Australian Museum Research Institute

Learn about the work the Australian Museum Research Institute (AMRI) has undertaken on the impact of climate change on biodiversity, pest species detection, and effective biodiversity conservation.

When an ancient amphibian fossil met a 12-year-old Palaeo-fan

Lachlan Hart, Technical Officer, Palaeontology, Australian Museum; and PhD Candidate, University of New South Wales.

Arenaerpeton supinatus was a predatory amphibian that lived more than 240 million years ago — the fossil of which a landscaper found while he was building a retaining wall in 1996. A few months later, this impressive fossil inspired me, a budding 12-year-old palaeontologist. I now work at the Australian Museum and have formally described the species.

In October 1996, landscaper David King was building a garden retaining wall for the chicken farmer Mihail Mihailidis on the New South Wales Central Coast. At the end of the job, King hosed down the freshly laid stones, which had been obtained from Kincumber Quarry. As he cleaned off the top layer, he was astonished to find a 240-million-year-old fossil emerge from beneath the dirt.

King alerted Mihailidis, who contacted the Australian Museum about the fossil a few months later, in early 1997. Australian-based palaeontologists Dr Alex Ritchie, Dr Anne Warren and Robert Jones observed the find, as did the Canadian palaeontologist Dr Stephen Godfrey, who happened to be working on the Dinosaur World Tour exhibition in Sydney at the time. Dr Warren identified the fossil as belonging to a temnospondyl, a group of extinct amphibians that look a little bit like a cross between a crocodile and a giant salamander.

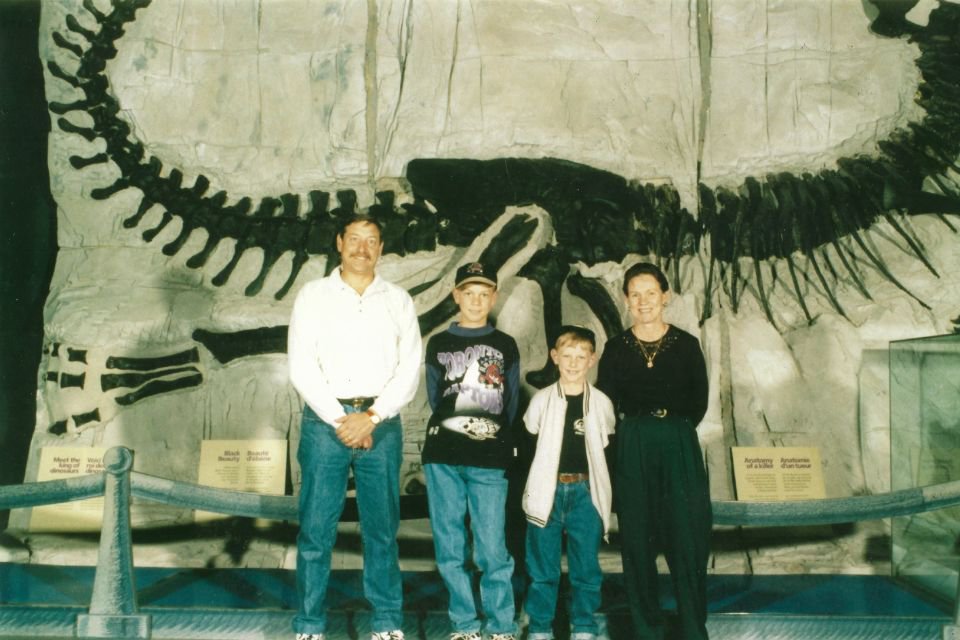

The fossil discovery caused quite the media stir, and such was the excitement that Dr Godfrey agreed to temporarily include it in the Dinosaur World Tour exhibition for the Australian public to see for the first time. It was then that I, a 12-year-old palaeontology-obsessed kid, saw it too. Mihailidis generously donated the fossil to the Australian Museum in 2000, where it has been carefully stored, waiting for a researcher with the time and expertise required to accurately describe it. Twenty years after the donation, I was offered the opportunity to work with this fossil as part of my PhD, and that description has recently been published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The fossil is undeniably remarkable. It not only has the skull of the animal still attached to the skeleton, but it also contains the impressions of the animal’s soft tissue (skin) around the body. The skeleton is missing the tail and back legs and is preserved belly-up, so we can’t see features of the top of the skull, such as sutures between bones and eye sockets, which are usually very helpful in identifying species.

After comparing it to many other temnospondyl amphibians, I discovered that it was indeed a new genus and species, which I have named Arenaerpeton supinatus (pronounced Ah-ree-nah-er-pet-on / soo-pin-ah-tus). “Arena” means “sand”, and “erpeton” means “thing that creeps” in Latin. This is a reference to the sandstone block in which it lies and the fact that it was an amphibian that was probably doing its fair share of creeping around. “Supinatus” translates to “supine”, or “lying on its back”, which is how the animal is preserved. So, the name therefore means “supine sand creeper”.

Through studying Arenaerpeton, I have learnt a tremendous amount about temnospondyl amphibians. Temnospondyls are an important case study in the fossil record, as they survived two of Earth’s Big Five mass extinction events, including the Great Dying at the end of the Permian period, which wiped out more than 80 per cent of all living things. Arenaerpeton belongs to a group of temnospondyls called chigutisaurids, which also contains the last-ever temnospondyl, Koolasuchus cleelandi, from Victoria. Koolasuchus was enormous, perhaps up to five metres long. Arenaerpeton, while not so big (probably about 1.2-1.5 metres long), was still quite large for its time, as other chigutisaurids that lived during the early-middle part of the Triassic period were smaller. This shows that this amazing group of survivors was already starting to evolve into large sizes not long after the most catastrophic extinction event in Earth’s history.

Arenaerpeton supinatus is a key part of Australia’s fossil heritage. Not only is it a unique fossil with incredible preservation that adds a vital data point in understanding the evolution of vertebrates in Australia but it also holds a treasured place in the memories of many who recall its discovery. This is highlighted by my connection with this fossil, from seeing it as a child to being lucky enough to work on it for my PhD.

Perhaps one day, another kid like me will see it at the Australian Museum and be as inspired as I was.

Gobsmacking goby fish species found in museums

Dr Yi-Kai Tea, Chadwick Biodiversity Research Fellow, Ichthyology, Australian Museum.

An exquisite new species of goby has just been described – and it was found in a museum! A new publication co-authored by Dr Yi-Kai Tea, the Australian Museum’s Chadwick Biodiversity Research Fellow, describes these showstopping fishes and highlights the importance of taxonomic research in museums.

Describing a species new to science is certainly an exciting endeavour, but what many may not realise is that scientists sometimes describe a new species without collecting any new material. This was the case in the newly published study by the Australian Museum’s Chadwick Biodiversity Research Fellow Dr Yi-Kai Tea, and Dr Helen Larson. The authors revised the taxonomy of a species of dartfish belonging to the goby genus Nemateleotris. The species, Nemateleotris helfrichi, is one of only four in this genus. They soon realised, however, that what was known as N. helfrichi was actually two species of fishes that differed in aspects of colouration, size and geographical distribution. What’s more, is that the study was borne entirely out of examining existing specimens housed in museums.

Careful examination of international museum material and comparison of live underwater photographs revealed the presence of two distinct species living in non-overlapping parts of the world. Nemateleotris helfrichi is restricted to the islands of French Polynesia, and the newly described species, N. lavandula, occurs elsewhere in the western and central Pacific. Both species are most easily separated in colouration details of the head and snout. Notably, the ‘moustached’ N. helfrichi has a distinct black mark on its upper jaw, which is absent in N. lavandula.

Strangely, for a fish that is so widespread and popular as an aquarium pet, the goby is very poorly represented in museums. The new species is described based on only 13 specimens that are scattered across museums in Australia, the United States, Japan and Singapore. The holotype was selected from a specimen housed right here at the Australian Museum and is extra special because it now holds two type statuses — the other being the paratype of N. helfrichi.

The description of the new species accompanies a revision of the genus Nemateleotris, with new accounts of osteology, re-diagnosis of all species, and a revised key to species. This study by Dr Tea and Dr Larson is an excellent example of how revisiting historical taxonomic descriptions with fresh eyes can have a direct impact on conservation and species management. In this case, one species, previously thought to be widespread, has been found to harbour cryptic diversity, leading to the understanding that the newly described species is restricted to a much smaller distribution than previously known.

Expedition: The explorers

As the first phase of the Australian Museum’s Norfolk Island expedition closes and the second begins, our experts reflect on their findings.

Expeditions are at the heart of what natural history museums are all about. They are an opportunity to collect specimens, describe new species and study the incredible biodiversity of this planet – expeditions provide us with a snapshot of how our biodiversity is tracking, and how we can conserve it.

Located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, about 1700 kilometres northeast of Sydney, Norfolk Island is a small island with a diverse array of birds, insects, reptiles and marine life, many of which are unique to the island. It also has notable historic sites offering a unique heritage seldom found elsewhere around the world.

It is also largely underrepresented in the Australian Museum’s collections, so was the perfect location to conduct a broad-scale, multi-pronged collaborative program of biodiversity surveys and archaeological fieldwork. The AM’s Norfolk Island expedition provides an opportunity to learn more about threatened species and those new to science, to study how pest species such as invasive rodents affect the island’s biodiversity, and how we can monitor these effects in the future.

Phase one, which focused on rats, bats, cats, geckos, skinks, insects, spiders, birds, snails and plants, is complete. Phase two, due to commence soon, will focus on marine biodiversity.

The birds

From iconic Green Parrots to soaring seabirds, Norfolk Island is home to many beautiful birds – however, it also has an unenviable extinction rate.

Australian Museum scientists Emily Cave and Dr Richard Major collected data from both native and introduced species, including collecting genetic samples from native birds. Before dawn each morning for a week, Cave and Major hung up mist-nets. These nets are nearly invisible to the naked eye – and sometimes invisible to birds. Designed to catch birds without harming them, various species were captured in these nets, enabling scientists to take their measurements, sample their feathers and blood and take photographs. The bird would then be released, without harm, back into the wild.

All specimens and samples taken provide researchers with material for ongoing studies of taxonomy, phylogeography (genetic relationships across geography) and the evolution of island faunas. The AM holds bird specimens collected on Norfolk Island from the 1880s to the 1990s, but the most recent period of sustained research activity was in the late 1960s and 1970s. Historically, most specimens in the AM collection from Norfolk Island were of eggs, with only one tissue sample and one skeleton specimen represented. Therefore, all specimens acquired during the expedition are highly significant: the collection now has contemporary specimens of various forms and an increased representation of the island's bird fauna.

- 32 individuals of eight native species were sampled from mist-nets, including the Warbler, Robin, Golden Whistler, Grey Fantail, Long-Billed White-Eye, Green Parrot, the Australian Silvereye and the Pacific Emerald Dove.

- Samples of the Australasian Swamphen, Welcome Swallow, Sacred Kingfisher, Masked Woodswallow, Nankeen Kestrel, White-faced Heron and the Pacific Golden Plover were received as donations.

- 11 species of introduced bird were sampled, including the Feral Chicken, Mallard Hybrid, California Quail, European Blackbird, Song Thrush, Goldfinch, Greenfinch, House Sparrow, Rock Dove, Crimson Rosella and the European Starling.

The plants

A team from the Australian Institute of Botanical Science collected about 400 plant specimens, helping the community identify new weeds that potentially could cause havoc to local ecosystems.

The Institute team’s mission was to collect herbarium specimens to help fill knowledge gaps of Norfolk Island’s flora, focusing on areas where no or few collections have been lodged in Australasian herbaria. (Herbarium collections provide permanent records of plants and where they were growing. They are invaluable resources, physically and electronically, that are available to the community and researchers from around the world.)

In addition to herbarium material, the team collected tissue samples for DNA extraction and analysis for future projects. All material, including tissue samples, will also be digitised to make them available to researchers internationally.

The Norfolk Island pine tree is an iconic species from the island.

Image: Tom Bannigan © Australian MuseumSenior Botanist Marco Duretto said as well as Oxalis pes-caprae, Soliva anthemifolia (Button Burweed) and Hypochaeris albiflora (White Flatweed) were provided to the team by locals and are new records for Norfolk Island. A new species of fern in the genus Blechnum was also a significant find, and may represent a new, possibly naturalised, species for the island.

“This Oxalis weed is a real scary one — it’s a spectacular species and beautiful to look at — but it has underground bulbs and is a very serious weed. Once it gets into local areas, it’s hard to get rid of. It forms monocultures because other things that live on the ground next to them get excluded," Duretto said.

Honorary Research Associate Matt Renner collected bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts), which significantly expanded the knowledge of the bryophyte flora of the region, with first records of families, genera, and species for the region commonplace.

All up, the team made c. 400 collections (including 160 bryophytes) of c. 140 species and the numbers of species will increase as identifications are finalised, especially that of the bryophytes.

The insects and spiders

The insects and spiders of Norfolk Island and Phillip Island are incompletely known. The ongoing identification of insect and spider specimens is throwing up many new family and species records and plenty of puzzles.

The team collected a variety of spiders and targeted certain groups of insects, specifically plant-feeding beetles. The techniques used included hand searching (looking beneath woody debris, night collecting), sifting dirt litter over a tray, knocking animals off vegetation into a tray (a technique called beating) and setting overnight traps on the ground.

The Norfolk Island region has faunal and floral biogeographic links with Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia, not to mention the potential for human introductions over many years of settlement. As a result, it is often impossible for the team to be sure of the status of a species they find: is it a unique endemic species that occurs nowhere else in the world, or is it a poorly known or unidentified species that is actually quite widespread? If the latter, then is it native to the island, or have people brought it here?

Dr Helen Smith and Natalie Tees looking for insects and spiders on Norfolk Island.

Image: Tom Bannigan © Australian MuseumIsland ecosystems are constantly evolving, and the addition of new species, which are often effective colonisers, can be a disaster for locally evolved endemic species. The new arrivals may be adaptable and/or aggressive, they may take over habitats or even directly feed on the native species. To enable effective conservation, it is vital to take stock of the situation, which means trying to identify all our specimens as far as possible.

AM’s beetle expert, Dr Chris Reid, examined the Coleoptera and reported 69 species, including seven longhorn beetles (Cerambycidae), seven leaf beetles (Chrysomelidae) and 29 weevils (Curculionidae) – these were the plant-feeding target groups and several of these species are undescribed. The most interesting beetle capture was a new flightless species of Phanodesta (Trogossittidae) – a genus previously only known from New Zealand, Lord Howe Island and the Juan Fernández Islands off the coast of Chile.

Among the spiders, almost 60 species have been separated and identified as far as possible. Some exciting finds include spiders from nine families that had never been recorded in the Norfolk Island region before 2022. The conservation status for most of the nine is unclear.

The rats, bats and cats

Historically, when scientists have surveyed an area, they have tended to focus on native species rather than invasive species. As a result, very few samples of introduced populations are represented in museum collections.

In terms of mammal diversity, the fauna of Norfolk Island is dominated by introduced species, including feral cats (Felis catus), house mice (Mus musculus), black rats (Rattus rattus) and Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans). As Norfolk Island is a volcanic island, native mammal species are limited — mammals not being great over-water dispersers unless they can fly. For this reason, only bats have naturally found their way to Norfolk Island, but humans have introduced a range of mammal species.

The AM’s mammalogy team — Dr Mark Eldridge, Dr Sandy Ingleby and Professor Kristofer Helgen — had two aims during the Norfolk Island expedition. The first was to identify whether the island's only native mammal, the Gould’s Wattled-bat (Chalinolobus gouldii), still resides on the Island. This bat has not been officially recorded on Norfolk Island for more than 20 years. The team deployed ultrasonic bat detectors at 34 sites across Norfolk Island and two on neighbouring Phillip Island. In addition to the 90,000 sound files recovered from the detectors, the team gathered sighting information from local residents. Despite these efforts, no bat calls were detected during the survey.

The second aim was to collect samples of the introduced mammal species on the Island. All of these species have had a significant impact on the Island’s biodiversity, so it’s important to understand them and document their presence. The team set out Elliot and cage traps in remnant native vegetation and around buildings to document what invasive species were present, and to collect high-quality genetic data.

There is increasing global interest in documenting introduced species because they tend to parallel human movement and history, as humans introduced them. In the case of Norfolk Island, the Polynesian rat was introduced about 500 years ago with Polynesian settlement; house mice were introduced with convict settlement in 1788; and during WWII or perhaps earlier, the black rat appeared. Each of these introductions has had a major effect on the native flora and fauna, and each has an interesting history in terms of human movement around the globe.

As invasive species are poorly represented in museum collections, there are few to no tissue samples available for genetic studies. Collecting these specimens has filled a significant gap in global museum collections and has provided material for future studies.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Polynesian/Tupuna/Tipuna who first called Norfolk Island home, whose story is still being written and pieced together. Through our work, we endeavour to add pages to their widely unknown narrative. We honour their connection to this land/whenua and fauna in times gone by and invite them to guide and breathe life back into the treasures which they left for us to uncover and to piece together the story they did not tell.

We extend that acknowledgement to the descendants of the Pitcairn Islanders who still walk this land and whose Polynesian ties link them back to the East of this Great Ocean — Tahiti. We honour their Pacific story on this land, we acknowledge their Tupuna/Tipuna ancestors and the culture they forged here on Norfolk Island. A culture that continues to thrive today.

And finally, we acknowledge the other Pacific Island communities that now call this Island home. The Pacific diasporas from across the Great Ocean — whose connection to this land may be more recent but whose presence also adds to the Pacific narrative of Norfolk Island in the here and now.

Celebrating 50 years of research on Lizard Island

In 2023, the Australian Museum celebrates 50 years of research on Lizard Island Research Station and vital work on reef ecologies and the impacts of climate change.

Founded in 1973 by former AM Director, Professor Frank Talbot AM, the Australian Museum's Lizard Island Research Station (LIRS) has studied reef ecologies and the impacts of climate change for 50 years. In such an isolated place, dedication to research on the reef becomes a lifestyle, and fieldwork is ongoing — through rain, hail or shine.

This year, we celebrated 50 years of the AM’s LIRS, a globally recognised research station devoted to understanding the incredible scale and structure of the Great Barrier Reef, which can be seen from space.

From humble beginnings on a remote island, building the facility from the ground up, to a hub of internationally renowned research and climate change action, the researchers at Lizard Island Research Station challenge us to contribute to climate action and become custodians of the lands we live on.

Thousands of international marine scientists have been trained on or conducted valuable research on Lizard Island. About 100 research projects are annually conducted by some 400 scientists and support personnel. What a place to discover and learn!

In the past half-century, 2700 scientific publications have been produced from work conducted at LIRS, with film crews regularly using it as a base for quality climate engagement documentaries, opening minds with arresting visuals that move us to act.

A lifetime of achievement

Dr Anne Hoggett AM and her partner, Dr Lyle Vail AM, have been at the forefront of important research conducted on Lizard Island since 1990. In October, they were awarded the 2023 Australian Museum Research Institute Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of their tireless work in advancing our understanding of coral reef biology.

Dr Hoggett was our esteemed speaker for LIRS at this year’s Talbot Oration: Coral Reefs in Hot Water, in May. “Australia is in a unique position as custodians of the largest Reef system on Earth,” she said. “We have committed to the world that we will look after them and we're a rich nation with strong scientific expertise and untapped opportunity to reap the rewards of a renewables revolution so if not us then who?”