortfin Mako because it doesn’t give up without a fight. It has been known to attack boats. Shortfin Makos reach at least 3.5m in length.

Status: Endangered. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

Greenland Shark

Somniosus microcephalus

Able to live for more than 400 years, this is the oldest living shark. As well as being really old, it is very big and poisonous.

Greenland Sharks love cold water, swim really slowly and eat a lot of almost anything. Not content with what’s available in the ocean, these sharks have been found with a polar bear jaw, an entire reindeer, horse bones, and a moose hide in their stomachs.

They also smell. Their flesh is poisonous because of high concentrations of urea. Still, if you boil it in several changes of water or ferment it for several months, then dry it, you’ll end up with Hákarl, an Icelandic delicacy.

The average Greenland Shark grows up to 5m long, but can get as large as 6.5m. They live in the cold waters of the North Atlantic.

Status: Vulnerable. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

Freshwater sharks

Known as ‘true river sharks’, the three known species in the world spend most of their time in freshwater. All are rarely seen and threatened.

These are the Speartooth Shark, Ganges Shark and Northern River Shark. Other sharks, like the Bull Shark and at least three species of whaler sharks, can go far into freshwater. In Australia, Bull Sharks have been found more than 200km up rivers.

The weird and wonderful

Some sharks glow in the dark; some use their tails to stun prey; some are well-camouflaged; others have extendable mouths. They can be speedy or sluggish and live deep in the ocean or in shallow waters.

Video Transcript

The Frill Shark is one of my favourite deep water sharks. It got its name from essentially these really enlarged gill slits that sort of joined here. It looks like a very frilly sort of head shape. From that you can tell that they would live in quite low oxygen environments. But what's impressive with these is these teeth that they have, these three cusps of similar size, but they actually have almost like a quite a prehistoric look.

But they've evolved this eel like body. They're the only shark that has this sort of really elongate body shape. And in the water, they actually swim by undulating the whole body like an eel would. So they've only got a single dorsal fin. Most sharks have two dorsal fins, they've just got the single one, which is situated a long way back, almost creating that sort of paddle, which essentially is used to create that swimming motion that they'd have.

It doesn't have the normal situation around here that you'd see in other sharks. So these are the claspers. So the clasper is a modified part of the pelvic fin, which is what the males use - it's a sexual organ of the males. And they always have two and as they grow larger they calcify, which essentially they get like a hard calcified skeleton within them, which is how you can actually determine whether the animal is mature.

So this species is called the Golden Dogfish. As you can see it's quite a dark colour but when they're caught fresh some of them tend to have a bit of a golden sort of sheen on them, which is where the common name comes from. But this is an example of the sort of colouration you might expect in quite a deep dwelling shark, sort of occurring below 600 meters where there's no light penetrating you get quite dark bodies. They actually can have very bright green eyes when they're first brought up, but they lose that colouration very quickly.

But like a lot of dogfish species, they have these large spines in front of the dorsal fins. This is used as a form of protection against predators. A lot of these dog sharks will feed on mid-water fish, bony fish or fish occurring on the bottom. They can be quite active predators.

One other interesting thing with a lot of these deep water species that actually have quite rough denticles on the body, which is what you see is a scale on a fish, in sharks that have these really reduced scales called denticles, and they assist with sort of hydrodynamic flow. And a lot of a lot of what we know about hydrodynamics for engineering purposes has actually come from the design of the water flow over shark denticles.

So one feature of these dogfish sharks is that actually have a very long abdominal cavity. And inside this cavity they have a very enlarged liver which contains what's called squalene oil. And these large, oily livers sort of provide them with that neutral buoyancy that they need to sort of basically hover and not waste too much energy having to swim around all the time.

This is our Goblin Shark tank. We have two adults and two juveniles in here.

The Goblin Sharks are a deep sea shark, so 1000 to 2000 meters. And one of the things about sharks is that they have an extra sense. They have electromagnetic reception. So what you can see here - see the liquid coming out - they're the extra pores that can pick up electricity underwater.

Of the two specimens we have, one specimen has its jaws naturally set and the other one, we've set the jaws out, which is how the fish catches prey. So it throws its jaws out of its sockets and grabs the prey and swallows it whole.

Epaulette Sharks are one of my favourite sharks, and that's probably because they're the least shark-like of any shark, at least in terms of how we normally think of them.

They're little, typically not more than 75 centimetres in length, and they walk across the bottom of the sea floor. They do that because they're not feeding in the mid-water column like most sharks, on other fishes and things, rather, they're crawling around, poking their heads under coral heads and into the seagrass, looking for molluscs and crustaceans, which is what they typically eat, and they have crushing teeth as opposed to sharp teeth. So just spectacular little animals.

They typically are found in shallow reef flat areas, and in fact, they've actually evolved to be able to walk between tide pools at low tide. So in order to get from one isolated tide pool to the next, you can actually see them walking on land over to the next one, which is just amazing for a shark.

Megamouth Shark

Megachasma pelagios

Guess how this shark got its name? Despite being at least 5.5m long and having a huge mouth, this shark, along with the giant Basking Shark and Whale Shark, eats mainly plankton and jellyfish. When open, its mega-mouth stretches beyond its eyes.

Along with a super-sized grin, this shark has special scales around its mouth to reflect light from the sun or from bioluminescent plankton to attract prey.

The Megamouth Shark was discovered in 1976 near Hawaii. It has hardly ever been seen, probably because it lives so deep, in tropical and subtropical seas.

The Megamouth’s blubbery head, flabby body and large oily liver help it to achieve neutral buoyancy, which means it can stay at a fixed depth without moving much.

Thresher Shark

Alopias pelagicus

Also known as Fox Shark. The Thresher Shark grows to about 5.7m. With a sturdy body and a very long tail fin, it is a powerful swimmer and can leap high out of the water.

Food for the Thresher Shark is mostly small fishes which it rounds up then stuns with its strong tail. Having such an impressive tail can be a disadvantage though – these sharks are often tail-hooked on longlines.

Like the Mako and other mackerel sharks, the Thresher Shark is warm-blooded, which helps it swim faster and be more active. For most of the night, these sharks swim near the surface of the ocean, while days are spent at 300-400m deep.

Status: Vulnerable. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

Zebra Shark

Stegostoma tigrinum

Also known as Leopard Shark.

When young, the Zebra Shark looks like a zebra, but when it gets older it is patterned like a leopard. It grows to at least 2.35m and has a caudal fin (tail) almost as long as the rest of its body.

Status: Endangered. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

Sawshark, Sawfish and Ghostsharks

Sawfishes are commonly mistaken for sawsharks and although there are similarities, sawfishes are actually rays.

Common Sawshark

Pristiophorus cirratus

Also known as Doggies, Saw Dog.

This sawshark’s snout not only looks impressive, it’s also incredibly useful and doubles as a weapon.

The thin feelers on the sides are sensory receptors which detect electric fields given off by small fishes and crustaceans lurking in sediment on the ocean floor. These are flicked up with the tooth-lined saw and eaten.

The sawshark lives in deep water, from 100-630m and grows to nearly 1.5m.

Green Sawfish

Pristis zijsron

Also known as Dindagubba.

It might look like a shark, but this sawfish is a highly modified ray, with gills on its underside like other rays.

One big difference between sawfishes and sawsharks is size. Sawfishes can grow to up to 7m long, while a large sawshark is around 1.5m.

Sweeping their tooth-lined saws (rostrum) to and fro, sawfishes cut down and disable prey. In tactical mode, they’ve been known to swim in pairs, with one killing fish while the other follows and eats.

Status: Critically endangered. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)

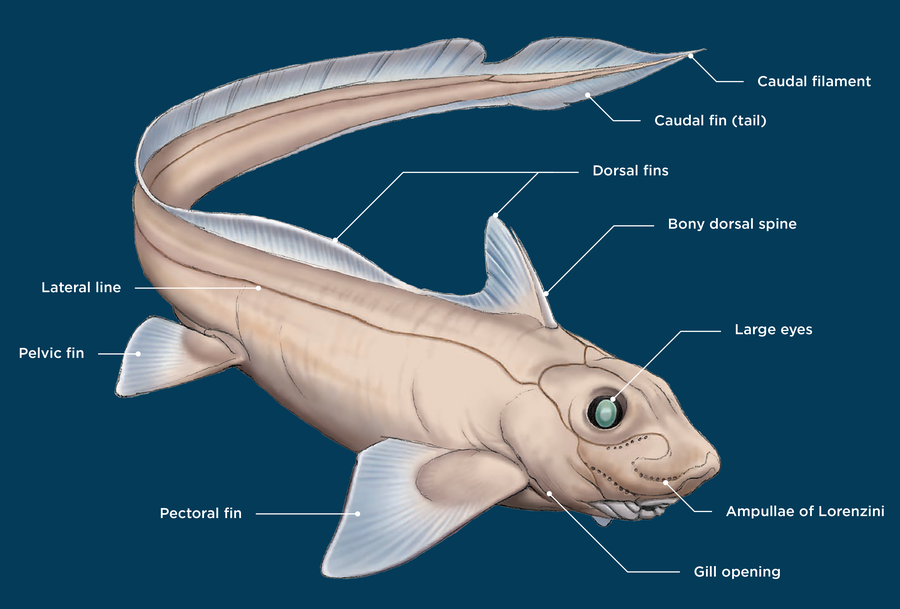

Is it a Shark? No, it’s a Ghost Shark

Ghost Sharks (or chimaeras) are related to sharks, but there are differences:

- Upper jaw is fused to the skull

- Soft, elongated bodies

- Bulky head shape

- One external gill opening (sharks and rays have 5-7)

- Skin is mostly naked (without scales)

- Some species have an extra clasper on the head, used to secure the female for mating

- Most have a venomous spine in front of the dorsal (back) fin

- Large pectoral fins (on the sides of their bodies) used to ‘fly’ through the water

Sharks that hang about

Many deep sea sharks have large livers which make up as much as 30 per cent of their entire body mass. Full of oil that contains low-density squalene, these livers help the sharks achieve near-neutral buoyancy.

This means they can hang nearly motionless in the water, or ascend or descend after prey more quickly than fish with gas-filled swim bladders.