Mineral resources and environmental impacts

Throughout history, civilisations and empires have been built on mineral resources and they are an integral part of our every day life. However our excessive consumption means reducing our environmental impact is a priority at both global and local levels.

Mineral resources

Our reliance on minerals and rocks has a long history. They provided our ancestors with tools, weapons and wealth. Civilisations and empires were built on them. We now use minerals and rocks at an ever-increasing rate as we continue to build, invent, travel and consume.

Many of the minerals we use every day, particularly metals, are found combined with other elements as ores. These need to be mined and processed to extract what we need. The search for more ore deposits to meet society’s high demand is ongoing.

Our love of minerals has consequences, both good and bad.

Our excessive consumption impacts the environment and changes the climate.

But some minerals hold the key to technological innovations, particularly in the renewable energy sector.

Using minerals

We use and need mineral products every day. Without them there would be no cars, phones or watches. You wouldn't have a house, turn on a light, properly clean your teeth, use a computer or look through a glass window.

This natural wealth comes at a high cost. Extracting and processing ores requires energy often from burning coal, chemicals and materials. Environmental impacts can be extensive and long-lasting. And at some point, these resources will run out.

But there are good news stories. Reducing our impact is becoming a priority at global and local levels. Some minerals are now used in technologies that are making Earth a greener and cleaner place. Which mineral will be the key to our next burst of innovation?

What's in your phone?

Everything you do on your phone requires chemistry. You only need to look at a periodic table to work out why – today’s smartphones contain up to 60 or so elements. Many of these are well-known, such as copper, silicon and gold, but some are obscure elements like scandium, yttrium and neodymium.

We use these elements because their properties enable the many features in our phones, as well as in our televisions, cars, computers and other high-end technologies. Some elements have unique properties that make it difficult to find alternatives, so we need to carefully manage these vital resources for the future

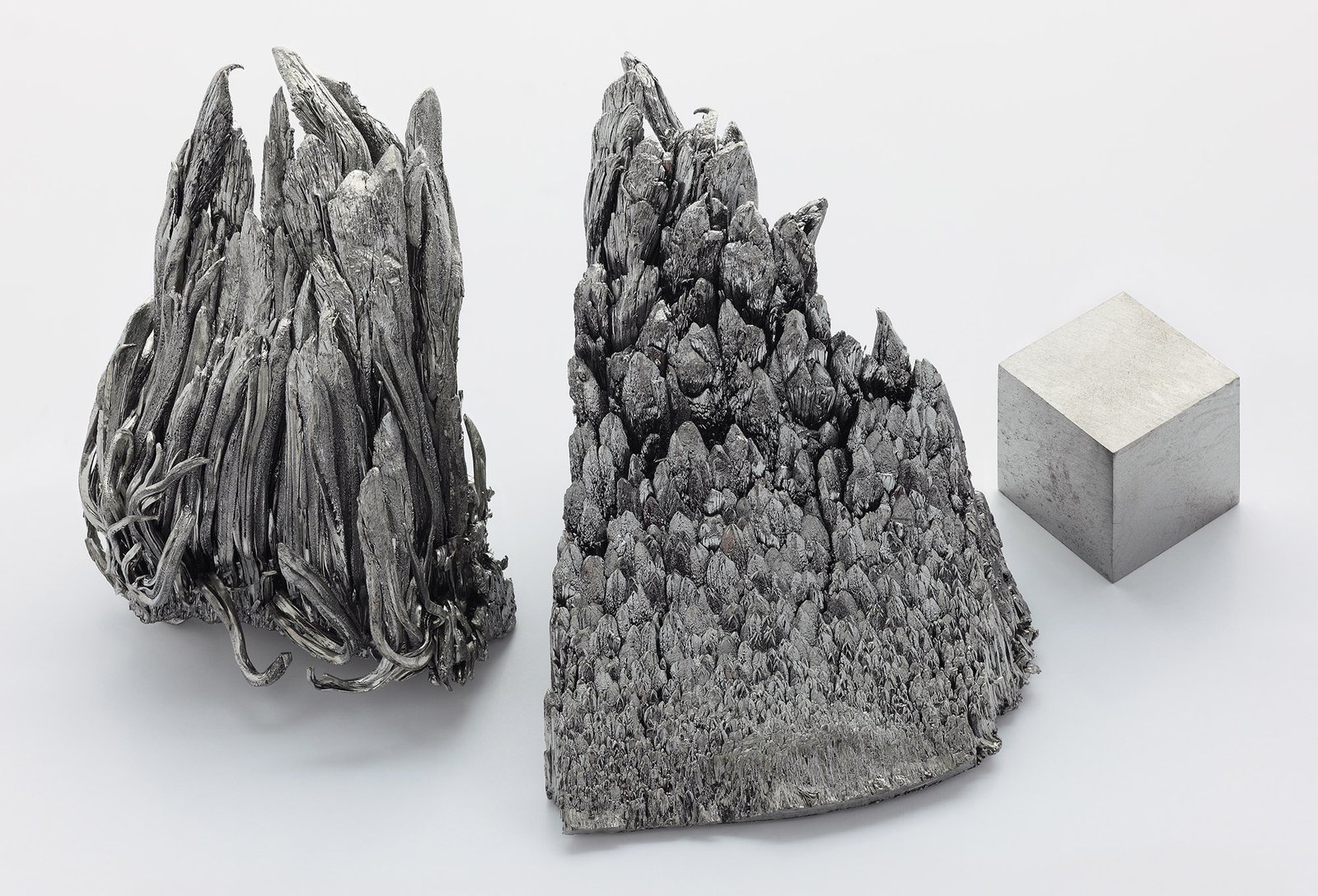

Rare earth elements

Rare earth elements are a group of seventeen metal elements with similar chemical properties – scandium, yttrium and the 15 lanthanides (which often appear as a row at the bottom of the periodic table). They are invaluable for their electronic or magnetic traits, unequalled in other elements. Some are used in technologies, such as wind turbines, solar panels and electric cars, that help make Earth a cleaner, greener place.

Rare earth elements are not necessarily rare in the Earth’s crust but are difficult to extract from the ground or from their ores. Today, China dominates the world’s production and Australia is the only other major producer. The search for new sources is essential and ongoing.

The future of mining

Our discarded electronics and machinery contain literally thousands of tonnes of metals. As it becomes more expensive to extract metals from the ground, our scrap heaps will become ‘urban mines’. Even now, researchers are working on methods to extract and reuse essential metals from waste.

Toxic minerals

We’ve long known the toxic nature of some minerals. We’ve used some, accordingly, in insecticides, to make radioactive weapons or as a means of murder. Others we avoided. But there have been those whose dangerous potential was not known until too late.

Lead

Lead, easily extracted from ores such as galena, has been used since antiquity in cosmetics, plumbing and roofing and as a food and drink preservative and colourant. More recently, it was used in paint until the 1970s and in petrol until the 1990s. Unfortunately, lead accumulates in the body and causes damage to many tissues and organs, including the brain.

Asbestos

Asbestos was used in buildings as it absorbs sound and is resistant to heat, fire and electricity. Its use was banned in the 1990s after it was discovered inhalation of fibres caused serious illness and death. Blue asbestos (crocidolite) is one of the world’s most dangerous minerals – its mining in the Pilbara region of Western Australia between 1943 and 1966 led to the deaths of over 1000 miners and residents and inspired the song Blue Sky Mine by Australian band Midnight Oil.

Arsenic

Arsenic has long been a favoured murder ‘weapon’ as it forms an almost tasteless powder and symptoms were often misdiagnosed. It has also been an accidental killer (200 people were poisoned in Bradfield in England in 1858 by sweets made with arsenic powder instead of a sugar-substitute) and a pesticide. Today, more than 100 million people worldwide have been poisoned by drinking groundwater containing naturally occurring arsenic.

Mercury

The expression ‘mad as a hatter’ dates from when mercury was used to make felt hats. Workers were exposed to high levels of mercury, which damaged their brains and caused behavioural changes. While pure mercury is not particularly dangerous, mercury compounds such as cinnabar (used since Roman times to produce red and orange pigments) are toxic. Today, most mercury exposure to humans occurs from eating fish contaminated by pollutants.

Learn more about minerals and climate change

-

Earth science

Shaping the Earth

Minerals

Fossils -

Climate change

What are we doing?

What is climate change? -

Climate change solutions

Technological solutions

Natural and community solutions