The Australian Museum Minerals Gallery

The Australian Museum Minerals Gallery is a brilliant showcase of the full breadth of the Australian Museum’s collections in the Earth Sciences.

Collecting minerals

Before museums as we now know them came into existence, European aristocrats in the 1600s to 1800s assembled natural history specimens in ‘Cabinets of Curiosities’. Such collections were eclectic assemblages – a crystallised mineral may be next to a colourful butterfly or an iridescent beetle.

Although many used these collections merely as status symbols, others studied the specimens seriously and became experts in their field. These specimens were later donated or sold to governments and became the nuclei of museum and university collections. So the era of the ‘gentleman scientist’ and private collector began and was transformed into the beginnings of the great public collections of the world.

Museum mineral collections in cities such as London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, Prague, Budapest and Madrid began in this way. In the 19th century era of scientific curiosity, it was natural that such establishments were started in overseas colonies too, so the Australian Museum was set up by a British Act of Parliament in 1827.

The Australian Museum has collected Australian and overseas minerals, rocks, meteorites and tektites since its inception and has always considered them an important part of its natural history collections.

In the 19th century especially, curiosity about plants and animals and how they were related to each other led to extensions of the original Linnean classification scheme. This system of classification into groups with similar characteristics was also extended to minerals. Minerals too were originally given Latin binomial nomenclature, but this changed quickly to the current scheme, with many species names ending in -ite or -lite, from the Greek lithos, meaning rock or stone.

Many mineral names are based on some chemical or physical characteristic, which is helpful, but others are named after people or places or even countries, which give no clues about the actual nature of the mineral. Some mineral names go back thousands of years to ancient Persian, Sanskrit or Arabic origins.

Rembrandts of the mineral world

The Australian Museum Minerals Gallery displays over 1,800 icons of our collection in a manner that brings them to life, both visually and contextually. Minerals conveys the beauty of gemstones, the wonder of meteorites, the fragility of crocoite, the weight of lead and the usefulness of ores.

It tells a story of processes and formation, that our Earth is dynamic, with minerals and rocks constantly being created, transformed and destroyed. Humans also make minerals and we feature some synthetic creations in contrast to nature’s exquisite examples.

Minerals can be experienced on many levels, and you don’t have to be a trained mineralogist to appreciate them. Everyone has had some contact with rocks and minerals, even if they don’t think they have. Many people have picked up a pretty rock on a beach or a strange stone found in the bush or have admired a colourful gem. This is certainly true because the Australian Museum receives many such enquiries every year requesting information or identifications.

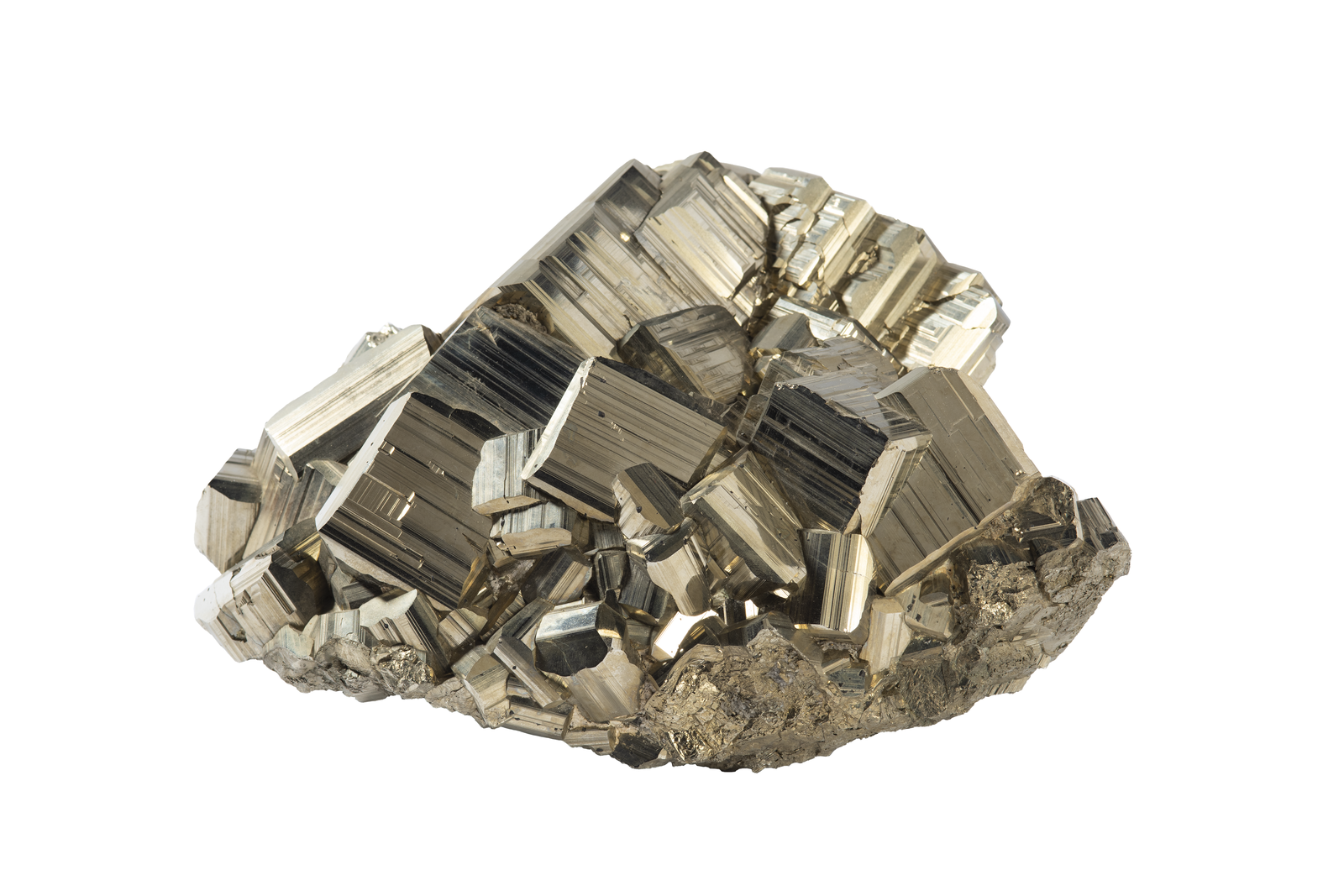

Minerals can be appreciated because of their rarity, perfection, beauty, bright colours, interesting crystal shapes and pleasing symmetry. When all of these properties come together we have something very special, a masterpiece which can take pride of place in a museum collection. The top echelons of these specimens from all over the world are unique, and they have a history or provenance which can be traced from one owner or museum to another – just like old master paintings. In fact, you can think of these as the Rembrandts of the mineral world. They are irreplaceable parts of our natural history and mining heritage, saved for posterity.

Curation themes

The minerals selected in the Australian Museum Minerals Gallery play a role in the larger narrative of the exhibition. Starting from the very beginning, we explore the building blocks of our planet – from elements, to minerals, to rocks and how scientists classify and identify them.

From there, the story moves to processes of formation. Our Earth is dynamic, with minerals and rocks constantly being created, transformed and destroyed. Humans also make minerals, and we feature some synthetic creations in contrast to nature’s exquisite examples.

'Survivors’ from deep time' explores Earth’s oldest rocks and minerals and what they reveal about our planet’s earliest days. These very rare pieces are the only traces of Earth’s first crust, long since destroyed. Other ancient survivors are meteorites and comets, formed at the birth of our solar system and drawn to Earth by gravity. Scientists study them to reveal the secrets of our solar system and our own planet.

Perhaps the most relevant theme today explores the many ways we use minerals to make our lives wealthier, better and easier.

Our ability to extract and use minerals is unique among all species, but this natural wealth has come at a cost to the environment.

Reducing our impact is becoming a priority at global and local levels and some minerals are now used in technologies that are making Earth a greener and cleaner place. The exhibition also explores these technological applications of minerals, as we never know which mineral will be the key to the next burst of innovation.