Why oceans need sharks

Apex predators such as big sharks play a crucial role in keeping the ocean’s delicate ecosystem in balance. Intense overfishing has not only had devastating effects on shark numbers but also placed huge stress on the entire marine food chain.

Sharks and healthy ecosystems

As apex predators, big sharks help keep the ocean’s delicate ecosystem in balance.

Sharks keep their prey’s populations in check, which means their prey’s prey is less intensely hunted and the effects continue down the food chain. A healthy fish population means plant life is plentiful, oceans stay healthy and all is well.

Overfishing is devastating shark numbers. As a result, populations of fish and other creatures they eat increase, placing stress on their food supplies, and the whole food chain can get out of whack.

Video Transcript

Predators will usually prey on weak individuals, which keeps them out of the population and keeps the population very, very strong, and therefore keeps an ecosystem strong.

If you don't have any sharks at the top, the layer below them that the sharks are feeding on their population increases. That increase in population, of course, impacts the next layer down. So there's is a cascading effect on the entire ecosystem below.

Animals that are scared of being eaten by sharks actually change their behaviour when those sharks are around to avoid being eaten. There's a really great example on the Great Barrier Reef. When you look down from space, you can actually see halos of sand around the bommies inside the lagoons, and they're created because the herbivores won't go very far from that little bommie because the sharks are around and will eat them. And when you go to reefs where sharks are uncommon, these halos are much larger. And so these fear effects are actually really important in shaping ecosystems, possibly even more important than the direct predation that you see from a lot of sharks.

All of the complex ecosystems we have in the oceans today have sharks in them at one place or another. If we take sharks out of that equation, a lot of these ecosystems would collapse. So for the health of our oceans, for the health of our fishing industries, for the health and diversity of life in the oceans, we need sharks.

It is really important that we conserve top order predators, no matter how scary they are, because that maintains that healthy ecosystem. It ensures that fish stocks are available, which are a food source for us much of the time. And if we destroy that, we destroy our lifestyle, our healthy lifestyle. We can even destroy economies by reducing, by eliminating top order predators.

All the things we have in our ecosystems are there for a reason.

Sharks as ecosystem engineers

Sharks are ecosystem engineers; they modify the ecosystems in which they live.

They are most famous for being apex predators. That’s important, but only a few species of sharks actually fill that role. Just as vital are the sharks that fill the role of mid-level predators in ecosystems. They keep different parts of the ecosystem in check by controlling the populations of their prey.

Understanding trophic cascade

A trophic cascade is like a tall house of cards. Knock one at the top and it’ll knock others below and cause a total collapse.

One example given by Colin Simpfendorfer is from the east coast of the USA, where shark fishing over decades has resulted in large shark populations declining to ‘very, very low levels’. This has meant an increase in prey species, particularly Cownose Rays and stingrays.

This has been hypothesised to lead to declines in things like oysters in Chesapeake Bay because rays eat oysters and scallops. So you've got numbers of large sharks going down, rays going up and the food of the rays going down.

Airborne starfishes

The idea that apex predators regulate and maintain the health of ecosystems has long been understood by First Nations peoples, who regard sharks as guardians.

In science, the idea goes back to an experiment in the early 1960s which involved throwing starfishes out of rockpools. Robert Paine found very large, purple and orange starfishes in rock pools on America’s Pacific Coast. They lived alongside anemones, sea urchins, seaweed, limpets, snails and other creatures. The low tide exposed barnacles and mussels.

Over a period of months, Paine regularly prised all the starfishes off one stretch of rock and threw them out further into the sea. On a nearby site, he left the starfishes alone. Just three months after he began tossing the predatory starfishes, the original remaining 15 species in the rock pool had shrunk to eight.

Over the next five years, without starfishes to keep their numbers in check, mussels took over, pushing all other species out almost completely. On the neighbouring site, the diversity of species remained the same.

Fear factor

Being scary is a good thing when it comes to keeping life in the world’s oceans in balance. As well as eating creatures, sharks scare them into changing their behaviour to avoid being eaten. Colin Simpfendorfer explains:

This is what we call ‘fear effects’ and can lead to dramatic effects in ecosystems. When you look down from space on the Great Great Barrier Reef you can actually see haloes of sand inside the lagoons. They’re created because the herbivores will eat algae in a little ring around their bommie, but won’t go any further because the sharks will eat them.

A bommie is an outcrop of coral reef, often a vertical column.When you go to reefs where sharks are uncommon, these haloes are much larger. This means herbivore numbers are increasing, which affects the reef’s ecosystem.

Ancient ruler

The mighty Megalodon, Otodus megalodon, ruled the oceans millions of years ago. As an apex predator it played an important role in its ecosystem keeping an abundance of large predators, like small whales, in check.

Under threat

We’re making a mess of our planet, putting many species of sharks at risk of extinction. 100 million sharks are killed worldwide every year, putting a quarter of all shark species at risk.

We know this because the world’s largest global environmental network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), keeps track of shark numbers. The situation is serious.

Video Transcript

Using DNA technologies, you can actually amplify DNA from those fins and you can match it back to the animal that it came from in order to pursue whatever research question or in some cases, legal case that you are interested in. Often times when the fins have been removed from the animal itself, it's very difficult to tell what species it came from. And so some species of sharks are actively fished legally, but other species of sharks it's forbidden to fish them - they're essentially endangered and threatened and protected.

So sharks have maybe three choices, I might say, in order to cope with ocean warming, ocean acidification or ocean deoxygenation or any combination of two or three of those threats. They can adapt, move or die.

Sharks have survived the last five mass extinctions. We're probably working on the sixth one right now. You know, the human induced mass extinctions that we're seeing. And certainly what that tells us is that the shark model is adaptable to a wide range of environmental conditions.That's a positive. But in all those other situations, those changes have happened over millennia, not decades, as it's happening now. So it's the rate of change that we're bringing on our oceans currently that is really alarming. Sharks are more in danger from that rate of change because they are such long lived animals, which means a number of generations they have to adapt to change is actually less than something that is much shorter lived and has shorter generation times. So a small fish may have 100 generations to adapt. Sharks may have five or six.

Greenland sharks, 400 years old, don't mature until they're 120 years old. Those Greenland sharks that are born this year, the climate will have changed dramatically by the time that animal dies. And we may already be past tipping points before they're even mature and can have another set of offspring.

Finning is the basic - catch a shark, cut its fins off, it may still be alive, and just toss the body back, keep the fins. Those fins are obviously quite valuable. Used particularly in Asian countries in shark fin soup.

Most of the shark fin ends up in China. China also has huge fleets, and yet China doesn't report shark catches to the IUCN.

Most of the shark finning is occurring in really, really poor countries, and so they're doing it out of need for money, for means of survival. So if there is some way to, you know, I guess redistribute the wealth or we have countries that are that are able to find alternative means to that type of venture, then we can definitely eliminate those types of things.

It saddens me to see this happening and it even saddens me more to go down and see three or four sharks on the bottom, no fins, trying so hard to swim away from Ron and I. They know we're the danger, they're trying to get away, and they're helpless.

Fishing is, by and large the major threat that sharks are facing in the next 10 to 20 years. Yes, there are threats from issues around habitat, climate change, all these things are going to become more important over time, but right now, we're catching too many sharks and there will be a whole lot that don't survive. They will go extinct before they have to deal with these other issues that are coming at a slower pace.

It's that old saying of death by a thousand cuts, and that's essentially what's happening in the ocean. And one of the primary things is obviously our consumption and our take of fish resources, and especially when we develop things like sonars, things like super trawlers. These things are built, designed and they're meant to take out as much as they can.

Threats to sharks

Overfishing, including industrial-scale fishing, is devastating shark populations, according to the world’s largest global environmental network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which keeps track of shark numbers.

Shark finning is a cruel practice and is seriously depleting numbers of some shark species. Our oceans are awash with plastic waste. This kills sharks and other marine animals through choking, strangling and starvation. It also threatens coastal tourism.

Climate change is causing sea temperatures to rise, making some habitats inhospitable to sharks and their prey. The oceans are vast but not endless. Not all shark species can move when conditions become life-threatening.

Industrial fishing

Large-scale commercial fishing is known as industrial fishing. Millions of sharks worldwide are killed by industrial fishing boats every year, even when they are not the target species.

Many of the world’s fisheries aren’t monitored or controlled and surveillance doesn’t happen.

Gear used includes set and drift gillnets and longlines. Drift gillnets can stretch for miles, floating at the surface or near the seafloor.

Once sharks are trapped, they usually die.

As their name suggests, longlines are long fishing lines with thousands of hooks dangling from them. They can extend for kilometres just under the surface, or close to the seafloor.

Hooking mortality is the time it takes for a shark to die once it’s hooked on a longline. For some sharks the survival rate is as high as 95 per cent, for others, as low as 20 per cent. The longer the line is in the water, the less likely sharks are to survive.

Death by Accident

Most fisheries target a particular species of fish. Other fishes, including sharks and marine animals, are caught by accident. This is called bycatch.

In the Pacific Ocean, 3.3 million sharks are caught each year as bycatch on longlines. Sharks are the most significant bycatch species in the world’s major high seas fisheries.

Shark Finning

Shark finning is the practice of catching sharks, cutting off their fins – often while they are still alive – and throwing the body back into the ocean to die. There’s a lucrative market for fins, mostly for use in shark fin soup, which uses dorsal (top), pectoral (side) and caudal (tail) fins.

Finning in Australia

In Australia it is legal to catch sharks and sell their meat, often called ‘flake’, and fins. Shark fins can be imported and exported.

Shark finning at sea is illegal in Australian Commonwealth fisheries. Cutting off shark fins

at sea and dumping the carcass is prohibited.

The ban has greatly reduced the cruel practice, but most fishing in Australia happens in seas managed by the states and territories and not all states have adopted this policy.

Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory do not have ‘Fins Naturally Attached’ (FNA) policies, meaning that illegal live-finning and dumping of sharks is likely to still be happening around Australia’s coasts.

In the Soup

If shark fin soup was taken off restaurant menus, it would save the lives of an estimated 73 million sharks each year.

This soup is a delicacy and a symbol of wealth and respect for many Asian cultures around the world. A bowl can set you back more than $100 AUD. A one kilogram packet of fins will commonly sell for $510 AUD.

Since the Song Dynasty in China over one thousand years ago, sharks have been killed for their fins. Shark fin soup remained a relatively rare luxury in that country until the late 20th century, when standards of living improved and more people could afford to eat it. Consumption of shark fin soup skyrocketed.

However over the past decade, shark fin consumption in China has reportedly fallen by up to 80 per cent. This is largely credited to campaigns calling on people to stop eating it, fronted by celebrities like former basketball star Yao Ming. The Chinese Government has also banned shark fins at state banquets.

Shark fins add texture and have no flavour. Shark fins are usually shredded to thicken and give the soup a gelatinous texture. It is the broth, rather than the fins, that give the soup its flavour. Ingredients can include chicken feet, crab meat, pork fat, dried scallops, abalone, sesame oil, ginger and black vinegar.

Slow Growers

One of the reasons shark populations are vulnerable is because of the way sharks develop and reproduce. Most bony fishes become sexually mature between one and five years. Many then lay thousands of eggs at a time, often several times a year.

But most shark species are slow growing and don’t reach sexual maturity until about 10 to 12 years old. They have long pregnancies, on average between 9 to 12 months, and when they do reproduce, they have relatively few young.

Not all sharks produce young every year. Some take a year or two off after giving birth. This means shark populations don’t naturally grow quickly and they take a long time to recover if devastated.

Oceans of Plastic

An estimated eight million tons of plastic enters seas worldwide each year. Waste plastic makes up 80 per cent of all debris in the ocean – from the surface down to deep-sea sediments.

Plastic joins rubbish dumped from oil rigs and boats to form vast spinning, floating islands of rubbish. Five of these now pollute our oceans. The largest is halfway between Hawaii and California. Three times the size of France, it even has a name – the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Looking just as bad as they sound, these ‘islands’ are harmful to sharks and other creatures which eat or get tangled in the debris. Some die of starvation because their stomachs are filled with plastic.

Figures taken from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

Forensics

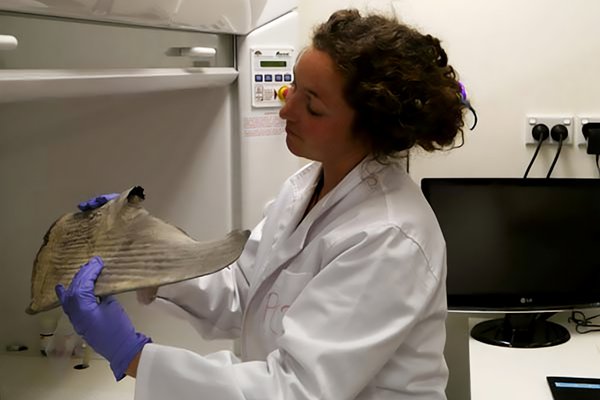

When there is an investigation into a suspected wildlife crime like shark finning, or importing products made from protected shark species, the Australian Museum’s Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics is the first port of call.

As the country’s only accredited wildlife forensics laboratory, it processes evidence in the same way that human forensic labs process evidence in human-victim crimes.

Scientists conduct DNA analyses on biological material to identify species when animal parts can’t be identified visually. In the case of sharks these are usually fins (from fresh to highly processed), but sometimes jaws and other body parts.

Once authorities have a confirmed species, they can then take the next steps in their investigations. If charges are laid, scientists give expert witness evidence in court.

The top threat to sharks worldwide is overfishing; using sharks for their fins, oil and meat.