New South Wales

The warm East Australian Current flows down the New South Wales (NSW) coast, making it a popular habitat for sharks. Discover the stories and ceremonies of the coastal clan groups of the Eora Nation and their connection to the ocean.

New South Wales coast

The warm East Australian Current flows down the New South Wales (NSW) coast, making it a popular habitat for White and Tiger Sharks.

The critically endangered Greynurse Shark also makes itself at home there.

Video Transcript

It's almost like the ocean is a part of me and I am a part of it. I see it as Mother Earth and the ocean is one of our mother's lungs, and it's something that helps clean the carbon and the bad stuff out of the sky and the air, and the ocean being our totem, it's inherently a responsibility for me to make sure that it's looked after and it's cared for.

The land told them. The land spoke to them. And if you say "How does the land talk? How do you understand the land?" And that's what it comes down to. Land doesn't actually speak the same language we speak, you see, that's what it is, it's the same as an animal communicates with an animal. They can hear each other. They can talk to each other. They don't have to speak English or speak the way we speak, but they communicate so they can listen. We built that same relationship with the land, where we could understand what trees saying. We built that same relationship with our animals, where we knew exactly what they were saying. And when an animal tells you how to care for it, that's all you've got to do. You got to follow what it says. When a tree tells you how to look after it, you listen to it. You don't say "No, I actually know what's better for you I know how to look after you. I'll do it this way." You let them tell you. And that didn't come from 10 years. That didn't come from 100 years. It's come from hundreds of thousands of years of learning. From looking and listening.

There's so many different plants that we call calendar plants, or plants that teach us certain things to do at certain times of the year, and that's what it was about. It was about learning what connected with what, and what done what at what time of the year. And once you learnt that, you had to follow it.

When the Mutton Bird is migrating, it's not a good time to be swimming, because obviously you have the younger ones that can't make the journey dropping off and a lot of them wash up into the nearshore area and that's sort of prime taking for something like a Tiger Shark that's an opportunistic scavenger. So that's an indicator that they'd be very active.

When the dogwood bush flowers and seeds, it's another indicator to be cautious and to be careful because sharks are about. Things like after flood events, not swimming because Bull Sharks tend to be more active during those times. When the Jezebel Butterfly starts to migrate up the east coast we know that then the mullet and the taylor or the trevally are starting to migrate north as well. And what follows them are sharks.

As part of the ocean being our totem it's essentially that consideration and that respect for everything that feeds into the ocean or is connected to the ocean, and that includes the land and landform systems. So the whole catchment, the water that comes out of the catchment, the trees that are in the catchment, those animals that are in that catchment, the things that flow down those creeks and down those streams, and eventually everything flows into the ocean. And then in the ocean, the species that are in the ocean, the functions that the ocean does, how it dictates our weather patterns. It's got such a huge role to play on the planet and I'm constantly thinking about the health and the function of all those things. I think that's why I'm feeling a little bit sick and angry. But that's part of my inherited responsibility.

If we're connected to salt water, for example, we have to live and breathe it. We have to come back to be healed with it. It's just who we are as our identity. So where some people would say we're going fishing and we're going to enjoy catching fish for that particular event or day, for an Aboriginal person that's much more of a cultural and identity experience. Knowing that you're fishing at the spot where your ancestors have fished forever, because we haven't come from any other place than here. So it's really our identity. It's the depth of that deep time that we're experiencing. So we're not just experiencing it in 2021, but we're experiencing all of those generations that have come before us. So that's a very powerful concept that the sea is us.

So as Aboriginal people, we also believe that the connection between the sea and the land is one, and it's as far out as you can see to the horizon. But from a European view, the land is most important because you can actually survey it and you can fence it and you can cut it into small portions and then you can sell it. So as you can see, it's just a totally different notion, understanding, that an Aboriginal person has.

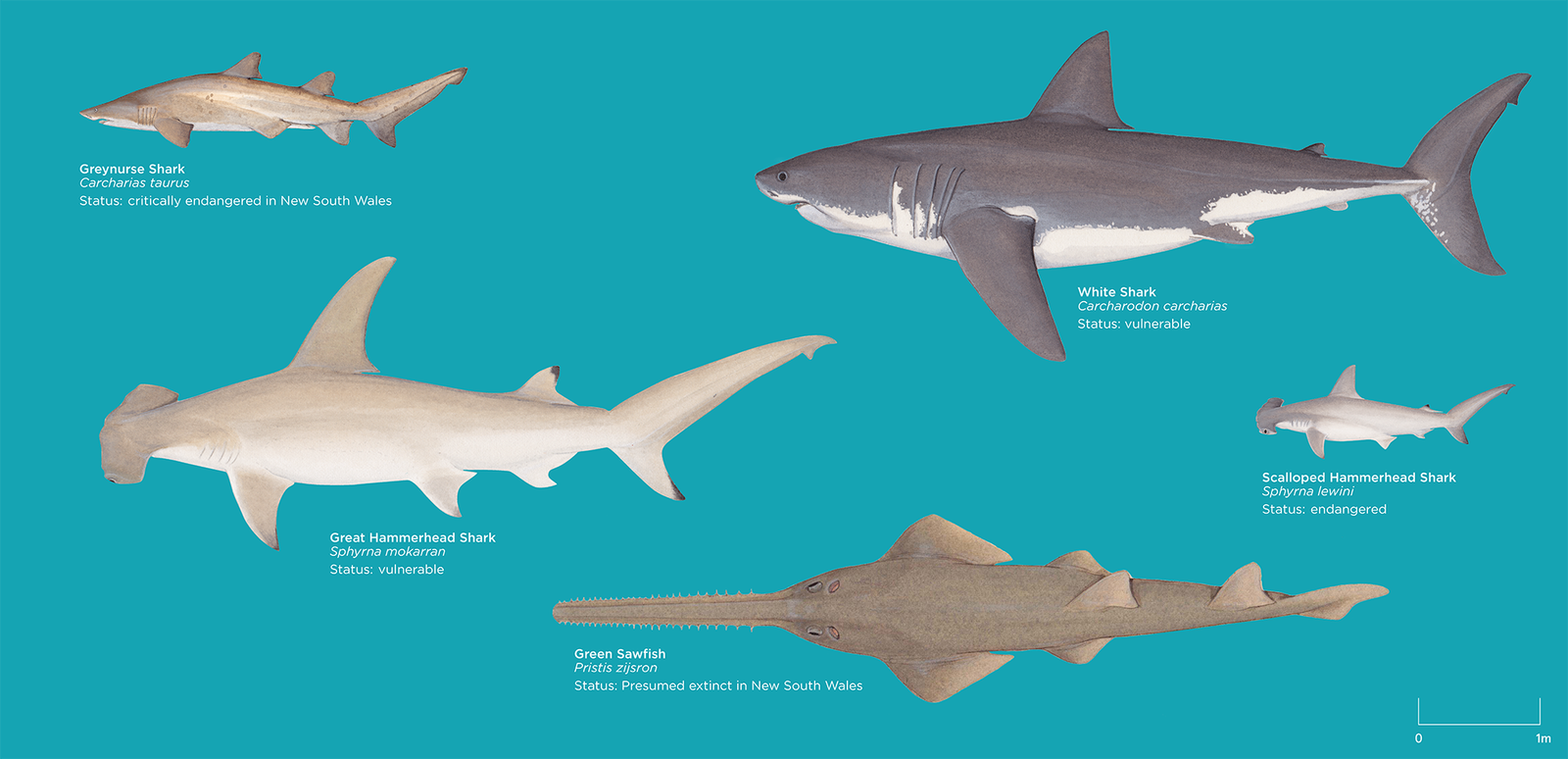

Threatened shark species

The New South Wales, the Department of Primary Industries maintains a list of threatened species as per the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

A threatened species is a plant or animal that has been assessed by the independent Fisheries Scientific Committee and found that they are at risk of extinction.

When the dogwood bush seeds, it’s shark breeding season. The first southerly kicks off the sea mullet migration. When Humpback Whales migrate north and south, sharks trail them. Bull and Tiger Sharks follow the Muttonbird migration.

What’s inside the jar?

It might not look very interesting, but this jar of water, taken from Sydney Harbour, is like a book of stories.

It can tell Joey DiBattista, Senior Research Scientist and Curator, Ichthyology, at the Australian Museum, what’s recently been in the water.

Joey uses Environmental DNA, a new technology that means he can scoop up a jar of seawater, take it back to the lab and essentially isolate DNA from all of the organisms that may have used that environment within a certain period of time.

So we can match it up to all of the different fishes, even some sharks, even going lower to things like sponges and corals that may be in the environment.

He explains that DNA doesn’t last in the environment for very long:

So anything that you pick up is something that's been there fairly recently, within a few hours or within the day.

Eora

The original inhabitants of New South Wales are the First Nations peoples who have been here for 40,000 to 60,000 years.

The Sydney Basin is made up of the homelands of the many clans and families of the Dharawal, Dharug and Yuin Nations. Other NSW clans are the Kuring-gai, Eora and Gundungurra.

The city of Sydney is on the land of the Gadigal people.

Boomerang and shark

Dharawal (cabbage palm) people of the Yuin/Murring are the original people of the Shoalhaven, on the south east coast of New South Wales, and have been living with sharks for thousands of years.

In particular, the Gadhungal murring clan groups the people belonging to the sea. Many of the seasonal camps and majority of life was lived by the sea, Most of the meat caught was from the Gadhu (ocean). The stories and ceremonies of these coastal clan groups have strong association with and deep connection to the marine life. Whales and dolphins are saltwater totems of the area and are ancestors of the Dharawal.

The environment is our church and our religion.

These coastal clan groups interact with the ocean regularly for thousands of years without depleting fish populations or destroying the Gadhu (ocean). Stories passed down from Elders ensured the sea country would remain as is and sustainability was a reality because the customs and rules were followed and elders were respected.

Walimburra is a Dharawal and Dhurga word for the shark. Darlawaan is a Dharawal and dhurga word for Great White Shark. Darlawaan and Walimburra look after Dhalga (old country under the Sea) and Gadhu (ocean).

By watching and feeding, all sharks manage the numbers of schools of Marrah (fish), by stabilising and balancing the amount of grazing done on the weed and kelp beds from fish populations and other marine life.

- Yungah – crayfish

- Djungah – octopus

- Nijilidjong – stingray

- Daringyan – stingray (Dharawal)

- Marrah – fish generic

- dthun – fish generic

This east coast story has been passed down through oral history. Translated into southern Dharawal:

Dhadjamwarri bulla djahdjahlaali yenda bala gadhujaang, mirrir Wallangurraga bulmarri.

Balwa gadhuga bulladeree

djahdjah gummadha walimburrawilia djahdjah

warongiadha daringyanwilia /nijilidjongwilia

Along time ago two brothers went near the sea,

high on the cliffs to fight.

They fall into the sea to die.

Brother with spear become a shark and brother

with boomerang become a stingray.

Joel Deaves, Gumea Dharawal man.

Carved in stone

Possibly the world’s oldest record of a shark attack can be found carved into a flat rock on the sea side of Bondi Golf Course.

The carving, by First Nations peoples, shows an 8m shark that appears to be attacking a figure that could be a human or lizard. It is thought to be about 2,000 years old.

The shark is part of a large panel of carvings in a flat sea-cliff at a fishing rock known to First Nations peoples as Murriverie or Marevera. The carvings were made by chipping into the rock surface with pointed stones or shells.