Prehistoric Australia

Australia's prehistoric history reveals dramatic transformations in ancient landscapes and extinct species that shaped today's unique biodiversity. From megafauna to ancient marine life, discover the extraordinary animals that lived in prehistoric Australia millions of years ago.

Our ancient past

Australia's ancient past shaped the extraordinary biodiversity we see today. Around 33 million years ago, Australia finally broke away from Antarctica, its last Gondwanan link, and began drifting in isolation. This separation enabled a unique evolutionary path, giving rise to remarkable creatures and landscapes found nowhere else – fanged kangaroos, strange monotremes, towering eucalypt forests and megafauna like giant wombats and huge lizards.

Follow Australia through the ages with the interactive below and see how drifting continents shaped our of remarkable biodiversity.

Australia’s isolation

The Early Miocene: 23 to 16 million years ago

By the Early Miocene, Australia had completely spilt from Gondwana and had become an island. Isolated from the rest of the world, animals began to evolve in ways seen nowhere else. This was a time of booming diversity and evolutionary experimentation.

Lush rainforests were home to distant ancestors of animals that populate Australia today. But others were far less familiar – like giant flightless birds and marsupial predators.

Step back into the Early Miocene with the interactive below and uncover the extraordinary animals that lived in Australia’s ancient landscapes.

Rainforest roos

The earliest known kangaroos were small, ground-dwelling marsupials that bounded through the fallen branches of Australia’s ancient rainforests. They were more like tree-scrambling possums than the hopping kangaroos we see today.

Meet the first kangaroos

Ekaltadeta ima

Ekaltadeta was part of an early lineage of kangaroo experimentation. Like most early kangaroos, it likely had strong arms and bounded on all fours. It was also probably a decent climber. Ekaltadeta had a very large, serrated premolar tooth, useful for cutting tough materials like insect carapaces, fungi and flesh.

Balbaroo fangaroo

Balbaroo fangaroo was a not-so-distant relative of Ekaltadeta. It had long, curved canine teeth, probably used to fight over resources and territory. These would have been particularly feisty ‘roos.

Drying of Australia

The Late Miocene - Pliocene: 11.6 to 2.6 million years ago

By the Late Miocene, Australia's lush rainforests had shrunk as the climate became cooler and drier. Open canopy forests dominated by plants like eucalypts expanded, and grasslands spread across the continent.

During the Early Pliocene, the Australia we know today was emerging. Like today, the forests were dominated by gum and wattle trees. As the land continued to dry, grasslands expanded and wildflowers bloomed into new open spaces. Familiar animals like Budgerigars and Saltwater Crocodiles started to appear.

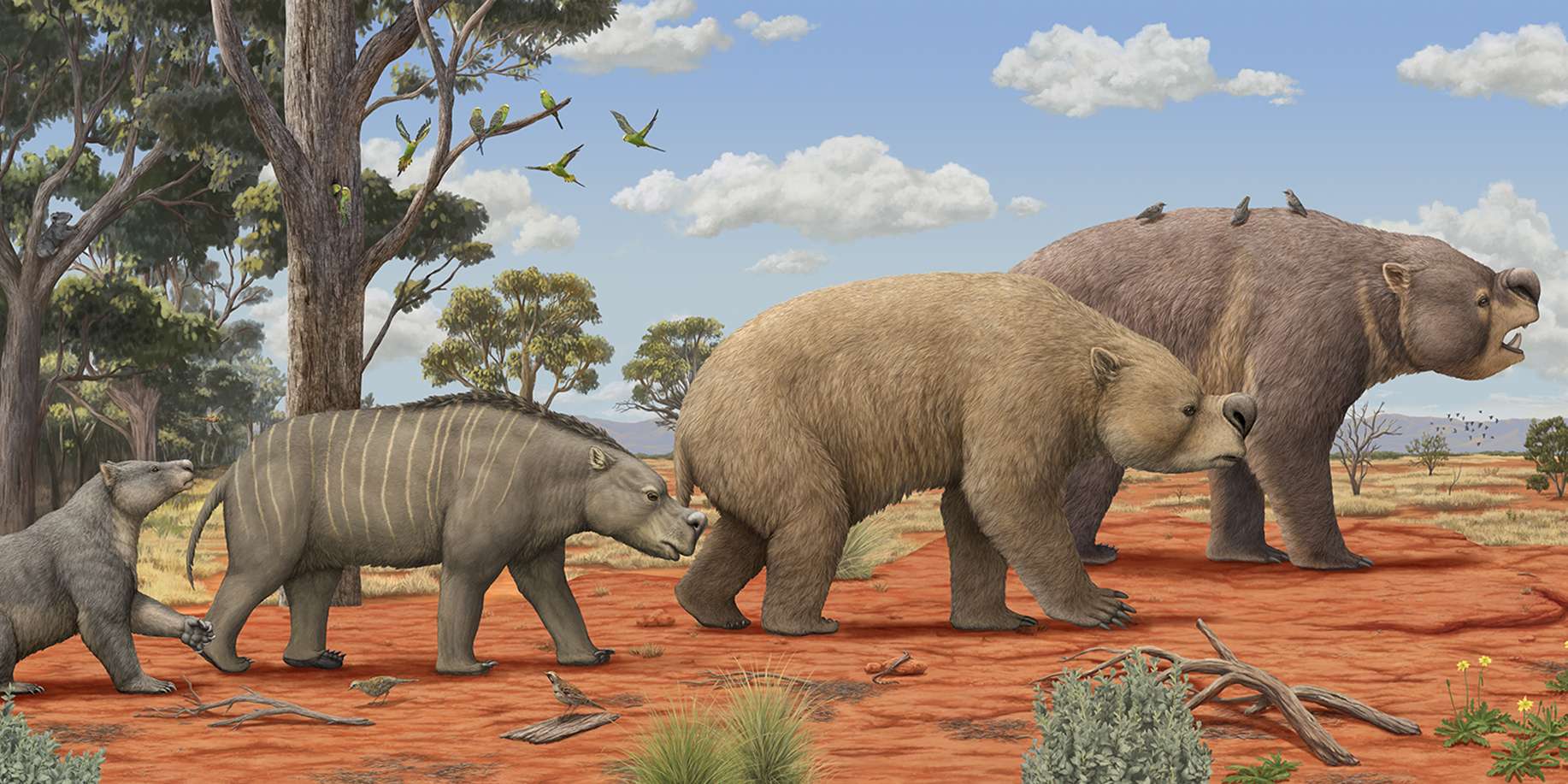

As the environment changed, animals changed, too. The diprotodontids, once tree-climbing creatures, started to explore the wide, open spaces. Over time they became specialised giants. They evolved to become bigger and stronger which was ideal for walking long distances.

Explore the interactive below to see how changing landscapes shaped remarkable animal adaptations, giving rise to both giants and familiar species.

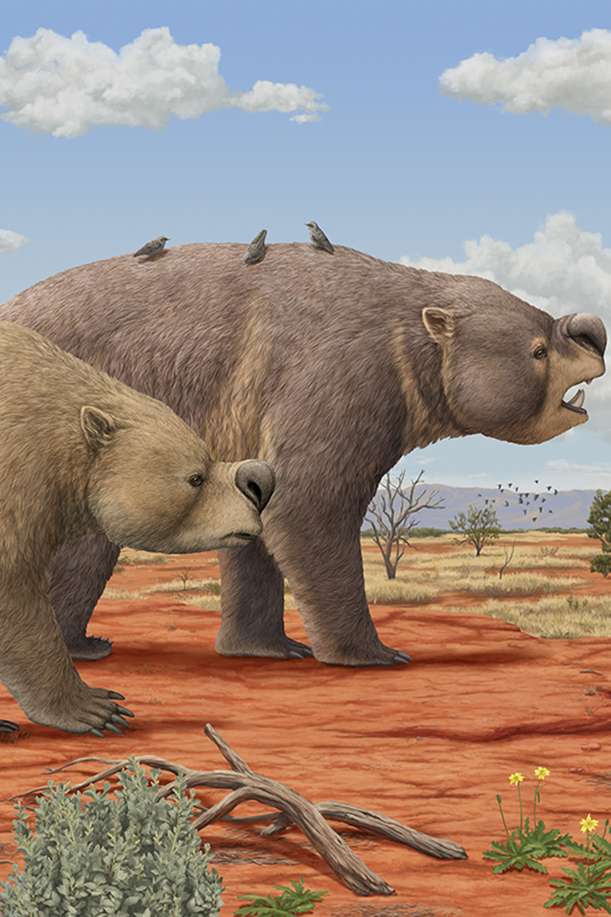

The mighty Diprotodon

Diprotodon optatum was by far the largest marsupial that ever lived, and the heaviest of Australia’s megafauna, weighing up to 2700 kilograms. It was a giant specialised for walking – its long and columnar legs with stout feet helped this massive animal roam far and wide in search of shrubs and trees on which to browse. It may look a lot like a giant wombat but it’s not. While it is a relative of today’s wombats and Koalas, it belongs to an extinct family, the diprotodontids.

Time of giants

Pleistocene: 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago

Australia’s modern land animals aren’t all that big. There are no elephants, hippos or big cats. But the fossil record tells a different story: Australia’s animals included giants.

During the late Pleistocene, as the climate turned cooler and drier, the great interior deserts started to form, sea levels fell and grasslands spread. In response, some animals evolved into true titans: giant wombats, towering kangaroos, massive monitor lizards and fearsome pouched predators.

These ‘megafauna’ once ruled the continent. Today, we can only imagine what it would be like if they still roamed Australia.

Meet the megafauna

Carnivorous marsupial

Thylacoleo carnifex

Thylacoleo carnifex was the largest marsupial predator known, weighing over 120 kilograms. With opposable thumbs and large curved claws, it was built for power. Thylacoleo had strong arms to grip prey and specialised teeth that sliced through flesh. Its short-snouted skull delivered an incredibly powerful bite – perfect for taking down large animals.

Giant wombat

Phascolonus gigas

Phascolonus was a true giant, likely weighing over 500 kilograms. It had huge strap-like teeth and strong arms which helped it dig for food. The top of the skull was dish-shaped and may have supported a rough callous or fatty pad. Perhaps they head-butted and shoved each other in fights over resources.

Armoured predator

Megalania, Varanus priscus

In the time of marsupial giants, the largest terrestrial predator was a reptile. Megalania was a gigantic monitor lizard over five metres long and around 300 kilograms in weight. It had a heavy skull and curved, serrated teeth used to rip and tear through flesh. The head and neck had small bones embedded in the skin called osteoderms. These bones acted like chainmail armour, presumably for protection during rough-and-tumble fights over resources.

Giant marsupial mystery

Palorchestes azael

Palorchestes was unusual. This giant marsupial weighed around 1000 kilograms. It had a tall and narrow skull with tiny eyes, scoop-shaped front teeth, and possibly a long, flexible tongue. Retracted nasal bones and large facial nerves point to a sensitive, mobile snout. Did it have a trunk, a big fleshy nose or prehensile lips?

Short-faced king

Giant Short-faced Kangaroo, Procoptodon goliah

Meet one of the largest kangaroos of all time – Procoptodon goliah weighed over 250 kilograms. Its short face wasn’t the only odd thing about it; it also had long arms with long claws on its hands, and only one toe on each foot. Its feet and hips suggest it walked on two legs instead of hopped, and footprint evidence records them doing so.

Prehistoric brawler

Lord Howe Island Horned Turtle, Meiolania platyceps

This turtle was a prehistoric brawler. Only found on Lord Howe Island, it had horns, a tail club and a shell about a metre long. These giants were like ‘turtle-tanks’. They likely head-butted and tail-whacked rivals when fighting over resources.

The great extinction

In a wave of rolling extinctions that affected megafauna all over the world, an incredible 86 per cent of Australia’s giant land animals had disappeared by the end of the Pleistocene, 11,800 years ago. The event was so dramatic it’s referred to as ‘the Late Pleistocene megafauna extinction’.

The arguments about why they died have raged since the first megafauna fossils were discovered. There is a range of possibilities, but it is most likely related to climate change and human impact.

Australia’s fossil sites: clues to the past

McGraths Flat fossil site

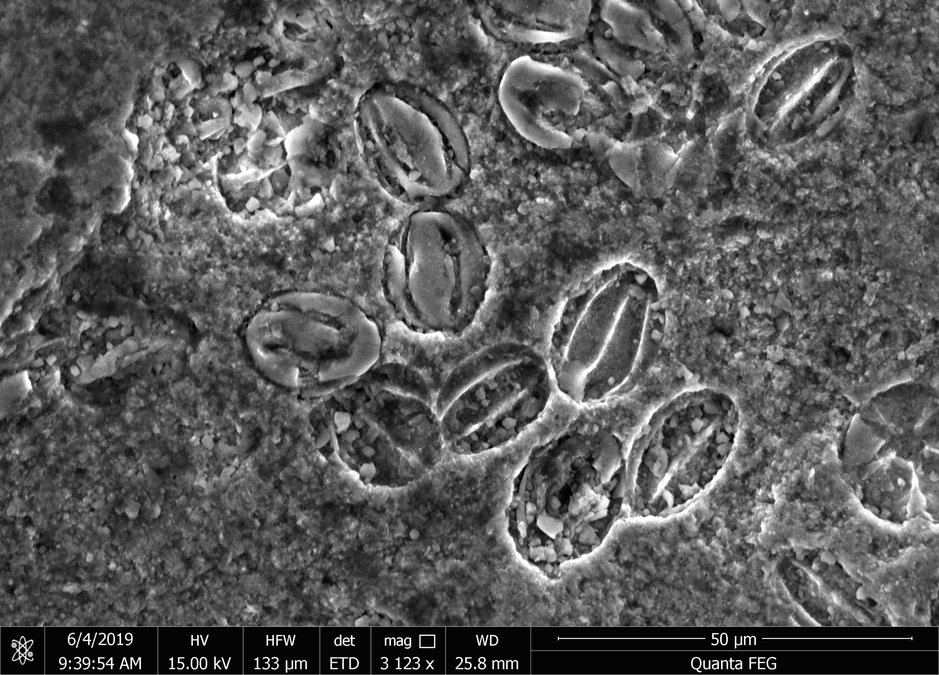

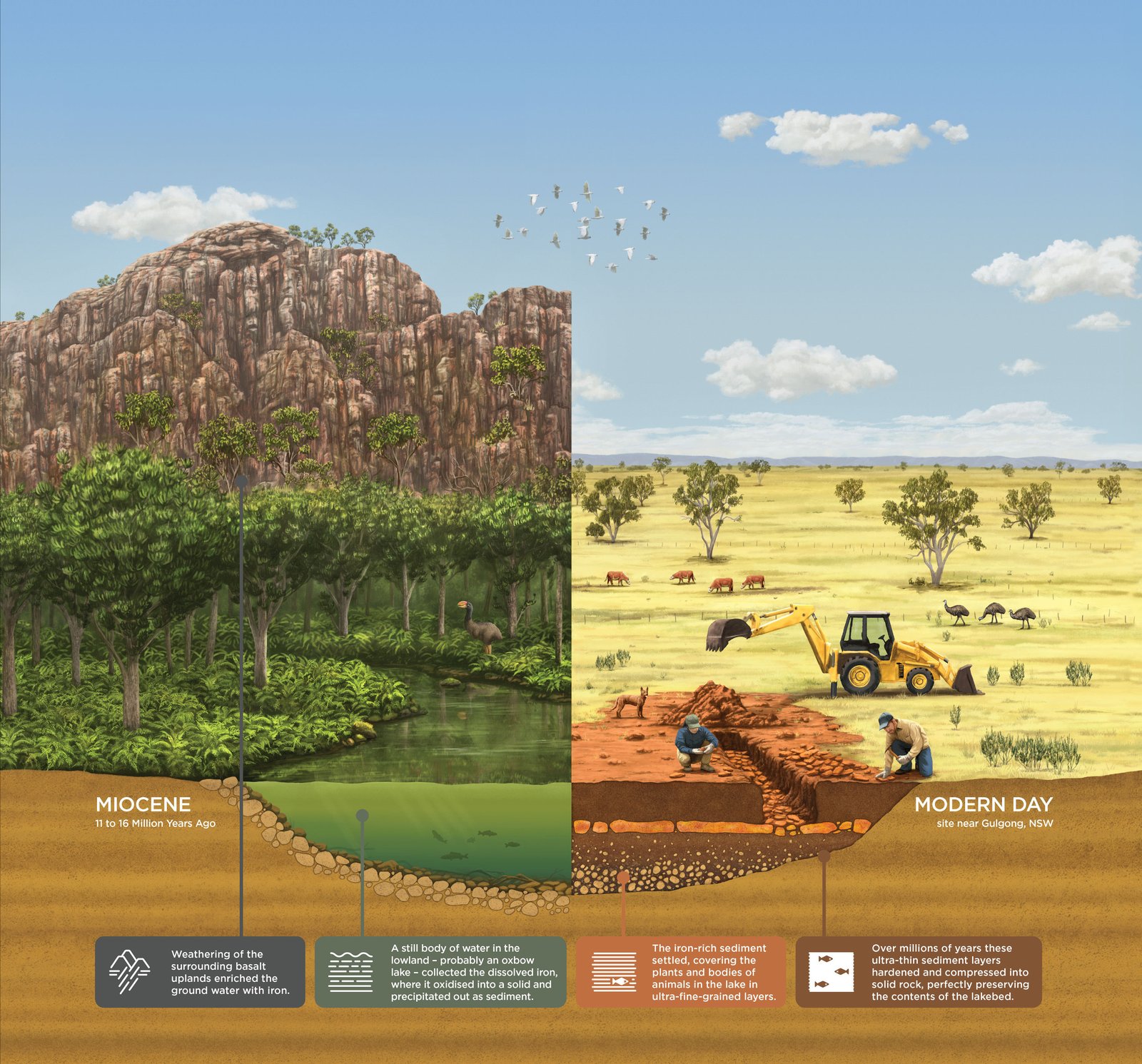

An exceptional, recently discovered site is McGraths Flat in New South Wales. This site is a Konservat-Lagerstätte, or a fossil site known for exceptional preservation. Fossils here have been preserved down to the microscopic level and include plants, insects and fish from around 16 to 11 million years ago. These fossils show us what the environment was like in the past and how ecosystems change over time.

The site was identified by a local farmer and is now researched by the Australian Museum’s palaeontology team who continue to discover new species.

McGraths Flat provides a rare window into what Australia was like in the Miocene. At this time Australia was in the process of becoming more arid, and so it gives us a picture of what ecosystems were like during this time of immense change.

How was the McGraths Flat fossil site formed?

Fossil of Baladi warru

The incredible preservation at McGraths Flat offers rare glimpses into relationships between species and their environments. This fossil sawfly still carries pollen grains from a plant called Quintiniapollis psilatospora on its head. Like many sawflies today, Baladi warru was a pollinator.